A Color Theory Reading of Jane Campion’s ‘In the Cut’

In our new column Color Code, Luke Hicks chooses a handful of shots from a favorite film in order to draw out the meaning behind color and how it plays into both the scene and the film as a whole. For his third entry, he analyzes Jane Campion’s In the Cut.

“She didn’t care what happened, as long as it wasn’t coy,” Meg Ryan explained during the In the Cut press tour in 2003. Ryan was referring to Jane Campion, the stalwart of frank cinematic expression and the writer and director of the film, a salacious, pitch-dark romance that is anything but coy. On the contrary, Campion’s explicit, boundary-shattering examination of eroticism through the female psyche does everything in its power to disarticulate the swooning Hollywood notion of love.

Frannie Avery exists on the opposite end of the spectrum from the quintessential Meg Ryan rom-com role. Critical, sharp, disaffected, and quietly impassioned, the character works as a creative writing professor in Manhattan. She and her overly experienced half-sister Pauline (Jennifer Jason Leigh) are single, weathered, middle-aged women estranged from the Western mythology of romance, in which a strapping man is supposed to sweep them off their feet and into a flowering, fairy-tale eternity. But their seedy reality doesn’t keep them from daydreaming about it together, and their dreaming doesn’t keep them from nightmares. After all, they live in the cut.

The day after Frannie witnesses a woman performing oral sex on a silhouetted man in the basement of a bar, a woman is found cut into pieces in the bushes outside of Frannie’s apartment. Enter: Homicide Detective Malloy (Mark Ruffalo), one of the only romantic co-leads in film history who is suspected of serial murder by the woman infatuated with him. Malloy and his filthy-mouthed cop buddies become a regular fixture in Frannie’s life due to the investigation. The two tumble into a steamy affair full of unspoken tension that grows with the discovery of more dismembered bodies.

Campion’s challenging portrayal of a woman severed from storybook love is bloody, bewildering, and beautifully shot in its impressionistic blur and looming shadow (courtesy of Dion Beebe). The opening credits alone achieve more in the expression and significance of color than most films could dream of in their runtime. I also chose In the Cut because it’s a masterclass in shading and combining colors. In particular, reds and greens — uncoincidentally creating a complementary color scheme — dominate the film with variable meaning depending on the tint and the circumstance. It is an all-time feat of cinematography (not to mention set, costume, and makeup design) and the use of color that could warrant its own color theory column. Until then, here are four shots that illustrate Campion’s interrelated use of color.

This first shot comes at the end of a relayed memory: Frannie fills her sister in on how their dad proposed to Frannie’s mom. As she begins the story, Campion sends us into a monochromatic, sepia-toned past that wears the mood and texture of an old photograph. The proposal tale itself is bizarre. Supposedly, their father was at the ice rink with his fiancé when he noticed Frannie’s mother, whom he’d never met and couldn’t take his eyes off of. Jealous as could be, his fiancé stormed off, and he skated over to Frannie’s mother to propose with the same ring. “And at that precise moment, which is the thing that my mother always added, it started to snow.”

“Very romantic,” Pauline says before whispering, “I don’t quite believe it.” They both know better. The ridiculous romance mythology represents the warped Disney-esque ideal Campion is confronting, which is elicited through the delicate, antique color, glistening white snow, and impressionistic wood in the background. Frannie and Pauline know there’s no prince charming on the horizon (for anyone, not just themselves), and they ridicule the concept on occasion, but they still lust after it with a pinch of hope. They’re psychologically plagued by having grown up in a world that taught them they needed a man to be complete.

Campion uses the sepia-toned, wood-nestled ice rink setting – soundtracked by discordant, atmospheric piano – as the foundation for Frannie’s interior longings, conjuring it whenever she drifts into a spell. The recurring fantasy ominously introduces itself, without context, in the opening credits. But by the end, it warps into an incubus in Frannie’s mind, the last bloody appearance involving her father’s ice skates and her mother’s lopped-off limbs.

“He killed her. When he left, she just went crazy with grief,” Frannie mumbles in a daze after they agree the story isn’t true and bring the memory of their father back down to Earth, or lower. Perhaps Campion is suggesting that the romantic ideal spoon-fed to young girls is more likely to get them killed, whether literally or emotionally, than taken care of. As it turns out, their father married four times, and Pauline’s mom wasn’t even one of the four.

