There are many Orson Welles, and each one of them contains multitudes. There’s the boy genius who directed Citizen Kane at just 25, a film regularly cited as The Greatest Ever Made. There’s the radio phenomenon who brought national panic to the United States with his broadcast of HG Wells’ ‘War of the Worlds’. There’s the theatrical impresario whose Mercury company staged some of the defining productions of the 20th century. There’s the European exile, hustling his way across the continent in a bid to fund an ever-increasing slate of would’ve-been, should’ve-been, weren’t-to-be features. And there’s the bon vivant talk show guest, a man voracious in his appetites – not least for the art of self-mythologising.

Welles was a filmmaker defined as much by his bad fortune as his good. The unprecedented creative control he exerted on Citizen Kane effectively began and ended with that first triumph. His second film, The Magnificent Ambersons, was butchered by the studio in his absence (Welles’ original cut remains cinema’s holiest of grails), a pattern which continued for the rest of his career. Reconstructions of his unfinished works have, to varying degrees of success, been surfacing for decades, every one of them an event. The Other Side of the Wind was completed by Netflix as recently as 2018, with the adjacent interview project Hopper/Welles currently touring the festival circuit ahead of a 2021 release.

Some unrealised projects, like his 1970 nautical thriller The Deep (later filmed by Phillip Noyce as Dead Calm), exist only in fragments and are occasionally screened by the Munich Film Museum. Others, like It’s All True, a travelogue Welles was filming in South America while Ambersons was being gutted, are viewable only within the context of documentaries about their creation.

Critics and biographers continue to scavenge for a ‘Rosebud’ that might serve as a key to unlocking the myriad mysteries of Orson Welles; his only peer when it comes to sheer volume of word count on his life and work being Alfred Hitchcock. For the most thorough biographical account of his life, Simon Callow’s three volumes – with a fourth on the way – are essential, while Peter Bogdanovich’s legendary interviews were collected into ‘This is Orson Welles’, a single volume edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum in the early ’90s. For critical insight, pick your poison from the earliest volumes by Peter Cowie and Joseph McBride to the remarkable accounts of the makings of Kane and Ambersons by Robert L Carringer.

What follows is an attempt to highlight everything that’s readily available in the Welles filmography. Of course, ranking the works of one of the great titans of cinema is probably a fool’s errand, and one even the three of us putting this together couldn’t easily agree upon. So take it either with a pinch of salt, as an opportunity to tell us your own favourites, or perhaps even as a chance to find some new ones.

20. Don Quixote (1992)

Taken on its own terms, the slipshod 1992 reconstruction of Welles’ attempt to bring ‘Don Quixote’ to the screen is not without its modest pleasures. A team which included perennial Spanish trash-man Jesus Franco (who had worked as second unit director on Chimes at Midnight) fused together some 45 minutes of promising existent footage with a doc that Welles had made about Pamplona and ended up with a rather misaligned approximation of the late maestro’s vision. What kills it as a serious fragment of Wellesiana is the awful dubbing and voiceover, which make it instantly feel like you’re watching a salvage job.

Meanwhile, the editing is purely functional rather than expressive or poetic – it’s an attempt to practically piece together the natty vignettes of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza discovering the contraptions of the modern world with a mix of bemusement and awe. It’s certainly worth sitting through if you’re a Welles completist and have two hours to spare, although things do get a bit gruesome when some late-game padding includes skulls being crushed in the ceremonial bull run, followed by a protracted bullfight. Word around the campfire, though, is that the untainted footage is really something special – currently screened only at cinematheques and not available on any form of home video. David Jenkins

19. Too Much Johnson (1938)

The deliciously-titled Too Much Johnson was thought to be lost for the best part of 70 years when a print was discovered in an archive in Pordenone, Italy – the location of a feted annual silent film festival. It was originally made to serve as a visual accompaniment to one of Welles’ Mercury Theatre productions, but due to lack of resources it never saw the light of day. The film itself is a silly, knockabout comedy which also serves as an introduction to the diverse talents of leading man and Welles acolyte Joseph Cotten.

It plays like a pastiche of a Harold Lloyd or lesser Buster Keaton runaround, as Cotten’s Augustus Billings dashes around various New York locations (park, dock, factory) and there are light pratfalls a-plenty. When news of this unearthed oddity arose, some perhaps thought it might offer some crooked key to Welles’ estimable canon, but the sober reality is, it’s more a quaint little work-out with pals that just about fills out its modest, 40-minute runtime. DJ

18. Journey into Fear (1943)

As part of Welles’ deal to make The Magnificent Ambersons, he was required to star in a quickie for RKO alongside members of his Mercury theatre company. Working from a script written by his Kane and Ambersons co-star Joseph Cotten (and an uncredited Welles) and shot concurrently with Ambersons, the film was ostensibly directed, for the most part, by the efficient Norman Foster, best known for his work on the popular Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto series.

