The Lost, Macabre Art of Swedish Funeral Confectionery

Attendees at the funeral of Adolf Emanuel Kjellén, in the autumn of 1884, received beautiful, solemn keepsakes. Small, sugar-sculpture doves perched among black lace and fabric flowers, all affixed to pieces of black paper. Inside each elaborate wrapper was a morsel of hard candy. Some mourners even flipped such mementos over and left heart-wrenching inscriptions. Adolf’s mother, Maria, wrote the following: “Our beloved son Adolf Emanuel died on October 28—Maria Gustaf Kjellén.”

Today, Maria’s somber sweet belongs to Stockholm’s Nordiska Museum, as part of their collection of Swedish funeral confectionery. The candies were part of a larger 19th-century trend among the Swedish upper class, in which families distributed ornately-decorated candy at important events. In addition to funeral candy, there was intricate wedding, baptism, and anniversary confectionery. For these happier occasions, the wrappers featured bright colors and images such as babies, crowns, or pink ribbons.

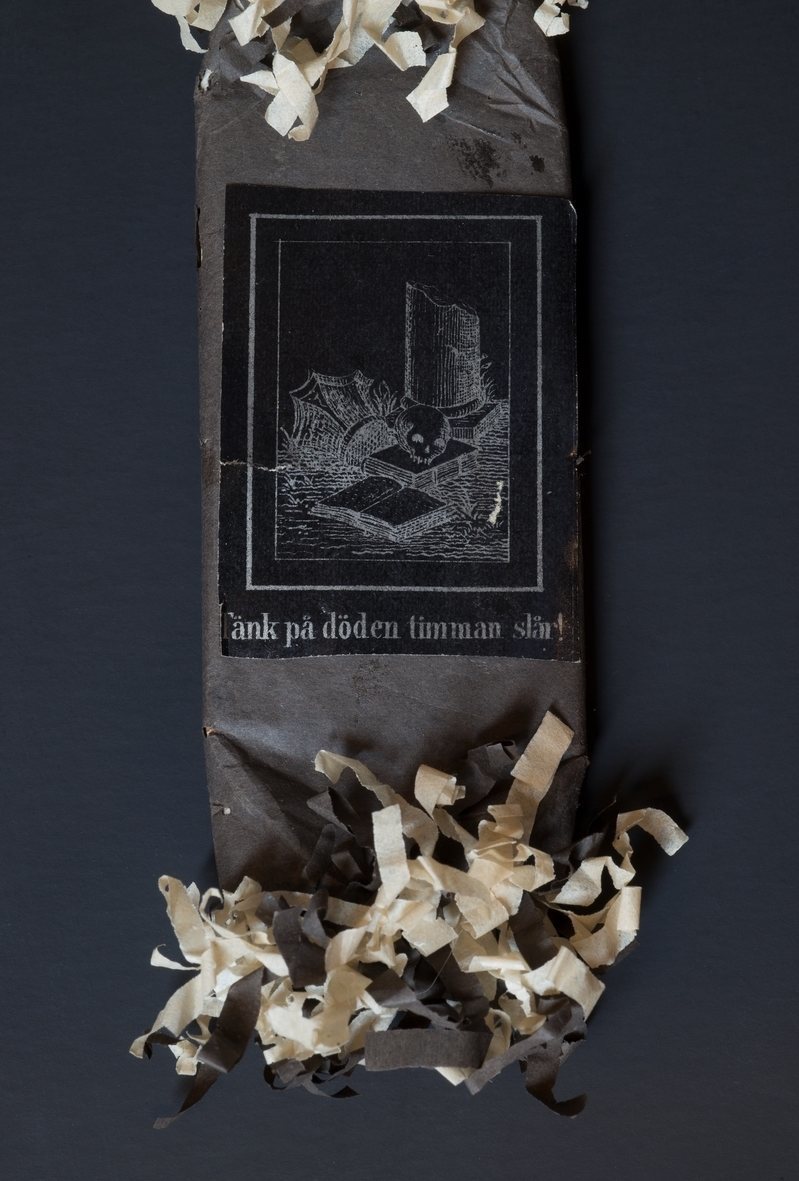

But funeral confectionery design was often downright macabre. There may have been sweets inside the wrappers, but the candies did little to sugar-coat the sad occasion, with wrappers carrying lithographs of skulls, graves, and skeletons.

“The thinking was, ‘We’re dealing with death here and a great loss,’ so visually the expressions were gloomy and morbid,” says Ulrika Torell, a curator at the Nordiska Museum and the author of Sugar and Sweet Things: A Cultural-Historical Study of Sugar Consumption in Sweden. “You were not making something milder than it really was.”

Take, for instance, the candy that marked the passing of “Mrs. Svedeli” in 1844. Its wrapper depicts a skeletal figure snipping the strings of time with scissors. If the message wasn’t clear enough, it also features a scythe resting beneath an hourglass.

Even children’s funeral confectionery didn’t shy away from the stark finality of death. According to the inscription on a candy wrapper, Ernst Axel Jacob von Post was “baptized in distress” shortly after he was born on May 3, 1871, and died the next day. Attendees at his memorial received sweets enrobed in white paper—a common color denoting a child’s death—with a glossy black label that bore a tombstone and a skull and crossbones.

The symbolism of the beautifully designed confections was far more important than the sweets inside. As sugar was a valuable commodity, the candies were precious objects meant to be treasured, not eaten. Typically, the sweets themselves were a mixture of sugar and tragacanth—a gum-like adhesive that bound the sweet together. According to Torell, some confectioners would even use chalk or other cheap materials in the candies to reduce costs, thinking no one would eat it. “They were hard like stone. There are stories of children who made a terrible mistake and tried to eat these candies,” she says. Not only was eating funeral confectionery ill-advised, it was also often considered disrespectful.

By the end of the 19th century, funeral confectionery had spread throughout Sweden, from the bourgeoisie in the cities to the peasants in the countryside. When beet sugar became increasingly available and inexpensive in the late 1800s, the once-opulent commodity became more accessible. As business boomed, an entire industry sprouted up around ritual confectionery. Many Swedish confectioners took annual visits to printers in Germany and France to stock up on supplies for their wrappers. Preprinted images also allowed lower classes to make their own candy and purchase labels from their local confectioner.

These imported labels led to a distinct shift in the candy’s imagery. Taking a turn for the rosy and religious, the artwork saw its skulls, coffins, and graves replaced by angels, Jesus Christ, and the Virgin Mary. “The images became more anesthetized and standardized expressions for grief,” Torell says. “You could see the modernization of mourning with these mass-produced images.”

As sugar became commonplace, it lost its ritual significance. You no longer needed to wait for a special occasion to bring out sweets. Swedish funeral confectionery, as a practice, started to fade in the 1920s and 1930s, dying out completely by the 1960s. Today, it has all but disappeared. The only place you’re likely to find these confections, with their creased paper and fading skulls, would be inside a museum or in an elderly Swede’s attic. But they highlight a unique period in Sweden’s history, when sugar held immense symbolic power.

“They are so full of concern and love,” says Torell. “It was a time when everything was so expensive. So a little sweet with black paper, shining with a cross and a Madonna, it was really something special.”