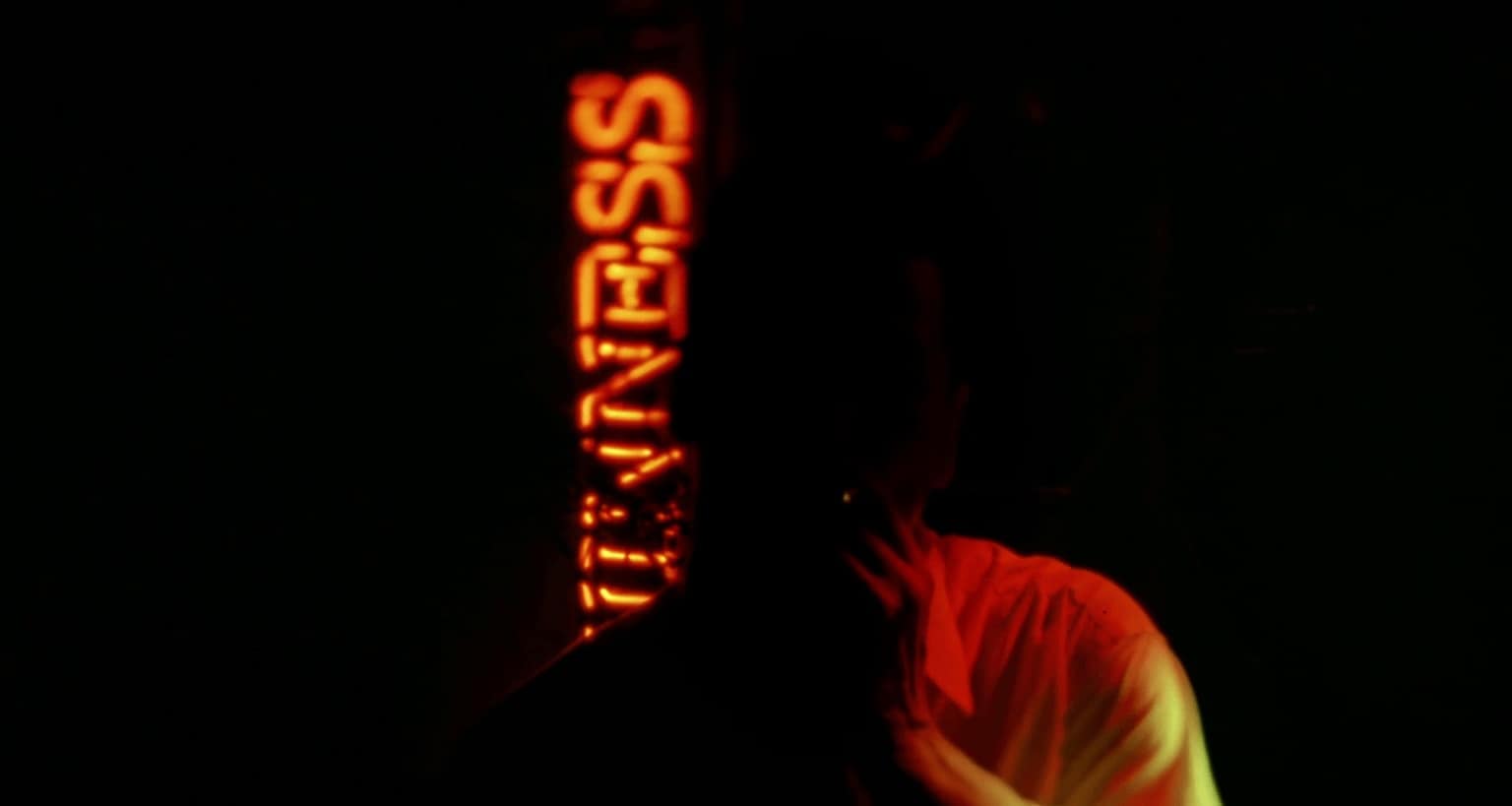

The darkness of In the Cut cannot be overstated. That goes for theme and mood, as well as cinematography. This shot is a perfect example. Here, we have the first image of the killer, swallowed in shadow so solid it could be made of concrete. His shape is outlined by the menacing red neon that flanks him from behind and creeps onto his left shoulder. The white of his Oxford button-down is obscured into a sort of sickly yellow-green, which, combined with the red, creates that persistent complementary color scheme. It’s also worth mentioning that a complementary color scheme is defined by two colors that exist on opposite sides of the color wheel from one another, the scheme being a theme in itself.

The way it’s shot makes it look as if we’re seeing through a sort of peephole. We happen upon the scene with Frannie when she descends into a dive bar basement. Below the screen, the same woman who will be found in pieces the next day is going down on the killer. Peeking out from behind a wall, Frannie watches, both bothered and aroused by her voyeurism. In context, we don’t know he’s the killer yet. We don’t even know there is a killer yet. But the camera, the color, and the darkness communicate everything we need to know.

