NYFF 2020: THE WOMAN WHO RAN: Amusing, Awkward, Authentic

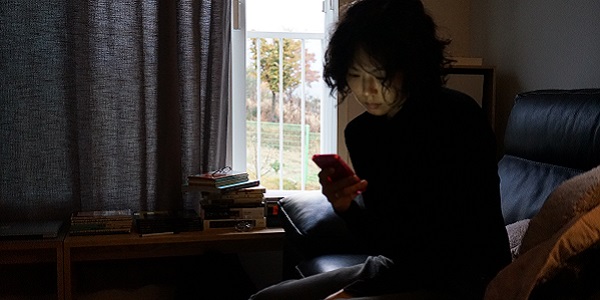

Prolific South Korean filmmaker Hong Sang-soo is back at this year’s New York Film Festival with The Woman Who Ran, a short but sweet portrait of female friendship and the ways that men can intrude on that safe space. Winner of the Silver Bear for Best Director at the 2020 Berlin Film Festival, the film stars Hong’s partner and frequent muse, Kim Min-hee, as a woman who finds herself alone for the first time in five years of marriage and uses that time to visit some old friends. The lengthy conversations that follow, which run the gamut from romance to work to real estate, contain dual undercurrents of social awkwardness and longstanding warmth that should feel authentic to anyone who has ever caught up with friends after a series of life changes and found them to be both familiar and strange.

Getting To Know You…Again

The first stop on Gam-hee’s (Kim Min-hee) journey is the home of Young-soon (Seo Young-hwa), a divorced friend who has moved to a home in the shadow of the mountains on the outskirts of Seoul, with chickens as well as humans for neighbors and stray cats for children (more on them later). Gam-hee recently chopped off her long wavy hair into a chin-length bob, which Young-soon says makes her look like a flighty teenager.

That Gam-hee did the cut herself in her bathroom implies that she is suffering from that very specific brand of boredom that can plague you when you’ve fallen into a pattern of living as an adult that, while fine, lacks the energy and the spontaneity of youth. After all, what else do you do when you need a change in your life but aren’t willing to throw your current life away? As women onscreen from the flapper era all the way through to Fleabag’s Claire will tell you, you cut your hair.

It’s Gam-hee’s first time seeing Young-soon’s new home, and she comes bringing gifts of meat and drink, which they happily and chattily consume alongside Young-soon’s roommate, Young-ji (Lee Eun-mi), despite being torn between their love of eating meat and their appreciation of the soulful eyes of cows. Their conversation is interrupted by the doorbell, where a male neighbor has appeared to complain about the women’s insistence of feeding the stray cats in the neighborhood: his wife is afraid to go outside because she’s afraid of cats, and aren’t people’s needs more important than those of animals?

What follows is one of the most quietly hilarious exchanges I’ve ever seen in the movies, in which Young-ji repeatedly nods and expresses concern over her neighbor’s plight before politely telling him that they will not acquiesce to his request. These cats are like children, and they need to eat, she tells him. But they’re not children, they’re cats, he cries in exasperation, and on it goes, a circular argument with no end in sight.

Gam-hee’s second stop is the flat of her friend Su-young (Song Seon-mi), a pilates instructor who is thrilled with the bohemian nature of her new neighborhood, including the architect living upstairs whom she has a crush on. Like Gam-hee’s earlier visit to Young-soon, their conversation is also interrupted by a man at the door, this time the young poet with whom Su-young drunkenly slept with once and now cannot get rid of, much to her regret. Similar to the previous male intruder, the poet is primarily shot from behind, with the focus instead on Su-young and the frustration she feels at not being able to get this guy out of her doorway, no matter how brutally she insults him. His unwelcome presence contrasts sharply with the glowing portrait of her new life that Su-young painted for Gam-hee in an attempt to impress her, or perhaps even ignite jealousy.

As with the neighbor who complained about the cats, Gam-hee’s involvement in the exchange is similar to ours in the audience: hovering on the periphery as an intrigued spectator. Watching Gam-hee watch them, it feels as though Gam-hee is trying to absorb as much about her friends’ different ways of life as possible. Does she want to be in their shoes? Not necessarily — both interactions are proof that the grass is not always greener on the other side, despite how much the other side might want you to think otherwise — but she does seem to enjoy the thrill of living vicariously through them and their little social dramas before returning to her own quiet life.

Women Without Men

Gam-hee’s third encounter with an old friend is the only one that is unplanned; when she decides to take herself to see a movie she runs into Woo-jin (Kim Sae-byuk), who happens to work at the theater. Their initial interactions are cautious, as though they are circling each other to confirm that they come in peace and not in anger. The reasons for this are quickly revealed: Woo-jin is now married to Gam-hee’s ex, a well-known novelist who happens to be giving a talk at the theater that same day. But the moment in which Woo-jin reaches out to grasp Gam-hee’s hand and express how sorry she is for what happened between them, one can feel the palpable tension between them melt away to be replaced by the warmth that was always there beneath the surface.

Throughout The Woman Who Ran, the focus is on women and the ways they interact with each other versus the ways they interact with the men in their lives. There’s something hilariously self-aware about the way Hong portrays these men, who all seem to think they are the center of the universe but whose faces are barely even onscreen, sidelined for the sake of the women. When Gam-hee speaks of her absent husband, she sounds content, but there’s something about the rehearsed spiel she recites when explaining why this is her first time alone in years that also speaks of a desire to re-engage with what makes Gam-hee an individual, as opposed to a wife. “He says people in love should always stick together. It’s natural,” Gam-hee explains, each time sounding like less of a true believer in her husband’s words. By the time she’s saying this for the third time, to Woo-jin, one can sense that she’s planning on taking more time apart for herself in the future.

Shot simply with long takes that allow one to be swallowed up by the conversations being had, and with a running time of only 77 minutes, The Woman Who Ran feels in some ways like a trifle. Yet to dismiss the film as such does a disservice to the subtle ways in which Hong and his collaborators explore the everyday drama — both big and small — inherent in human relationships. Even the dysfunction on display here is painfully, poignantly natural. Hong’s artistic fingerprints are all over it, including in the lilting music he composed that is used as a bridge between each of the film’s three chapters. And as Gam-hee, Kim is occasionally enigmatic but always enthralling, with the kind of screen presence that turns even solo moments of quiet contemplation into something cinematic.

Conclusion

With Hong at his most delightfully Rohmer-esque and Kim at her most effortlessly charming, The Woman Who Ran showcases humanity at its most amusing, awkward, and authentic.

What do you think? What is your favorite film by Hong Sang-soo? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

The Woman Who Ran is screening as part of the Main Slate at the 2020 New York Film Festival.

Watch The Woman Who Ran

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Join now!