Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet is as Irreplaceable as Ever

2020 has been a strange year for cinema, but its unpredictability has made room for reassessment. The lack of new Shakespeare adaptations hitting U.S. theaters provides us with an opportunity: to revisit Baz Luhrmann’s “Romeo + Juliet,” released 24 years ago this month. A modern spin on the romantic tragedy defined by Luhrmann’s affective style, Jill Bilcock’s frenetic editing, and that banger of a contemporary soundtrack, “Romeo + Juliet” was a runaway success that made the romantic tragedy an obsession for a new generation of viewers. Leonardo DiCaprio’s face helped, of course. For millennials of a certain age, the smoldering glare of his introduction, set to Radiohead’s “Talk Show Host,” remains a formative spark of sexual discovery. But DiCaprio at the peak of his blonde-banged allure isn’t the only draw here: costars Harold Perrineau and John Leguizamo are forces of nature whose performances add much-needed diversity to a story that too often—like so many Shakespeare adaptations—is imagined as a monotony of whiteness.

As Mercutio, Romeo’s hotheaded best friend, and Tybalt, Juliet’s (Claire Danes) volatile cousin, Perrineau and Leguizamo, respectively, are hurricanes of charisma every time they appear onscreen. As Black and Latin American men, the actors bring complexity and depth to Luhrmann’s depiction of Verona Beach, and their presence complicates our traditional ideas of tribalism. As the conversation about diversity, inclusion, and representation in film has taken on a more impassioned tone in recent years, Perrineau and Leguizamo demonstrate the value added of such equity. Frankly, they’re phenomenal, their highly tuned performances giving “Romeo + Juliet” the thrill and danger needed to make its calamities even more impactful. Although “Romeo + Juliet” wasn’t singular in this casting approach (Kenneth Branagh’s 1993 version of “Much Ado About Nothing,” for example, included a very good Denzel Washington and a trying-his-best Keanu Reeves in its ensemble), it remains iconic for how intentionally it subverted our expectations of Shakespeare’s world and the characters who could live within it. “You want me? F—ing come and find me,” Thom Yorke sneers in “Talk Show Host,” and how convincingly Perrineau and Leguizamo made real the antipathy between the Montagues and Capulets helped immortalize “Romeo + Juliet” into a film that has since proved impossible to replicate or replace.

“I will burn for you

Feel pain for you

I will twist the knife and bleed my aching heart

And tear it apart.”

—“#1 Crush,” Garbage

The tale of Romeo and Juliet—feuding families, star-crossed lovers, the whole thing—is ubiquitous, and from its very first frame, Luhrmann’s “Romeo + Juliet” works to undermine what viewers might already associate with it. A wood-paneled television’s staticky screen floats in a sea of deep, impenetrable black, coming closer and closer to us, until a news broadcast switches on. The first person we see, the individual who will guide us through this tale and whom we therefore implicitly trust, is a Black anchorwoman (Edwina Moore). “Civil blood makes civil hands unclean,” she informs, complemented by a pleasantly retro graphic illustration of a broken-apart wedding ring, and Luhrmann then smashes us forward into the crumbling metropolis of Verona Beach.