Red is the color of extremes: violence, sex, passion, seduction, exhilaration, danger, fury, etc. Here, the red is dynamic. First, it represents evil, danger, and all things synonymous. We’re peering into a villain’s lair, but this is Campion’s version. Instead of donning a bright lightsaber, he simply wields a cigarette, barely emerging from the shadow at its ember end. He’s cool and confident in the darkness, unphased by what little light partially reveals him. That we’re unsure if he’s staring back is a testament to his control over the situation.

However, the red with the shadow is also grossly alluring in its malevolent seduction. Frannie can’t quit staring. Watching her watch is difficult to watch and even more difficult to process. One can’t watch without participating in Frannie’s voyeurism. Whether we choose to see it through her eyes or see her through our own, we’re watching. In this sense, the red also elicits passion – a strange, desperate passion that could be either sinister or sane. Love in the modern age.

Complementary shades of red and green carry this movie on their back. They do so much aesthetic and thematic heavy lifting across the film, they might as well be their own color spectrums. Here, they pop in garish fashion, their shades and shapes in tonal harmony with the revolting scene of the crime. Another woman has been found sliced up, stuffed into a laundry machine this time. Malloy is on the other side of the camera. We’re seeing through his eyes. Blood pools on the table just below his face, a clue that the killer is right under his nose.

This complementary scheme is more varied. For example, the lurid yellow-green neon number tags communicate caution and warning. However, the minty green in the back is soft. The hands that are soon to unpack the limbs from the washer are gloved in a kinder, more therapeutic color – one that communicates a solution, or healing and rehabilitation. Or, to stretch it out, perhaps it communicates a departure from the romantic models that land a woman who thought she was going on a date in pieces in a washing machine instead. Campion doesn’t just casually refer to such models as “traps.” Backward philosophies we learn as children must be actively unlearned. They don’t disappear on their own.

The sticky, erotic subterranean world of In the Cut is crawling with vile men, the finest one of whom complains about past hookups with “no sense of cock.” This man — Malloy, still the crème of the crop, mind you — descends from a line of brash blue-collar fellas whose regard for women is masturbatory at best, and while he reflects them, he also signals a critical departure in the genealogy of brutes in his sincere desire to prioritize Frannie’s pleasure in their sexual encounters.

In the film, sex and violence are undoubtedly but inexplicably linked. This is a perfectly vulgar shot to illustrate it. It jumps from Malloy staring down the horrific violence to walking Frannie through some phone sex at the ring of a cell, as if the blood and body parts he was gazing at sparked the call and fueled it with a mysterious eroticism. It didn’t, but that’s exactly why the relationship between sex and violence in this film must be wrestled with endlessly if one wants any clarity. The use of slang to undermine the meaning of a word provides a similar duality that could be interpreted in one thousand ways.

Lastly, the blood-splattered white laundry machine plays a major role in the color of the shot, too. White often represents institutions, in this case, a police department. The dismembered woman is encased in the institutional white, which foreshadows the identity of the killer as someone within the institution. Later, in the final lighthouse sequence, a wide shot displays the red phallic building where the killer takes his victims situated in darkness like a zit on the underside of the solid white bridge (institution) towering over it.

This last shot showcases the way Campion uses completely different color and lighting to express similar themes with a different bent. The phantasmic, shadowy, and gory shots above thematically exhibit danger in their own ways: romantically idealized men, doomy basements, and savage crime scenes. The use of gardens to elicit danger is more peculiar but no less effective.

In this shot, we see Frannie coming home, walking through the garden we’ve seen so much through the film. The lush green is dotted with yellow, peach, pink, red, violet, lavender, and white flowers. The focus isn’t on the color scheme but the varicolored aspect of the garden. Gardens are typically healing elements, but in this film, they also represent the seedy, masculine wild that Frannie and Pauline exist in and are tormented by.

Every time one of them walks through the garden, they’re immersed in it or fascinated by it. The film opens with Pauline submerged in a blissful garden petal storm, one that points to the potential downfall that comes with wading in fantasy, as Pauline does more often. In this final garden sequence, she stands out among the vegetation. Red and green take center stage again. Frannie is covered in blood, a survivor returning from war in an underworld of men.

The hue of blue dawn light gives a calming feel. Combined with the less aggressive depiction of the garden, which is now healing, there is an air of renewal. She saved herself, and now she’s coming back to a new life, a new love, a man chained to a pole in her apartment hoping for her return. But not just any man. Malloy: honest, open, and safe, a man who actually loves women, as Campion puts it.

![Giveaway: Win Tickets To RAMS [Australia Only]](https://fellinis.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/giveaway-win-tickets-to-rams-australia-only.jpg)