While enjoyable enough, it’s an unremarkable Hitchcock knock-off, with just enough Wellesian touches to deduce the actor’s presence – at least in part – behind the camera as well as in front. Welles’ brief role, setting the ship-bound espionage plot in motion, sees him heavily made-up as Colonel Haki, head of the Turkish secret police and subject of “a legend he can drink two bottles of whiskey without getting drunk.” Welles directed his own scenes quickly and in broad strokes, fulfilling his contractual obligations before setting off to South America to make the ill-fated It’s All True.

One certainly couldn’t call Journey Into Fear a Welles joint proper, and even as an actor he appears content to let his Stalin-esque make-up do most of the work. If there’s tension, it’s not of the requisite dramatic variety, but lies in the schizophrenic directorial handshake between journeyman Foster and the half-arsed expressionist impulses of Welles’ day-player. Whatever further merits it may have had, RKO stripped it down to 68 minutes of its action essentials regardless. One for completists. Matt Thrift

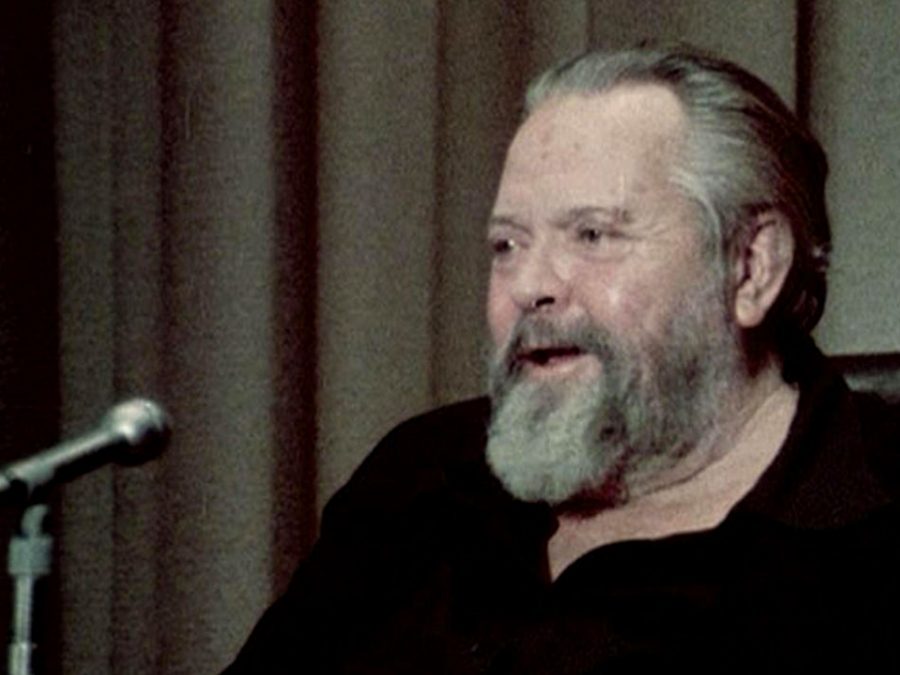

17. Filming The Trial (1981)

This low-grade feature-length director’s commentary was filmed live (by Welles’ final cinematographer, Gary Graver, who previously lensed F for Fake and Filming Othello) at the University of Southern California immediately after a screening of The Trial. Satisfied with the outcome of Filming Othello, Welles intended to produce several more essay films covering what he considered to be his crowning achievements. In this case, however, he never got around to editing the footage, passing away four years later. Yet even in its raw state there’s something undeniably compelling about Filming the Trial, with Welles enhancing his reputation as a raconteur par excellence while fielding questions on everything from the artistic and logistical considerations that went into making the film, to its intended meaning, to his general outlook on life and the movies.

Ever the consummate magician, Welles relishes the opportunity to talk up his own technical game without ever revealing how the film’s greatest tricks were achieved. For the most part, though, he’s a generous interview subject; his jocular, self-deprecating manner instantly enamours him to the crowd, who hang off his every word and greet each zinger more enthusiastically than the last (when pushed on the status of his unfinished Don Quixote: “It will be finished […] when I feel like it. And when it is released, its title is going to be ‘When Are You Going to Finish Don Quixote?’”). A frisky, frequently insightful addendum to one of Welles’ masterworks – who knew he was such a big Al Pacino fan? Adam Woodward

16. The Stranger (1946)

Welles the lead actor rarely allowed himself to be outmuscled, but in sparring with the great Edward G Robinson in 1946’s The Stranger the hotshot multihyphenate finally met his match. The film sees Robinson play a seasoned criminal investigator fishing for a Nazi fugitive who is assumed to be living under an alias somewhere along the Eastern Seaboard. Using a former associate of the notorious war criminal as bait, the inspector is led to smalltown Connecticut where a debonair prep school teacher named Charles Rankin (Welles) raises his suspicion.