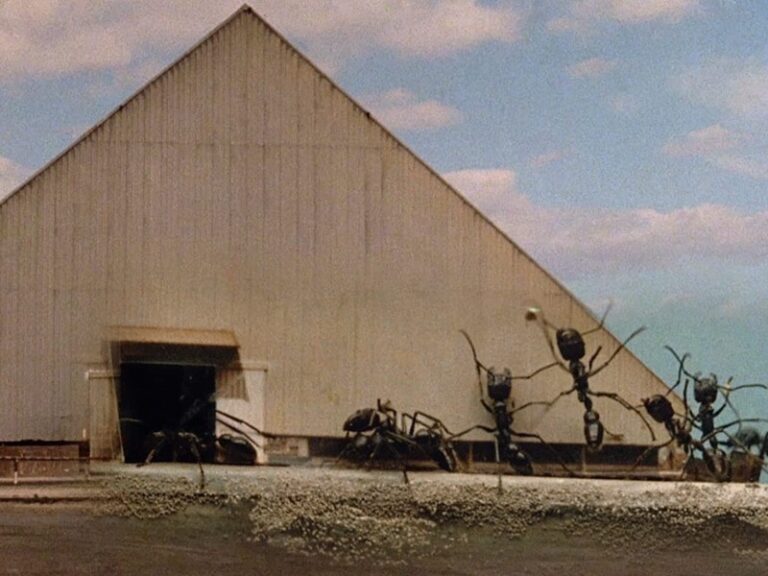

A chaotic mélange of images lays out the scene: Verona Beach is ruled by two families, the Montagues and the Capulets, who have loathed each other for years. Their skyscrapers are situated directly across from each other; the city is almost divided down the middle by their de facto armies; and their violent antics infuriate Police Captain Prince (Vondie Curtis-Hall). The city’s entire journalism industry covers the feud with breathless abandon. And yet even for all Captain Prince’s stern warnings, and even for all the bad press, the rivalry does not let up. The film’s first quarrel captures the heat of all this: At a gas station, the Montague Boys end up insulting the Capulets (Jamie Kennedy’s panicked, then combative, reaction to “Do you bite your thumb at us, sir?” sells it), and it’s an immediate mistake. The Montagues are goofy and undisciplined, and compared with Tybalt Capulet, nicknamed the Prince of Cats, they’re badly outmanned. But could anyone step to the relentlessly put together, obviously dangerous Tybalt? His side part and sideburns are lacquered in a way that evokes the baby-hair styles championed and worn by Black and Latin American women. His bright red vest with a torso-length portrait of the Virgin Mary on it announces his Catholic faith; she appears also on the handles of his guns, as does the Capulet family crest. His black leather boots are decorated with silver toes and heels; on the latter are engraved the face of a wildcat. Double gun belts complete the look. He can, and has, killed a Montague without a second thought, and he always looks exceptional doing it.

Tybalt’s introduction has all the bombastic qualities of a man who has studiously built a formidable persona, and who knows that a certain performance is part of maintaining it. His loathing is genuine—the tight close-up on Leguizamo’s face as he hisses, “Peace? Peace? I hate the word as I hate Hell, all Montagues, and thee” is perfect framing—and his tactics have the intensity of a true believer. How he stamps out a match, viciously twisting his toe in those formidable boots, to fully concentrate on the upcoming fight. How he takes a stance like a bullfighter to duel, guns held high. How he whips off his jacket and drops into a kneel, as if he’s at confession, before reloading his gun, kissing it, and aiming it at the departing Benvolio (Dash Mihok), Romeo’s cousin. In a film with so much aesthetic style, Tybalt’s every movement is titillating. Leguizamo’s intentionality exudes menace: The cherry-red sequined devil horns and vest he wears to the Capulets’ fiesta-style ball could be construed as feminine but lend him demonic glamour. The kiss he shares with Juliet’s mother at that same party is positively carnal; aren’t they supposed to be cousins? Rarely has a man looked this attractive while smoking; as Tybalt watches Romeo leave the party and takes a drag, his “I will withdraw, but this intrusion shall/Now seeming sweet, convert to bitterest gall” is a promise.

On the one hand, you could argue that Tybalt is just another personification of a series of stereotypes about Latin American men and Chicano culture that Luhrmann, production designer Catherine Martin, and costume designer Kym Barrett rely on to depict the Capulets. Tybalt’s henchman Abra (Vincent Laresca), with his “SIN” grill and gigantic religious back tattoo, gets riled up quick. Juliet’s father Fulgencio (Paul Sorvino) is a bully and an abuser, a man who knocks around women and essentially sells his daughter to Paul Rudd’s Paris (“You be mine, I’ll give you to my friend”). But the specific grounding of an ethnic identity for the Capulets (that is not Shakespeare’s original Italian) allows the film not only celebrate certain rituals (like the carnival aspects of the Capulets’ costume party, and the calaca costumes worn to it by Tybalt’s henchmen) but also allude to certain questions of race- and class-based friction and ownership of place. In a city where white and Latinx people are at war, how much of this conflict is tied to power, who gets to wield it, and who is denied it?

