How Acupuncture Became a Radical Remedy in the Bronx

In the early 2000s, Juan Cortez was living in New York City and battling a years-long addiction to drugs, when he noticed a crowd of people standing outside a building on East 140th Street in the Bronx. Recognizing the group as fellow users, he approached and asked what was inside the building. Cortez, who was in his late 20s, with a lean build and ever-present Yankees hat on his shaved head, was told it was a recovery program. Part of the treatment involved getting acupuncture every morning.

At Lincoln Hospital’s Recovery Center, Cortez eventually succeeded in overcoming his addiction, using a combination of acupuncture and other therapies. He went on to become a trained acupuncturist and is now manager of holistic services at New York Harm Reduction Educators, a nonprofit social-service organization that provides walk-in and mobile holistic services to the city’s houseless or marginalized residents.

“When you think about acupuncture, massage therapy, Reiki, yoga, sound therapy, you think about a ‘spa day,’ you think about people that have money who are able to attain those services,” Cortez says. “Not poor people in the projects.”

While there remains ongoing scientific debate as to the efficacy of acupuncture and traditional Chinese medicine in treating addiction, some practitioners believe it has myriad benefits, particularly in helping with anxiety, inflammation, and stress. But the story of how acupuncture came to be a widespread treatment in the United States—sometimes associated most commonly with privilege—begins nearly 50 years ago, in New York’s South Bronx, with a subversive alliance of Black and brown activists.

On November 10, 1970, more than two dozen members of the Puerto Rican activist group Young Lords, alongside members of the Black Panther Party, occupied the sixth floor of Lincoln Hospital, in the South Bronx. With heroin devastating Harlem and the South Bronx, the protestors demanded a long-promised drug treatment program, staffed by former users, that would “serve the community effectively and be run by the community.”

The following day, the People’s Program was informally established, and within hours, 200 people had formed a line outside the building seeking methadone, an opioid that helps ease the symptoms of heroin withdrawal. After days of tense negotiations between the Young Lords and hospital administrators, the drug detoxification program was granted funding and recognition. Staffed largely by volunteers, the People’s Program operated out of Lincoln Hospital’s auditorium, meagerly furnished with about 40 chairs, 20 tables, and a few cubicle curtains for privacy. The walls were decorated with posters of Angela Davis, Malcolm X, and Chairman Mao. It looked less like a clinic than a community center for young leftists—which, in a way, it was.

Cleo Silvers was then a 20-year-old community mental health worker at Lincoln Hospital and former organizer with VISTA, or Volunteers in Service to America. She was also co-chair of the activist group Health Revolutionary Unity Movement and a member of the Black Panther Party’s Harlem chapter. “In the Constitution, you are supposed to have the right of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” Silvers says. “But you cannot have life if you don’t have health.”

While Black Panthers are today commonly associated with armed protest and the rhetoric of self-defense, the party was just as invested in community outreach and wellness. “It’s at the core of demands for people who are disenfranchised, who are poor, who don’t have access to the possibility of living a good life because they are subject to all of these illnesses that can be prevented,” Silvers says. She conducted neighborhood health surveys, door-to-door sickle cell anemia testing, and helped to initiate a ban on lead-based paint in residential buildings. She later joined the Young Lords, supported the occupation of Lincoln Hospital, and assisted with the detox program.

“Healthcare was very difficult for poor people to get,” says Tolbert Small, who worked as a physician for the Black Panthers in the 1970s. “The people who went on to make radical changes in our society felt that healthcare, food, and education were all important.”

Black and brown Americans historically have received substandard health services compared with white Americans, including for cancer, HIV, prenatal, and preventive care. Patients of color have also been under-treated for pain symptoms compared to white patients. Bias and unequal access to healthcare continue to contribute to higher rates of illness, including COVID-19, in Black and brown communities.

“They were seeing what was happening in their community—the social injustice, the lack of medical care, the lack of resources,” says Cortez. “While other communities were thriving, the community of the South Bronx and other poor communities around the country were deteriorating, and there was nothing being invested in these communities, nothing being invested for the people. So they did what they had to do for the people.”