Containing actual documentary footage of the Holocaust (the first Hollywood picture to do so), this shifty, suspenseful noir consolidates Welles’ preoccupation with the banality and duplicity of evil – specifically, how it worms its way into everyday life, often in unexpected and insidious ways. For all its high dramatic tension – not least the climactic ladder-based set-piece inside a clock tower – the film’s most memorable images are comparatively mundane, such as Welles’ wanted man idly doodling a Swastika while calling his unsuspecting wife from a payphone. Holds the distinction of being the only film Welles made during his lifetime to turn a profit, and is perhaps the most readily available to watch, having entered into the public domain when its copyright expired. AW

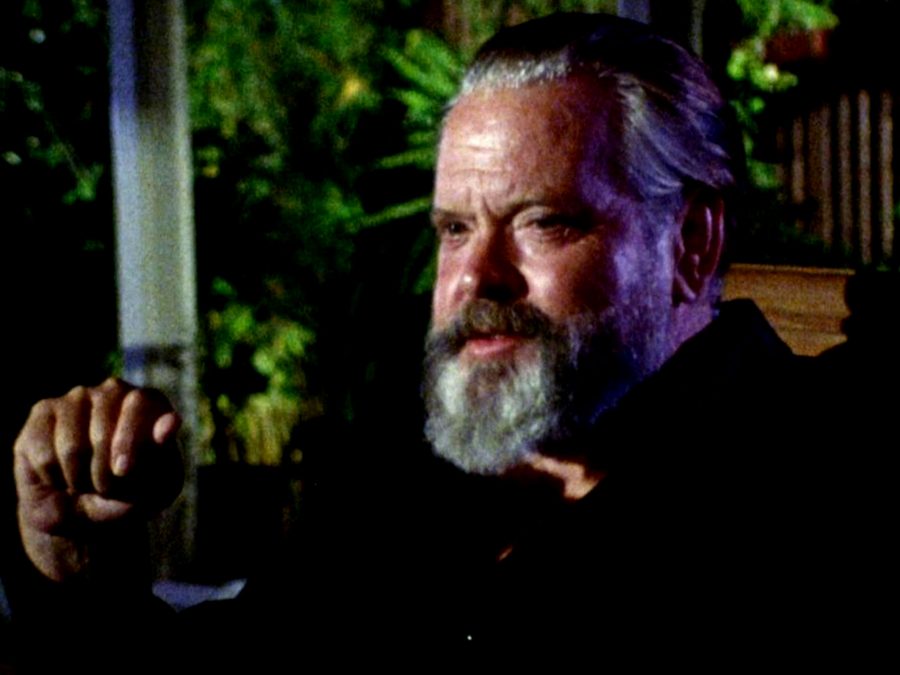

15. Filming Othello (1978)

Six years before the first director’s commentary appeared on Criterion’s laserdisc edition of King Kong, Welles fashioned the first in what was intended as a series of feature-length studies of his films. Only Filming Othello was completed, becoming the last Welles picture to be released during his lifetime.

By this point, Welles was a well-established raconteur, so it’s a pleasant surprise to find so much more by way of close textual analysis than anecdotal frivolity. It begins with Welles at his Moviola *“The last stop between the dream in a filmmaker’s head and a public to whom that dream is addressed”) backed by an assortment of theatrically-lit, potted vegetation, with Welles monologuing on Othello’s stylistic vocabulary as sequences from the film play out: “The grandeur and simplicity are the Moor’s The dizzying camera movements, the tortured compositions, the grotesque shadows and insane distortions – they’re of Iago, for he is an agent of chaos… The longer we’re in Cyprus, the more the involuted Iago style triumphs over the heroic and lyrical Othello style.”

Welles the critic, spilling the guts of his cinematic mysteries? Not quite. It’s been pointed out that Welles, that slippery, self-guarding grifter, is simply passing off the words of writer Jack Jorgens – whose critical study Shakespeare on Film was much admired by the filmmaker – as his own. Nonetheless, it makes for an essential companion piece to Othello, as funny and self-deprecating as it is formally and thematically instructive, with some real chuckles to be had from the home-made expressionist lighting schemes, seemingly fashioned from whatever lamp is to hand; including an especially fun why-the-hell-not perspective shift that stares up at Welles from the floor beside his chair and looks like it was shot by the cat. MT

