‘Lovecraft Country’ Is Haunted by the Ghosts of Real-Life Places

In the third episode of Lovecraft Country, the 10-part horror drama series from HBO, a character named Letitia “Leti” Lewis moves into an all-white neighborhood on the North Side of Chicago. Leti, who is played by Jurnee Smollett, is prepared for backlash from her neighbors. What she isn’t prepared for is a basement haunted by the ghosts of a white physician and the African Americans he experimented on and killed.

As shocking and extreme as these events may seem, they closely mirror real-life trauma and violence that African Americans have faced for 400 years. “So many of our characters are based on something true and historical,” says Shannon Houston, the executive story editor of Lovecraft Country. “That particular storyline that we’re telling is really about the history of the medical industry in the United States and its racist practices against Black people, against Black women.”

The ghosts in Leti’s basement eerily resonate with the story of J. Marion Sims, who is sometimes referred to as the father of gynecology. Sims performed inhumane, experimental surgeries on enslaved Black women and children in his backyard hospital in Montgomery, Alabama. Three ghosts in Leti’s basement—Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey—are named for real women whom Sims experimented on.

The history of Black suffering for white gain, from Sims’s experiments to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, is one reason that many African Americans avoid going to the doctor, and particularly to hospitals, says Brandon Jones, a psychotherapist who teaches at Century College in Minnesota. “We have these places and spaces that do hold a lot of pain and trauma, and if we know about the stories behind it, those are places we try to avoid,” Jones says. Research has shown that patients from minority groups report higher levels of mistrust in the medical system, and are most likely to miss appointments or delay care.

In the show, Leti’s 13-room house is the place where Hiram Epstein, a fictional white physician from the University of Chicago, experimented on Black people who may have been kidnapped by a local police officer, Captain Seamus Lancaster. “We found the body parts of eight n*ggers buried in a room beneath the basement,” Lancaster tells her during an arrest. “So if history is any indication, you won’t last in that house very long.”

Even in death, Epstein refuses to accept that a Black person could ever share his space, and the spiritual weight of brutalized Black bodies remains in the house. Leti is forced to lean on her own spiritual convictions to stake a claim on the property.

Lovecraft Country, from showrunner Misha Green, follows a cast of Black characters on a road trip across the Jim Crow-era United States. It’s based on an eponymous novel by Matt Ruff, and takes its name from the writer H.P. Lovecraft, whose own work often featured bigoted and racist narratives. In his 1936 novella “The Shadow over Innsmouth,” Lovecraft argues in favor of racial purity, writing that people of color are impure and therefore less than human. In his 1912 poem “On the Creation of N*ggers,” Lovecraft describes God’s creation of Black people: “A beast they wrought, in semi-human figure,/ Filled it with vice, and called the thing a N*gger.”

Another of the show’s main characters, Atticus “Tic” Freeman, played by Jonathan Majors, recounts how his father made him memorize Lovecraft’s poem so that he would stop reading works by Lovecraft. The main characters in Lovecraft Country fight not only Lovecraftian monsters, but also white supremacy. It weighs heavily on them, both spiritually and mentally, as they suffer from violence and persecution in locations both fantastical and historical.

Lovecraft Country’s exploration of Black suffering and spirituality resonates with the idea of spiritual warfare, which could be described as a kind of inner resistance to both physical and spiritual threats, and to injustices such as racism. C. Vanessa White, an associate professor of spirituality and ministry at Catholic Theological Union, points to a long tradition of worship as a tool that Black people use to survive. “In those sites where there has been trauma, where there have been horrible things that happened, spiritual rituals can help us journey through that and help release that which is bound,” White says. Leti instinctively knows to call an Orisha woman to purge the spirits from her home, and her protection spell also keeps racist police officers and the white daughter of a cult leader from entering her home.

When Leti purchases her home in an all-white neighborhood on the North Side of Chicago, she begins to reclaim her life, and she gains something tangible to call her own. Her trailblazing act in the show was inspired by other, real-life figures who made similar moves as a means of upward mobility, even in the face of backlash. “We wanted to tell the story of Black people pioneering into white neighborhoods,” says Houston, the story editor. “They were moving into neighborhoods where they were not wanted, and they fought to stay there, and they went through hell to stay there.”

This is a more complex story than some historical narratives that celebrate racial integration. In midcentury Chicago, white mobs incited riots by attacking Black people who moved into all-white neighborhoods. In 1946, one such riot broke out in temporary housing for white veterans in West Lawn and West Edelson, and in 1951, another targeted a new Black family in Cicero.