At the highest level, the Montague and Capulet parents seem similar in terms of the privilege that wealth allows: they travel exclusively in chauffeured limos; other people hold umbrellas for them in the rain; they’re called before the police captain but never fear retribution. But their heirs and their proxies are the soldiers in this war, and they move between surprising spaces. The Montagues use the beach as their hangout, often surrounded by people of color who tolerate these young men with a level of bemusement. The Capulets are ensconced in a gigantic mansion with a security staff who is mostly white, aside from Juliet’s Nurse (Miriam Margolyes, broadly playing Latina; the brownface isn’t great), who detests having to visit the beach where the Montagues congregate. There is fluidity to who these characters are, what they act like, and what they represent in the story that is more than just cultural tourism. “Romeo + Juliet” did film in Mexico City and Boca del Rio, Veracruz, as well as Miami, but the atmosphere Verona Beach most suggests, save for the gigantic Jesus statue, is California’s Venice Beach. Long a location for quirky artists, wanderers, and lingering hippies, Venice Beach has been increasingly gentrified in the past few decades, its original inhabitants pushed out by skyrocketing real estate prices and corporate developers. This Verona Beach mimicry, with its decaying Sycamore Grove stage plopped right on the beach, much-loved carousel and Ferris wheel, AC-deficient pool hall, and various murals, including that gigantic L’amour painting in Coca-Cola style, might be closer to what Venice Beach used to be like than any part of the community that still exists.

Back to Tybalt: Is it ironic that a man so blunt in his scorn toward an entire lineage would also have a tattoo of a sacred heart upon his chest—a Catholic symbol meant to represent the means of Jesus’s death, and the restorative power of divine love? How can a man so unrelenting in his derision also make space in his soul for such a meaningful depiction of faith? “Romeo + Juliet” thrives on these contradictions, employing them in the film’s arsenal of narrative and anachronistic mashups. How the piety of a man like Tybalt doesn’t quite jibe with his murderous infamy. How someone as wise and revered as Friar Laurence (Pete Postlethwaite) would come up with such a convoluted plot to protect two lust-addled teenagers. And how the silver-tongued, inimitably cutting, delightfully roguish Mercutio, so dismissive of best friend Romeo’s mooning over first crush Rosaline, might have a very good reason for his irritation: He might be in love with Romeo himself.

“Oh, young hearts run free

Never be hung up

Hung up like my man and me

My man and me

Ooh, young hearts, to yourself be true

Don’t be no fool when love really don’t love you

Don’t love you.”

—“Young Hearts Run Free,” Kym Mazelle

Perhaps as a mischievous response to the fact that women couldn’t act onstage during the time of his output, Shakespeare’s plays are full of gender experimentation. “As You Like It,” “The Merchant of Venice,” and “Twelfth Night” all include female characters who dress like men, and whose disguise then raises additional questions about their identity or sexuality. Was that precedent what inspired Luhrmann and co-writer Craig Pearce to transform what was Mercutio’s coarseness in the play into a different kind of boldness onscreen—a willingness to laugh in the face of others’ expectations, and look damn good doing it?

“Romeo + Juliet” is already packed with lively characters by the time Mercutio shows up, but Perrineau is dizzying, dynamic, and irrepressible. His entrance is delightfully manic: introduced in the middle of a peal of laughter, a Marilyn Monroe-style wig covering his dreadlocks, blue-red lipstick smudged on his lips and smeared on his teeth, speeding behind the wheel of a Mitsubishi 3000 GT with custom plates. In a sequined halter bra top and miniskirt, matching glittery T-strap heels, and a gun strapped across his body, Mercutio is a walking “F— you, look at me,” and a stark contrast to the Montague Boys, dressed as miniature versions of the grownups they admire (Kennedy’s Sampson as a Viking; Benvolio as a priest; Romeo as a knight). But there’s no judgment here: They’re delighted by Mercutio’s outfit, they cheer him on as he tantalizingly pulls up his skirt to reveal one butt cheek, Romeo laughs when Mercutio pulls his invitation to the Capulets’ party from between his legs. They know who Mercutio is, and they love him for it. And, as Perrineau plays him (note that “Prick love for pricking” line delivery!), Mercutio adds enough queer subtext to the film to incorporate another dimension of rage and grief to Romeo’s retributive murder of Tybalt.