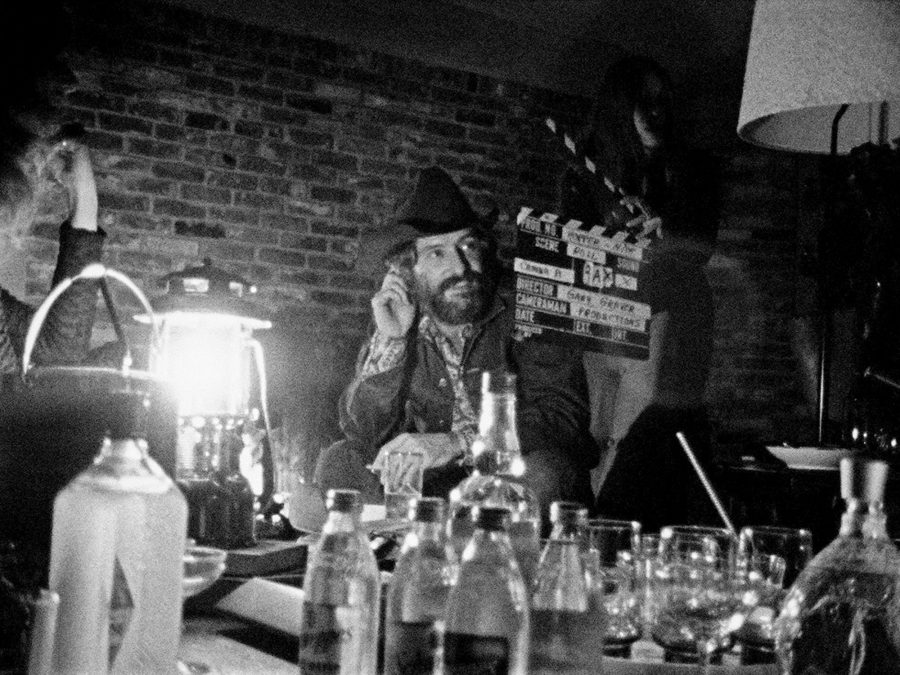

14. Hopper/Welles (2020)

The boy wonder of Hollywood’s golden age interrogates his New Hollywood heir in this fascinating document of a meeting that took place exactly 50 years ago, in November 1970. Dennis Hopper had flown in from New Mexico where he was shooting The Last Movie – his follow-up to the cultural phenomenon Easy Rider released the previous year – to meet with Welles, who was at work in Los Angeles on The Other Side of the Wind. Recovered from the hundred hours of recordings Welles made for that picture, it’s a fantasy-dinner-guest bonanza, seemingly shot – and best consumed – at the witching hour in inky black and white; 130 minutes of two iconoclasts shooting the breeze and digging deep into their respective cinematic and political visions.

Welles doesn’t appear on screen, the two cameras never leaving Hopper’s face, effecting a quasi-Warholian intensity of portraiture as the younger filmmaker nervously puts away countless G&Ts while mounting a barely adequate set of defences to Welles’ pointed, escalating provocations. It begins harmlessly enough, with Hopper waxing lyrical on Resnais and Antonioni (Welles: “I didn’t like L’Avventura even before I fell asleep”), but there’s a sense, for all Welles’ encouraging charm, that an attack – or at least a good prod – is ever-imminent, something further complicated by his slipping in and out of the ultra-conservative Jake Hannaford character played by John Huston in The Other Side of the Wind.

Conceived as an improvisatory exercise to support Welles’ feature, it’s at its most illuminating when the masks and defences of both parties slip, while also serving as a further entry in Welles’ pantheon of great men confronting a lost past through a vessel of the future. MT

13. Othello (1951)

The most notorious of Welles’ protracted productions, it’s a miracle we have his adaptation of Othello at all. In contrast to his Macbeth, which he shot in just three weeks, his second Shakespeare film took the best part of four years to complete, with Welles constantly running out of money during a shoot that took him across Europe and Morocco.

The first feature made during his ‘European period,’ the film is antithetical to Macbeth, whose claustrophobic, psychological containment is swapped out for striking expressionist compositions, grand visual gestures that in many ways work against the verbal and gestural nuances of the great play. Eye-popping in its hallucinatory design, it demonstrates Welles’ capacity to do a lot with a little. When it came to shoot the murder of Roderigo, the costumes hadn’t arrived, so Welles stuck the cast in towels and pumped incense into a fish market playing the role of a steam-filled Turkish bath.

Welles was always embarrassed of his skills as an actor, an issue only amplified by the necessity for blackface make-up to play the Moor. It’s not one of his great performances, which perhaps goes some way to explain the distracting primacy of his visual schemes. It remains cinema’s greatest Othello, but among Welles’ Shakespeare joints, it can’t match the theatrical cohesion of Macbeth or the heartrending pathos of Chimes at Midnight. MT

12. Macbeth (1948)

A full decade before he mounted the first major Hollywood adaptation of Macbeth in the age of synchronised sound, Welles staged a groundbreaking reimagining at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, New York, employing an all-Black cast and relocating the story to Haiti. If this radical (read: risky) production was anything to go by, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Republic Pictures were hesitant to cut Welles a blank cheque – especially given the Bard was hardly a box office banker at the time. Reluctantly, Welles conceded and set about constructing his cut-rate prestige pic, borrowing stock costumes and using vacated soundstages usually reserved for cowboy movies.

The studio’s skepticism was well-placed, at least in a financial sense: Macbeth was not a commercial hit on its initial release, only becoming modestly profitable when it was re-released in 1950 after Welles had been ordered to cut two reels and re-record the actors’ dialogue, sans Scottish accents. Still, it stands today as arguably the boldest filmed version of Shakespeare’s play. There’s even an argument to be made that the limitations imposed on the director actually aided his endeavour – the tightly-framed castle set on which the majority of Macbeth was filmed, designed by Welles and Dan O’Herlihy (who also stars as Macduff) and cloaked in thick Caravaggio-esque shadow by DoP John L Russell, certainly adds to the general feeling of claustrophobia and despair.