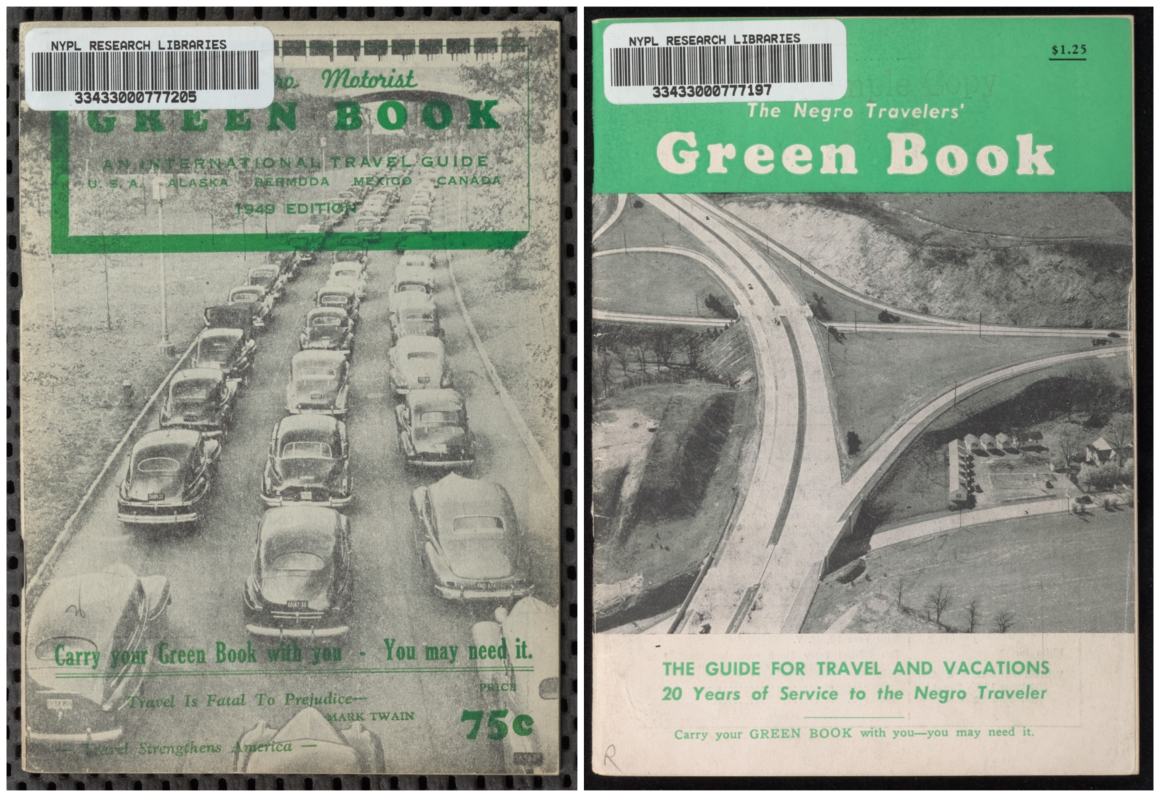

Episode one, “Sundown,” of Lovecraft Country is also full of places where people of Black ancestry are unable to venture because of their race. Tic’s uncle George, played by Courtney B. Vance, is the editor of The Safe Negro Travel Guide—the show’s take on the real-life Negro Motorist Green Book—and guides Leti and Tic through sundown towns and “white-only” establishments. At a diner that was once marked safe for Black travelers, they find out under a hail of bullets that it’s no longer welcoming to their race.

One other setting in Lovecraft Country, Braithwaite Manor, has a strong similarity to a historical site of Black trauma: LaLaurie Mansion, a New Orleans building once owned by the infamous Madame LaLaurie. Born Marie Delphine MacCarthy, LaLaurie gained a reputation for cruelty toward the people she enslaved in her three-story mansion. According to newspaper reports, her sadism was exposed after the mansion went up in flames, allegedly set by an elderly enslaved cook who was chained to the stove in her kitchen. One paper reported that LaLaurie had tortured numerous Black people.

In the show, Tic is held captive and tortured in Braithwaite Manor—but he is saved by the ghost of his enslaved ancestor, who burns the building to the ground. Tic escapes, and he soon leaves Braithwaite Manor behind. Still, the show seems to suggest, the trauma of the past lingers on. All the characters can do is fight back and focus on the future.