There’s the drag, of course, but so much more—even though Perrineau is in fewer than a half-dozen scenes, his mercurial performance bends the entire film around him. His flirty offering to Romeo of an Ecstasy pill, which is ostensibly what he’s high on when he delivers his entrancingly enraged Queen Mab speech. The smirking tone of his “And then they dream of love” line, and then the shattering anger of his screamed “This is she!” His startled reaction when Romeo touches his shoulder, and his quick recovery. How clearly he steps into the role of ringleader of the Montague Boys, and then abandons that to wave and sway like a pageant winner boosted up on the backseat of the car during their drive to the Capulets’ party. The effervescent, riotous joy of that “Young Hearts Run Free” performance, and the preparation that must have gone into it: an even-more-voluminous, Diana Ross-style wig, the meticulously fastened thigh highs and garters, the choker necklace, the cape, the gloves. Luhrmann allows his actors to gaze directly into the camera every so often, and Perrineau takes full advantage of that freedom here. He shimmies, he shakes, he gyrates, he wags his fingers at anyone who considers being anything less than true to themselves. Is this, even in its artifice, Mercutio’s most authentic self? Or is it later on, when amused by Romeo—who jumps out of their car as they leave the party, running back to sneak onto Juliet’s balcony—Mercutio calls out, “Humors! Madman! Passion! Lover!”? Is the latter a guess of who Romeo was to become—or perhaps who he already was, at least to Mercutio?

So much of this reading is based on Perrineau’s vibrancy, and his next scene demonstrates his range. Gone are the sequins and the lipstick. Gone too is Mercutio’s patience. This is the renegade version of the character, and his costuming—sheer shirt, slim-fitting jeans, dreadlocks now free, gun casually on his hip—aligns him more with his Montague comrades. “Where the devil should this Romeo be?” he spits out, each syllable in “Romeo” crisp in his mouth, and it is here that Mercutio’s explosivity becomes plain. With Benvolio, he’s a roll-with-the-punches bro; the two pretend to duel on the beach. With Romeo, he’s more physical, wrestling him down into the sand before being confused, and then annoyed, by the Nurse’s presence to deliver a message from Juliet. And as a hurricane brews over the water and Tybalt and the Capulets drive up, Mercutio is ready to attack first with his words (mocking Tybalt’s sexuality, “Could you not take some occasion without giving?”) and then with his fists (when Tybalt turns the innuendo around with, “Thou consortest with Romeo?”). Does Mercutio decide to fight Tybalt because Romeo refrains out of newly found loyalty now that he’s married to Juliet, or because Romeo offers Tybalt love instead of him? Whatever the context, Perrineau’s final moments as Mercutio are the film’s strongest acting and its most compelling heartbreak. The braggadocio still lacing his laugh as he insists Tybalt’s attack was just “a scratch, a scratch,” and then the collapse of his face when the camera pans down to his gaping wound and then back up again to capture his expression, and then the bitterness in his tone when he curses Romeo and Tybalt both: “A plague on both your houses!”

Mercutio’s death finally sparks Romeo’s vitriol, and Luhrmann’s shot composition is exquisite: After cradling his best friend’s body to his chest, Romeo leaves him on the sand before the Sycamore Grove stage. As Mercutio remains in the foreground, Romeo sprints backward to his car, followed by the too-slow Benvolio. Storm clouds gather. Sand whips around. Mercutio grows colder. And in the background, an argument between Romeo and Benvolio—and then Romeo peels out to track down Tybalt. When Romeo shoots him before that gargantuan statue of Jesus, does he pierce Tybalt through the sacred heart tattoo, creating an eerie similarity between the Prince of Cats and his believed savior? Maybe. But at that point, do the details of a death really compare with its utter finality? Of everyone in “Romeo + Juliet” who dares to utter a wish, only Mercutio’s comes true—Tybalt and Romeo will both be dead in a matter of days. “A plague on both your houses,” indeed.

“I know you’ve been hurting, but I’ve been waiting to be there for you.”

—Quindon Tarver, “Everybody’s Free (To Feel Good)”

The 1990s belonged to DiCaprio and Danes, and all of the surrounding pieces of “Romeo + Juliet”—Leguizamo, Perrineau, Luhrmann’s extra-ness, that soundtrack—work in collaboration with their perfect embodiments of Romeo and Juliet. The actors exuded the youth necessary for their characters (DiCaprio, who stayed baby-faced into his 20s, was 21 during filming, while Danes was 17), but more importantly than that, infused each with the besotted fragility and wild desperation needed to convince us of their refusal to “love moderately.”