Wonky Scotch lilt aside, Welles gives a typically commanding performance in the central role, bringing more than a touch of Tinsel Town swagger to Shakespeare’s power-thirsty Thane. Instead of the tragic anti-hero traditionally portrayed on screen, Welles offers something decidedly less hubristic; his would-be king is more conflicted and impulsive, and never really seems like he’s thought out his next move. Though largely faithful as an adaptation, this along with several other notable narrative deviations make this moody, monochromatic chamber piece a Macbeth entirely of Welles’ invention. AW

11. The Fountain of Youth (1958)

For the most concentrated dose of Welles at his most experimental and playful, turn to this miniature marvel he made for television in 1956. Originally conceived as the first episode of an intended series, needless to say the network ran a mile when Welles delivered his breathlessly inventive collage of ideas that thumbed its nose at anything resembling formal precedent. It aired just once, two years later in 1958, and won a Peabody Award for creative achievement.

Pitched, thematically at least, somewhere between the Faust legend and The Picture of Dorian Gray via Howard Hawks’ 1952 film Monkey Business, the comic tale – Welles called it his only comedy – concerns an elixir that promises youthful rejuvenation to those who imbibe it. Welles himself presents and narrates, though either term understates his intrusion into the tale itself – not for nothing does he begin by telling of Narcissus with an impish glint of recognition.

Constructed via a montage of still images, rear-projection, lighting and sound effects, The Fountain of Youth shows Welles the magician at work, crafting illusionary transitions and staggering visual effects seemingly on the fly – not quite, the shoot lasted a mere four days. It’s the missing link between his dramatic features and the puckish prestidigitation of F for Fake. Essential viewing, and (currently, at least) available on YouTube. MT

10. The Other Side of the Wind (2018)

Streaming giant Netflix have made a couple of bold plays for cinephile credo, but none was more outlandish (and able to cause the naysayers to demure) than their commitment to restoring and releasing Welles’ lost, latter-day masterpiece. In tantalising press snippets, Welles himself touted this illusory film as his attempt to forge a new kind of cinema, and the result is a radical, mesmerising, audacious and, at moments, truly sublime spectacle of gaudy intrigue. The superlatives are necessary here, because the film itself devilishly eludes simple description: it’s a party movie with an immersive experiential bent, captured in its lightning-quick editing, and dialogue which darts at you from every which way.

At its core is a passive duel between an ageing maestro (John Huston) and his commercially successful pretender (Peter Bogdanovich) and Welles is once more interested in the question of the legibility of an artistic legacy and how questions of imposed identity arise when we die. It’s a big, gaudy Euro art film that’s an exemplar of its era, but also lightly mocks the directorial titans it claims to admire – most notably Antonioni and Felini. DJ

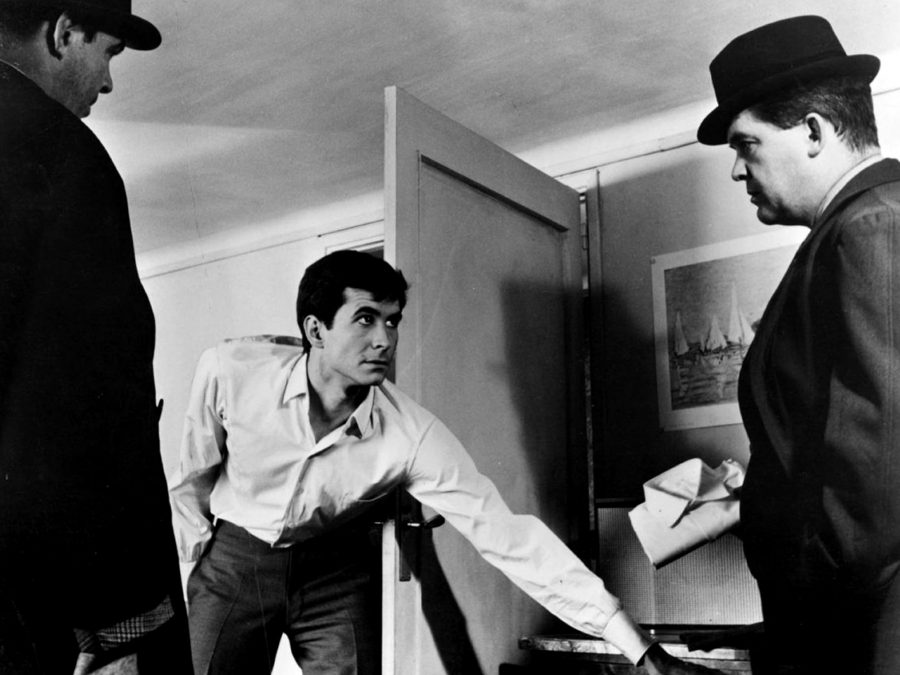

9. The Trial (1962)

“Why am I always in the wrong without even knowing what for or what it’s all about?!” Anthony Perkins, still fresh in audiences’ minds as the mother-loving antagonist of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, has the tables well and truly turned on him in Welles’ elusive procedural, playing the unwitting victim of a sinister and apparently surreptitious plot. Like Franz Kafka’s posthumous novel (which Welles relocates to the 1960s), The Trial is a dense, elliptical psychodrama that contains a scathing critique of the soul-draining drudgery and tyrannical bureaucracy of modern society.