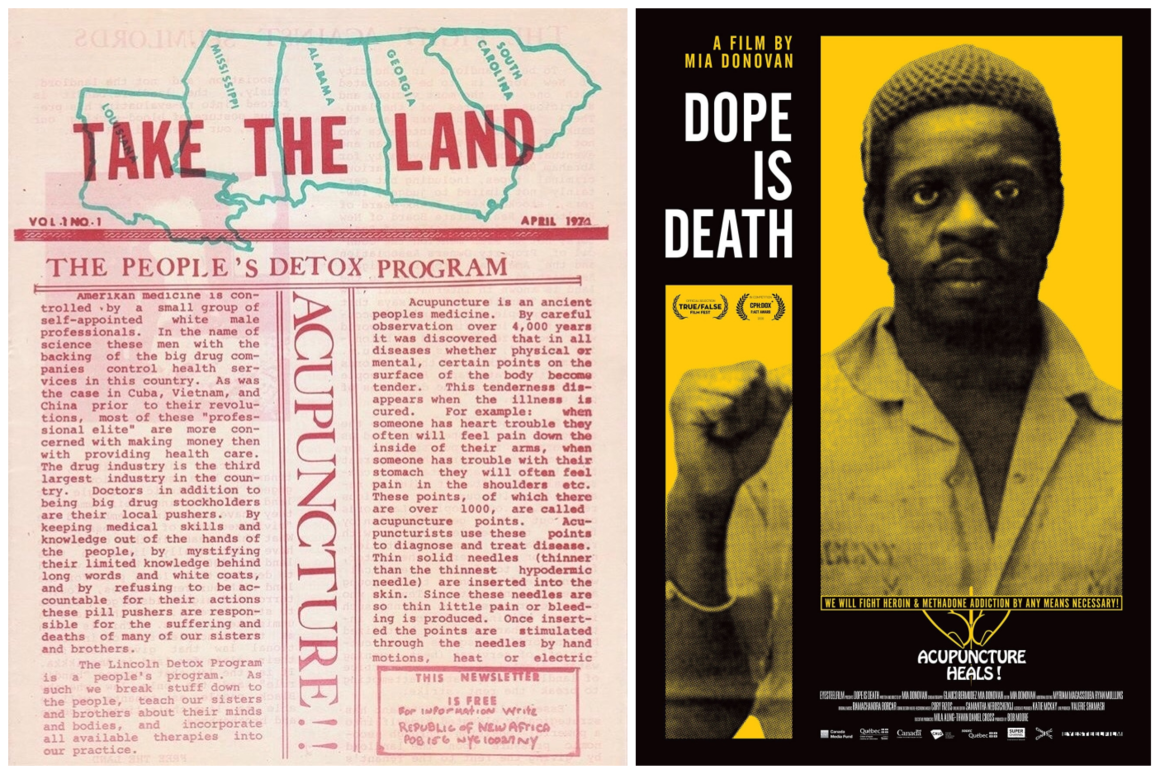

In tandem with its drug-addiction treatment, the People’s Program held political education classes and distributed illustrated posters and newsletters featuring a clenched fist destroying a syringe, or a skull-and-crossbones wearing an Uncle Sam hat. They portrayed heroin as a form of chemical warfare that pacified Black and brown resistance against the substandard conditions they were living in, and the social injustices they routinely faced.

The activists reported that police themselves sometimes brought heroin into Harlem and the Bronx. Once, Silvers says, she was out selling Black Panther newspapers and started chatting with two teenage boys who were nodding off from the effects of heroin. She says that a police officer drove up, parked nearby, and began selling heroin out of the squad car. These illicit deals were documented by the Knapp Commission, which investigated corruption in the NYPD.

Lincoln Detox at first administered methadone, a commonly used and FDA-approved treatment for kicking heroin. But methadone, a synthetic opioid, is itself addictive. The staff at Lincoln Detox sought an alternative treatment that could be natural, inexpensive, and allow for greater autonomy, and that eventually led them to acupuncture.

“There was an awareness that methadone was another form of control,” says filmmaker Mia Donovan, director of the film and podcast Dope Is Death, which documents the history of Lincoln Detox. “It was governed by the State and Big Pharma. They knew there was an alternative way to treat addiction. And then it also became like, ‘This can help us towards self-determination.’”

In 1970, Lincoln Detox hired a young activist named Mutulu Shakur as director of political education. Shakur was affiliated with the militant Revolutionary Action Movement and the Republic of New Afrika, a Black nationalist and separatist group that advocated for an independent Black nation in the American South. Shakur read a 1973 New York Times article about the early successes of Hong Kong doctors who were using acupuncture to treat withdrawal symptoms of substance abuse. He was also stirred by the work of the so-called “barefoot doctors,” who were providing basic, low-cost, grassroots medical care in Maoist China. Chinese medical practitioners had practiced acupuncture for millennia, but at the time, it was largely unfamiliar to Westerners.

