One of Dracula’s Often Overlooked Inspirations Is the Indian Vetala

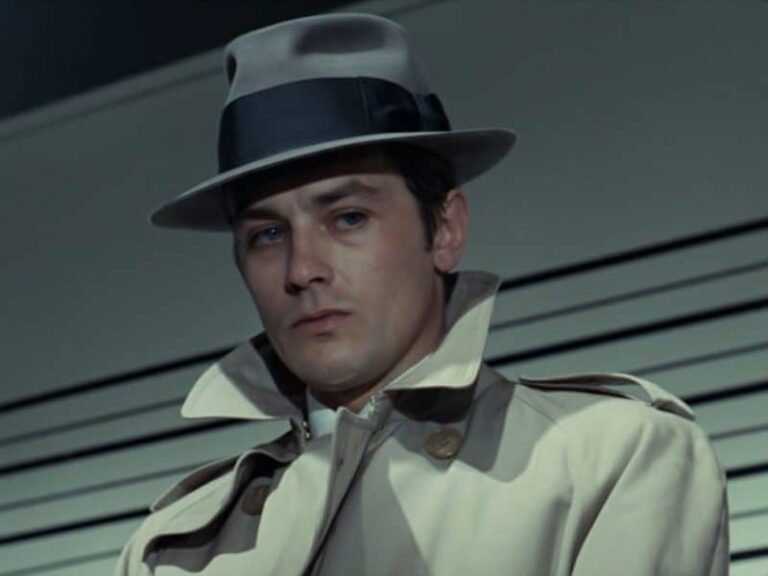

Across generations and around the world, the name “Dracula” now calls to mind a pale man in a tuxedo and cape, eyes bloodshot and fangs gleaming. Originally introduced in Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel of the same name and given that familiar look by Bela Lugosi in 1931, Dracula has since become the world’s prototype vampire, spawning a world of imitations, variations, parody, and more, from Lestat de Lioncourt to Edward Cullen.

Stoker’s Dracula is widely believed to have been inspired by Vlad III, ruler of Wallachia, in what is now Romania, in the 15th century. But few are familiar with another, older creature that is believed, in part, to have contributed to his creation: the Hindu spirit known as the vetala.

As legend goes, the vetala is a ghoulish trickster of varying description that haunts cemeteries and forests, hanging upside down from trees and waiting for humans to play pranks on. They are said to exist in a realm between life and death, and have the ability to see into the past, present, and future. This boundless knowledge makes them invaluable to sorcerers, who often seek to capture and enslave the vetala to use its powers for their bidding. “Growing up, my father taught me that the vetala could see everything,” recalls a priest at the Pasadena Hindu Temple in Los Angeles, who grew up in the Indian state of Gujarat and wished to remain anonymous. “They could detect the good and the evil inside you. We were forever cautious around cemeteries. Because you never knew what might be waiting for you.”

The vetala legend dates back to the 11th century, when it was made popular through Vetala Panchvimshati, a collection of stories that children in India still read today, also known as Baital Pachisi. “My first introduction to the vetala was in school,” an Indian mother interviewed for this piece, who also wished to remain anonymous, says. “We used to get these graphic novels called Amar Chitra Katha, each of which would narrate an Indian story, some of which were historical, some mythological, and some folk.” The Amar Chitra Katha comic books, which included stories from Vetala Panchvimshati, were often shared with cousins and neighbors at home, or passed around during free time at school.

In this collection, originally written in Sanskrit, a tantric sorceress asks King Vikrama to capture a vetala. Each time the king approaches the creature, however, it presents him with a riddle, along with some unusual rules: If the king knows the answer, the vetala will go free, flying back to its upside down perch. If the king does not know the answer, the vetala agrees to be taken as his captive and to go with him to the sorceress. And if the king knows the answer, but does not speak it out loud in an attempt to outsmart the vetala, his head will explode into a million pieces.

Vetala Panchvimshati features 25 stories with the same conceit, and in 24 of them, the king answers the riddle correctly. Thus, again and again, the vetala escapes the sorceress. But the 25th time, the vetala asks the king the following: If a prince marries the queen, and a princess marries the king, and each couple has a baby, what is the relation between the two newborns?

This weird, incestuous question is what finally stumps the king. Because he does not know the answer, the vetala is forced to go with him to the sorceress. But during the journey, the vetala reveals that the sorceress plans to use its powers to kill the king and take over the realm. The two then decide to team up to kill the sorceress. After peace has been restored, the vetala offers to protect the kingdom and come to the king’s aid whenever he needs it.

While this popular story depicts the vetala as a trickster with the capacity for good, today the vetala is characterized as far more demonic. In The Mythical Creatures Bible: The Definitive Guide to Legendary Beings by Brenda Rosen, the vetala is called a “hostile spirit said to cause madness, miscarriages, and kill children.” Likewise, in Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures by Theresa Bane, the vetala is defined as a “vampiric demon” that possesses humans and causes their feet and hands to twist backwards, their skin to turn green, and their fingernails to become long, poisonous white talons.

These descriptions are far cries from the original Sanskrit text of Vetala Panchvimshati, in which the vetala is depicted as a more nuanced creature. And this transformation can be blamed, at least in part, on British explorer, writer, and gadabout Sir Richard Burton, who was the first person to bring both the Kama Sutra and Vetala Panchvimshati to Western audiences.

To his credit, Burton never claimed that Vitram and the Vampire was an exact translation. “It is not pretended that the words of these Hindu tales are preserved to the letter…. I have ventured to remedy the conciseness of their language, and to clothe the skeleton with flesh and blood,” he wrote in the introduction.

But Penzer’s response to this disclaimer doesn’t mince words: “This is putting it very mildly. What Burton has really done is to use a portion of the Vetāla tales as a peg on which to hang elaborate ‘improvements’ entirely of his own invention.” Regardless of scholars’ critiques, the damage had been done. Vitram and the Vampire was marketed as the English translation of Vetala Panchvimshati, and readers took the depiction of the vetala as authentic.

One of those readers was Bram Stoker. The author greatly admired Burton and was fascinated by his writings about the Indian occult, and particularly Vetala Panchvimshati. Dracula’s transformation into a bat that hangs upside down, for example, his reptilian-like climbing abilities, his powers, and his centuries of wisdom all may have been drawn from Burton’s translation.

Since Dracula’s publication, the vetala has remained alive and well, but in recent years, it has morphed into something closer to Burton and Stoker’s idea of the spirit. In one 2012 episode of the CW show Supernatural, for example, the protagonists face off against two seductive vetalas, depicted with sharp fangs and a thirst for blood that make them more or less indistinguishable from other pop-culture bloodsuckers.

Indian production companies have also capitalized on what is a more homegrown horror movie villain. In 2020’s Betaal (now streaming on Netflix), a remote village falls prey to a colony of vetala working alongside officers from the East India Company to take over their land. In the movie, the vetala is reimagined as a vampire-zombie hybrid.

The modern vetala, then, is an amalgamation of cultures, stories, and misinterpretations—adopted, adapted, and then adopted again. And while the vetala of today’s pop culture is a far cry from the original text, those stories remain in the hearts of Indian children and grownups.

When asked whether he believes the vetala exists in some form on Earth, and whether it might have an influence on us, the priest at the Pasadena Hindu Temple leaves things open. “As with any myth, any frightening story or creature, some people believe, some don’t,” he says. “But I’ve found that when something goes amiss, when there’s a sound in a cemetery, an unexplained shadow or disturbance, people change their minds.”