It starts with Perkins’ lowly but ambitious bank clerk, Josef K, being arrested in his apartment for an unspecified crime. What ensues is a maddening cycle of doublespeak and skulduggery, as K tries to navigate the corridors of power – visualised as a cavernous courtroom that backs onto a similarly vast open-plan office, where the incessant clatter of adding machines is almost deafening – and seize control of his destiny. As his case edges towards its grim, inevitable conclusion, K – having been denied the protection of one of the fundamental maxims of law; a person must be presumed innocent until proven guilty – slips deeper into a state of paranoid hysteria.

Welles called this the best film he ever made. Well, we’d happily lose the allegorical prologue (narrated by Welles, natch), which too conveniently establishes a thematic framework for the viewer – but it’s certainly in the top tier. The Trial’s baroque production design, expressionistic lighting, disorienting low-angle camerawork and enigmatic supporting performances (including Welles himself as The Advocate; stealing every scene he’s in while barely get out of bed) make it essential viewing for any serious cineaste. Up there with Repulsion and L’Eclisse as one of the most atmospheric and subversive European films of the early ’60s. AW

8. The Lady from Shanghai (1947)

This is yet another jaw-dropping exercise in creative idiosyncrasy that teeters on the brink of insanity and which was duly mangled by Welles’ studio overseers (Columbia). A pointedly counterintuitive deconstruction of classic film noir, the film sees the maverick writer/director take everything audiences knew and loved about this cherished genre and malign it in some way. Could be a courtroom sequence which descends into a Dada-esque farce with a criminal attorney asking questions of himself, or maybe it’s the fact that its femme fatale (Rita Hayworth) sports tightly cropped locks instead of the traditional cape-like wall of blonde hair.

Welles himself sports an acrobatically bold Irish brogue as ruminative poet-warrior Michael O’Hara, as he is spirited away to the West Indies on a yacht for a bizarre pleasure cruise with Hayward’s ice maiden Rosalie, her eccentric legal eagle husband Bannister (Everett Sloane), and a grotesque, heavily-perspiring henchman named George Grisby (Glenn Anders). For the first half of the film, there are merely hints that something is amiss and that Michael is being played.

The full extent of the ultra-contrived grift then becomes apparent, and the film jack-knifes its way through a series of ever-more-absurd and complex revelations. Still, story aside, the old Welles magic is there in spades, from the quasi-erotic way he shoots Hayward as a fallen goddess, to his nutty decision to film a major romantic clinch in a public aquarium. And that fairground finale, with its hall of mirrors stand-off, remains one of the much-imitated/never-equalled stylistic pinnacles of the medium. DJ

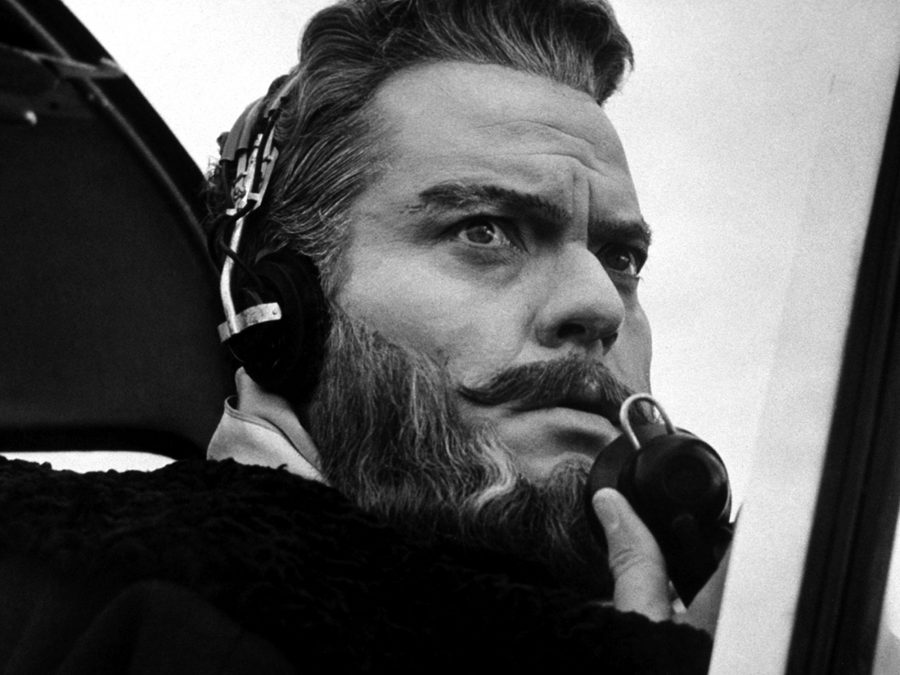

7. Mr Arkadin (1955)

If there were an award for the greatest film with the worst central performance, then Mr Arkadin (aka Confidential Report) would be in the running. The perpetrator is actor Robert Arden, a yapping Anthony Quinn lookalike who plays the role of a globetrotting hustler-cum-mega patsy as if he has absolutely no idea who Orson Welles is and what he has made previously. And yet, his pitiful, TV movie-esque turn only ends up making the tiniest dint on the pleasure elicited from this extraordinary, thriller-adjacent riff on Citizen Kane, which also mixes in the elements of political conspiracy seen in Carol Reed’s The Third Man in which Welles played the dastardly, be-cloaked rapscallion Harry Lime.