Tamara Venit-Shelton, associate professor of history at Claremont McKenna College and author of Herbs and Roots: A History of Chinese Doctors in the American Medical Marketplace, says that acupuncture in Communist China was “designed to be taken out to rural areas, to be administered by people with relatively little training, and to provide comprehensive, generalized, and preventative care to communities who weren’t being served by hospitals.” After the Revolution, as migrants fled China to the United States, they brought this egalitarian approach to healthcare with them.

“I see Lincoln Hospital as being part of that history,” Venit-Shelton says. “Practitioners of acupuncture are thinking about how to democratize access to good medical care, how to be anti-colonialist and anti-capitalist in their approach to healthcare.”

Shakur and others received acupuncture training in Quebec and California and, in 1976, he became certified and licensed to practice acupuncture in the State of California. (He also married Afeni Shakur, and was stepfather to her son Tupac until they divorced in 1982.) Shakur returned to New York and established Lincoln Detox’s acupuncture training program, one of the first of its kind in the country. “He brought acupuncture to the forefront as a method of helping people with addiction,” says Silvers, who worked alongside Shakur. “The work that he did was stellar.”

“What he was doing at Lincoln Hospital was really quite countercultural,” says Venit-Shelton. “Mutulu Shakur was drawing on a global countercultural current, and creating a kind of model for how it could be done in the United States.”

Lincoln Detox attracted controversy almost from the beginning, and not only because of its ideological commitments. The clinic faced allegations of millions of dollars in dubious payroll costs and expenditures; patients were billed four times as much as patients at citywide clinics. On the morning of October 29, 1974, Richard Taft, a white doctor at the clinic, was found dead inside a closet from an apparent overdose, though some Lincoln staff alleged that he was assassinated. On November 27, 1978, Chuck Schumer, the Brooklyn Democratic Assemblyman and future U.S. Senate minority leader, accused the city and state of “protecting a ripoff drug-treatment program through years of continuing scandal.” Then New York City’s mayor, Ed Koch, accused Lincoln Detox of harboring leftist radicals. “Hospitals are for sick people, not for thugs,” he declared. He ordered the NYPD and Lincoln Hospital, a public institution, to expel the People’s Program from the premises.

After the People’s Program was ousted from Lincoln Hospital, the drug-recovery program relocated to a building on East 140th Street, where the five-point approach to acupuncture was further developed. It has since been standardized as the NADA (National Acupuncture Detoxification Association) protocol. According to NADA estimates, there are now more than 600 programs in the United States that use acupuncture as a method of addiction recovery. NADA has trained more than 10,000 health professionals in North America and more than 25,000 healthcare providers in more than 40 countries. Shakur, meanwhile, co-founded the Black Acupuncture Advisory Association of North America, where he continued to treat patients and train apprentices in acupuncture and political education. He spoke at medical conferences throughout the country and visited the People’s Republic of China.

Shakur’s career came to a sudden and violent halt in 1981, after the robbery of a Brink’s armored car in Nanuet, New York, during which two police officers and a Brink’s guard were killed. Though Shakur wasn’t present at the robbery, he was accused of being the ringleader. He went “underground,” or into hiding, and was soon added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. Shakur was captured in California in 1986 and convicted in 1988 under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO. In October 2019, after more than three decades in prison, Shakur was diagnosed with life-threatening cancer, and his supporters are currently campaigning for his compassionate release.

For today’s acupuncturists of color, the example set by Shakur, the Young Lords, and the Black Panthers laid a foundation for community-based alternative medicine. “They taught us how to take these things and bring them into our own community, so that we can take care of ourselves and not be dependent upon doctors,” explains Tenisha Dandridge, a Sacramento-based acupuncturist and co-founder of BlackAcupuncturist.com. “We can use this medicine to start closing the health disparity gaps that exist because melanated humans in the United States live unnaturally stressed lives.”

Shadidi Kinsey, the founder and director of Bedford-Stuyvesant’s PEACE Health Center, studied under Shakur in 1981. She credits him with helping spread acupuncture as a treatment for addiction in the United States, and she sees it as “a vital tool to bring well-being to our community.” This tradition has grown far beyond its radical roots. “He’s the one who brought this into being,” she says. “It went from the South Bronx to the world.”