DiCaprio was already becoming a teen idol after his work in “This Boy’s Life,” “The Basketball Diaries,” and “The Quick and the Dead,” but “Romeo + Juliet” jettisoned the actor to another level of omnipresent stardom. You can ascribe a certain amount of that fame to DiCaprio’s face, of course—to whatever inexplicable combination of genetics and luck provided those aquamarine eyes, angular cheekbones, and impish grin. Those looks would become so desired and so tied to discussions of DiCaprio’s acting ability that after the one-two punch of “Romeo + Juliet” and “Titanic,” he literally retreated behind metal in “The Man in the Iron Mask” and slathered himself in grime in “The Beach.” DiCaprio’s lengthy partnership with filmmaker Martin Scorsese would deepen his expertise at playing characters prone to obfuscating themselves: a 19th century gangster lying about his identity in “Gangs of New York,” a reclusive genius hiding away in “The Aviator,” an undercover police officer in “The Departed,” a U.S. Marshal experiencing a mental breakdown in “Shutter Island,” a businessman defined by his immorality in “The Wolf of Wall Street.” Regardless of DiCaprio’s eventual discomfort with his own physical appeal, however, the introduction he’s given in “Romeo + Juliet” amps it up. A slow pan shows us first his cigarette and journal, then his open shirt collar, then those begging-to-be-smoothed-back blond bangs; silhouetted against the golden sunlight of a setting sun, DiCaprio’s Romeo is as tortured in isolation as he is unquestionably beautiful. His first direct look into the camera is a challenge for us to look away, but why would you?

Romeo’s playfulness and impetuousness come out around the Montague Boys, with whom he has an easy, self-deprecating bond. They’re as united in their razzing of each other as they are in their resentment toward the Capulets, which is of course complicated once Romeo and Juliet meet. The story about Danes’s casting goes that Natalie Portman had been cast as Juliet first, but the age gap between her and DiCaprio urged Luhrmann to go in a different direction. Enter the erstwhile Angela Chase: Danes brings wide-eyed optimism and self-aware skepticism to a character who avoids easy classification as a “good girl.” She rolls her eyes at her mother’s romantic scheming—and unlike Romeo, has no initial stake in the feud between their families—but takes to heart the Nurse’s encouragement to “seek happy nights to happy days.” Something elemental happens when DiCaprio and Danes lock eyes through that aquarium at the Capulets’ costume party, and Luhrmann lets us in on it, rotating between the pair as they rapidly tumble into love, retreat into the elevator for their first kiss, and then commit to vows in Juliet’s balcony pool. Danes is deliberate in her portrayal of Juliet as a young woman aware of the far-reaching ramifications of choosing Romeo, and the little nod Juliet gives DiCaprio’s Romeo once she meets him at the church altar for their wedding is an acceptance of whatever may come.

All Romeo and Juliet get together is one happy night amid Juliet’s crisp white sheets in a room decorated with numerous offerings to the Virgin Mary before Romeo has to flee Verona for killing Tybalt as revenge for Mercutio; before Juliet’s parents abandon her to Paris; before a scheme involving a sleeping potion goes horribly wrong; before Romeo and Juliet end up taking their own lives rather than be forever separated. The final scene of “Romeo + Juliet” is an opulent display of grief—neon-lit crosses, thousands of burning candles, a sea of mourning bouquets—but what resonates is the soul-shattering pain that both DiCaprio and Danes communicate. Friar Laurence’s “These violent delights have violent ends” warning is revealed as an omen. Romeo’s gasping breaths and panicked eyes as he realizes, while dying, that his wife is alive; Juliet’s sole broken sob as she slides her wedding ring back on her finger before picking up Romeo’s gun. “Romeo + Juliet” continues past this scene, with the Capulets and Montagues both appropriately shamed for their actions, but regret has never brought anyone back to life.

“We were born to die.”

—Capulet, “Romeo + Juliet”

So much of what Luhrmann accomplishes with “Romeo + Juliet” is thanks to his purposefully excessive approach to adapting the text: the fast cuts and handheld camerawork unsettling our perspective; the use of water as a means of privacy; and the infectiousness of the soundtrack, in particular Quindon Tarver’s cover of Prince’s “When Doves Cry,” which does exactly what the film is doing: update a classic through fresh eyes. Luhrmann would use these methods over and over again throughout his ensuing filmography—2001’s “Moulin Rouge!”, 2008’s “Australia,” and his reunion with DiCaprio for 2013’s exquisite “The Great Gatsby”—but “Romeo + Juliet” stands apart for the immensity of Leguizamo and Perrineau’s performances, the passionate commitment of DiCaprio and Danes, and how the film’s entire ensemble captured the simmering lustfulness, reckless willfulness, and inclusive possibility of fair Verona.