The big man himself plays Gregory Arkadin, a hulking mitteleuropean shitbag with a supervillain-styled asymmetric beard who hires Arden’s Gus Van Stratten to uncover who he was prior to suffering from a sudden bout of amnesia. As the investigation plays out, both parties tangle over the affections of Arkadin’s capricious daughter Raina (Paola Mori), and it all arrives at an unforgettable, knuckle-gnawing finale involving the mystery of a bi-plane flying without a pilot. The film was made relatively cheaply and was filmed at various locations across Europe, though mainly Spain. Even more than some of the other ignoble hatchet jobs of yore, Arkadin suffered the wrath of commercially-driven producers and it’s believed that no existent version is quite the same as the director’s original, untainted vision. DJ

6. F for Fake (1973)

If you’ve ever been the victim of a magic trick, or witnessed an illusion up close, the classic response is, “Show me again!” A similar impulse comes to light when watching Welles’ dazzling feature swansong, F for Fake, a pseudo-documentary which professes to explore the notion of authenticity in art. When it finishes, you can’t help but feel you’ve been intellectually trounced, and you absolutely need to work out how you fell for such a ruse. So you rewind, and watch it again. This happens every time I see this movie, and still I’m not sure I completely understand where the sleight of hand takes place.

Welles plays a showman magician iteration of himself, regaling viewers with the story of master Ibizan art forger and bon viveur, Elmyr de Hory, while mixing in the travails of author Clifford Irving who fabricated a biography of Howard Hughes. The film is a delicious provocation delivered with the kind of formal Chutzpah we’d expect from Welles when he is given ample time, control and resource. You could probably write a book on the editing alone. It asks whether truth has any real bearing on the value of a piece of art, and whether lies are a necessary part of the mythos behind any artist and their work. It also questions why we’re unable to accept art at face value, in a bubble and wholly decontextualized – if it’s good, then it’s good, right? DJ

5. The Immortal Story (1968)

It’s fascinating to compare early Welles with late; to contrast the dynamic, everything-or-nothing rush of youthful zeal with the still simplicity of age. It’s particularly useful here, given the way The Immortal Story holds up the impotence (both figurative and literal) of old age against the vigour of youth. It’s a film that speaks loudly to questions of artistic control – to authorship, even – and it’s not hard to see why Welles’ was drawn to the novella by Isak Dinesen (the nom de plume of Out of Africa novelist Karen Blixen).

Welles plays the decrepit Mr Clay, a wealthy merchant in Macao who sets out to recreate a story passed among sailors of a youth hired to impregnate an old man’s wife. The four principals all know the tale, but Clay – hater of stories, pretence, prophecies – wants to orchestrate its happening in real life, “So that one sailor can truly tell it, from beginning to end, as it actually happened to him.”

Thus Clay hires his cast and takes on the role of director – “to demonstrate his omnipotence, to do the thing that cannot be done” – as Welles constructs his most theatrical of pictures, a chamber piece pregnant with ritual and repetition across a slender running time of just 58 minutes. There’s little stylistic showboating here, just Welles’ uncanny, meditative schemes, essential in their clarity – at least until the moment Jeanne Moreau’s Virginie prepares for the story’s consummation, and the rapture of the final, defining moment itself, which, in Welles’ view, can only lead to death. Clay’s tale is told, the story is finished, and so the sailor leaves. “You’re so sure this comedy of his will be the end of him?” Virginie asks, “I’m sure of it too.” MT

4. Touch of Evil (1958)

The film career of Orson Welles is a case study in the negative attributes of what many like to refer to in the pejorative as “studio interference”. That’s not to say that a producer or studio head’s creative interventions haven’t saved many a potential flop from box office ignominy, but with Welles, it was like everything he touched was not quite right for the conservative, unrefined tastes of the general audience. Maybe this was all a long-game revenge for his peacocking prodigy phase around the production of Citizen Kane? It means that the best version of 1958’s Touch of Evil that we have today is one reassembled from notes contained in a detailed 58 page memo written to Columbia Pictures by Welles in which he said, to paraphrase, please god don’t butcher my film.

In it he plays the corpulent, crooked police captain Hank Quinlan, who flaunts his crackshot investigative intuition while having toadying cohorts plant false evidence to seal a conviction. Set in the fetid Mexican border town of Los Robles, Touch of Evil essays corruption (and the power it fosters) as personal addiction, with Quinlan’s reign of terror eventually scuppered by Charlton Heston’s industrious Mexican lawyer, Vargas. Formally, the film combines stellar showpiece sequences with editing that flits between multiple subplots and various eccentric characters.

Absolutely key to the film’s greatness, however, is the inclusion of Tanya (Marlene Dietrich), a laconic madame and fortune teller who is, in her own way, the embodiment of Hank’s lost innocence. Her spectral presence is signposted by Henri Macini’s repeated barroom piano theme, and she rounds out the film by uttering perhaps the greatest line of dialogue in all cinema. DJ

3. Citizen Kane (1941)

Let’s get one thing straight: Citizen Kane is not the best film ever made. It’s not even the best film Orson Welles ever made, though it is unquestionably his most influential. As far as we’re concerned, rankings of filmographies (yes, even the one you’re reading now) are inherently arbitrary and reductive exercises, and the GOAT crown is a burden which no single work of art should be forced to bear. But if we are to furnish Welles’ monolithic masterpiece with further praise, allow us to turn your attention towards one of the film’s unsung stars.

One of the few principal cast members who was not part of Welles’ regular acting troupe, the Mercury Players, Dorothy Comingore is by some distance the biggest revelation as Kane’s second wife, Susan Alexander. Her combination of coyness and vulnerability makes her the perfect foil for Welles’ cynical, self-aggrandising publishing tycoon. Indeed, their initial meet-cute, which feels like it’s been plucked from a classic Hollywood romantic comedy, is the film’s most disarmingly tender scene. Like Kane, Susan ultimately cuts a lonely figure, and from the first time they lock eyes we get the sense that she sees him for precisely who he is. AW

2. Chimes at Midnight (1965)

More often than not, Welles leads with his camera. Certainly in Citizen Kane, it’s the frame, followed by the cut that commands his formal charge. Such authorial dominance is tempered in The Magnificent Ambersons, and all but absent from Chimes at Midnight, Welles’ defining late, great film. “Everything of importance should be found on the faces,” Welles said of the film, “On these faces that whole universe I was speaking of should be found.” It’s a film led by its subjects and which lives in its close-ups, and no face fills the frame like that of Welles’ own Falstaff.

Taking bits and pieces from the two parts of Shakespeare’s Henry IV plays, along with his Henry V and Richard II, Chimes at Midnight repositions the voracious Falstaff as its central, tragic figure; he of Bacchanalian appetites for life and wholly lacking in moral filter. It’s the role Welles – an often limited actor – was born to play and spent a lifetime growing into. So often casting (himself) as men of status or mystery, usually hidden behind prosthetics, here we find him at his most nakedly vulnerable, none more so than in the film’s climactic sequence. Prince Hal’s rejection of his old friend upon ascension to the throne might just be the greatest scene Welles ever filmed, with which six words – “I know thee not, old man” – see a universe shatter.

It’s a film about father figures and betrayal, about competing impulses and the sacrifices required to attain power – themes close to Welles’ heart; a film so full of life and empathy it’s almost fit to burst. It also features the greatest battle scene ever committed to celluloid, five minutes or so at the centre of the film shot, as was Welles wont, in a park in the middle of Madrid. Not that you’d know it from the sheer scale of the spectacle he captures, so breathtaking in its editing. Unseen for many years, it’s not just the greatest Shakespeare adaptation in cinema, but one of the great, great films. MT

1. The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)

Welles’ great themes – of lost Edens and falls from greatness – find their richest realisation in his second film. Adapted by Welles from the Pulitzer-winning novel by Booth Tarkington, The Magnificent Ambersons essays the decline of an aristocratic family, usurped by a rise of industry emblematised in the motor car in which the forward-looking Eugene (Joseph Cotten) cavorts around town.

It’s fitting that a film so concerned with an idealised view of a past that never truly existed would itself be subject to similar, might-have-been idealisation, given its butchery at the hands of RKO, the same studio for whom Welles had made Citizen Kane just a year earlier. Shorn of 43 minutes, with scenes re-shot against its directors wishes – including an especially egregious ‘happy’ ending – Welles’ cut of the picture screened just twice for preview audiences before its consignment to the smoke of history.

And yet… How can a film so cruelly maimed still stand among Welles’ greatest achievements? There’s a school of thought that the cutting of the film – at its most violent in the second half – mirrors the decline of the Amberson family. A suitably romantic notion, given the Ambersons’ inability to realise that everything they grasp for has already slipped through their fingers.

The magnificence of Ambersons doesn’t rely on a stretch of the imagination, it remains in spite of its impairments – crippled but not lobotomised. The hothouse, Oedipal fervour that induces the fall of the pompous George Minafer (Tim Holt) remains intact, as does the decaying grandeur of Welles’ imagery; a tattered decadence held in counterpoint to the dire persistence of an encroaching moral and fiscal rot.

The ironic detachment that served Citizen Kane remains, largely in Welles’ narration, as in the staggering opening scenes that chart the family’s rise – accompanied by a greek chorus of chattering townsfolk – while already sounding its eulogy. It’s but the first of the film’s many extraordinary sequences: the snow-bound car ride and its glorious iris out; the party scene, even with its master shot hacked to pieces; the montage of dilapidated houses as George walks the deserted streets; Agnes Moorehead’s collapse – one of the greatest performances in Welles’ cinema. The list goes on and on.

It’s unlikely we’ll ever see The Magnificent Ambersons as Welles intended, but for the pungent, vividly inhabited 88 minutes we have, we’re graced with a wounded elegy, not just for a lost time and place, but for its very self. MT

What are your favourite Orson Welles films? Let us know @LWLies

The post The films of Orson Welles – ranked appeared first on Little White Lies.