No Way Back: How They Shot the Bridge Scene in ‘Sorcerer’

Welcome to How’d They Do That?, a bi-monthly column that unpacks moments of movie magic and celebrates the technical wizards who pulled them off. This entry explains the making of the scene in William Friedkin’s ‘Sorcerer’ where two enormous trucks cross a rotting suspension bridge.

William Friedkin‘s nihilistic opus may share its name with “Sorcerer,” one of the two hulking transport trucks that propel the film’s nail-biting second half, but the film’s ultimate fate took after the second vehicle’s namesake: “Lazarus.” Despite its commercial and critical death in 1977, Sorcerer was later revived, in large part thanks to Friedkin’s efforts to ensure the film’s survival on home video. Today, many regard the film as a grueling, beautiful, and underappreciated triumph.

The film follows four criminals who have sought refuge in a remote village: Jackie Scanlon (Roy Scheider), a getaway driver marked for death; Victor Manzon (Bruno Cremer), a disgraced investment banker; Kassem (Amidou), a politically-motivated terrorist, and Nilo (Francisco Rabal), an assassin.

One day, a nearby oil rig explodes, sending a turret of fire scorching into the sky. To stifle the flames, the oil company needs explosives. And the only dynamite available is rotting in a shed 218 miles away, sweating volatile nitroglycerine that could explode with the slightest jostle. The only way to transport the stuff through the hostile terrain is by truck. Incentivized by a financial reward that could pay their way home, the four men volunteer for the job.

Well into their journey, the two trucks come to a crossroads. Despite taking different paths, fate ultimately dumps them both at the same place: the bank of a raging river. A dilapidated bridge lies ahead, stitched together with loosening rope and soggy, splintering wood. Wind gusts violently, spraying torrents of rain in every imaginable direction.

The task is clear but impossible: to cross this bridge, in these trucks, and to make it to the other side alive. The Lazaro arrives first and incrementally begins its agonizingly slow crawl. Nilo guides Scanlon as the bridge buckles and tilts, cracking under their weight. Each sway is a threat, but somehow they make it across. And before you can catch your breath, Sorcerer arrives to attempt the same treacherous negotiation. Which it does. Barely.

While studio executives may have found its title misleading, the effect of Sorcerer is, ultimately, an otherworldly one where lumbering metal tanks growl like tigers and purgatory takes on a decaying, desperate aspect. The bridge sequence is no different: it is a spellbinding Sisyphean centerpiece that dangles redemption in the face of assured catastrophe. It is one of the most astonishing sequences ever put to film; cinematic magic performed by an accomplished — if wantonly reckless — sorcerer.

How’d they do that?

Long story short:

While the core of the bridge was made of steel and hydraulics instead of decayed wood and rope, ultimately: they drove a real truck, across a real bridge, over a real river.

Long story long:

Friedkin regularly describes the suspension bridge scene in Sorcerer as the most arduous sequence of his career. Which, considering all of Friedkin’s shenanigans, is saying something. Despite the danger, according to Friedkin, there was no resistance from the crew or the financiers. “That was never an issue,” stresses Friedkin in an interview with The Dissolve. “I must say that while they were concerned, they had total faith in me. And I had a kind of sleepwalker’s certainty that I could pull it off.”

The trucks on-screen were two and a half-ton capacity GMC M211 military transport vehicles, first deployed during the Korean War. Per the Sorcerer press booklet, Freidkin hired a local Dominican artist to decorate the trucks like the haulers he’d seen while location-scouting in Ecuador.

Champion motorcyclist and repeat Steve McQueen collaborator Bud Ekins served as the film’s stunt coordinator — it is perhaps not unrelated that McQueen was Friedkin’s first choice to play Jackie Scanlon. Famously, the main cast did much of the driving themselves. “Every time you see one of the actors in the truck, they are driving,” emphasizes Friedkin in a 2018 interview with Empire. “The fear they show and the caution that they show is real…It’s only in the long-shot sequences that there’s a stuntman.”

Speaking with The New York Times in 1977, Scheider stressed that shooting Sorcerer “made Jaws look like a picnic.” He adds that what you see in the suspension bridge scene is “what really happened.” No optical effects. No rear projection. “Today it would be computer-generated, and it wouldn’t be life-threatening,” supposes Friedkin, correctly.

The bridge itself was the creation of legendary production designer John Box, whose previous credits include Laurence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago. The bridge was originally constructed and assembled in the Dominican Republic at a cost of one million dollars, a price tag justified because this was, after all, the big set-piece of the film. As Friedkin tells it, the river was reliably deep during the months they planned to shoot.

And the river dried up. The studio executives suggested that Friedkin scrap the scene for something less sophisticated. But Friedkin, of course, ignored them and immediately sent Box to find a different river. Box found a promising alternative near Tuxtepec, Mexico. The section of Papaloapan River had a similar topography and deep rushing waters that “had not diminished in living memory,” as Friedkin puts it. The bridge was dismantled, shipped to Mexico, and re-anchored. And then, like a cosmic joke, the Papaloapan started to dry up too.

Without the time or money to find another river, the production had to make the Papaloapan work. In addition to clever camera angles to disguise the true depth of the river, the production employed a series of mechanical effects: piping and pumping equipment re-routed the water and the river was dammed to inflate the current; wind machines and giant hoses gave the impression of a monsoon, and a massive sprinkler system created an artificial rainstorm that obscured the low water levels. Because the rain required cloud-coverage, they could only film in the morning and the evening with a hiatus in between.

A carefully concealed hydraulic system controlled the movement of the bridge and the trucks. The frayed ropes along the bridge’s sides cleverly disguised supporting steel cables. And, as a precaution, the crew lashed the trucks to the bridge so that as it tilted and swayed, they wouldn’t topple over. In theory.

Despite the cast and crew’s best efforts, the trucks did topple over into the shallow water often with actors and stuntmen inside them. In an interview with Yahoo Entertainment, Friedkin estimates this happened seven or eight times, after which they would repair the damaged section and keep going. According to Ekins’ obituary, right after the frame reproduced on the poster that adorns the Tangerine Dream album, the truck fell in the drink.

In fact, even Friedkin’s truck overturned while he was filming handheld footage over the dashboard. Describing the experience, he explains: “you fell in the water…and you counted yourself lucky that the truck didn’t fall on you or anyone else.” Personally, I like to think that as Friedkin was launched into the water, he recalled the words of Robert Mitchum, who turned down a role in Sorcerer with the following dismissal: “Why would I want to go to Ecuador for two or three months to fall out of a truck? I can do that outside my house.”

In a 2017 interview with British film critic Mark Kermode for Sight & Sound, Friedkin reminds us that during the shoot a good deal of the crew (Friedkin included) contracted gangrene and malaria. To make matters worse, during the reconstruction of the bridge, an undercover Mexican federal officer took issue with the drug use of certain crew members (twenty-some stuntmen, key grips, makeup artists, and special effects artists). Friedkin was forced to send the offenders home to the US — the alternative was that everyone working on the production would be imprisoned.

Ultimately, the bridge sequence took months and a mostly un-budgeted three million dollars to film. But all told: that money, toil, fear, and desperation is up there on the screen.

What’s the precedent?

Sorcerer is the second film based on Gerges Arnaud‘s 1950 French novel Le Salaire de la Peur. The first adaptation, 1953’s The Wages of Fear, is Henri-Georges Clouzot‘s masterpiece. Friedkin is vocal (as ever) that Sorcerer is not a remake of Clouzot’s film but rather is a separate, distinct adaptation of Arnaud’s novel. In fact, another rarely-discussed American adaptation proceeds Friedkin’s: 1958’s Violent Road.

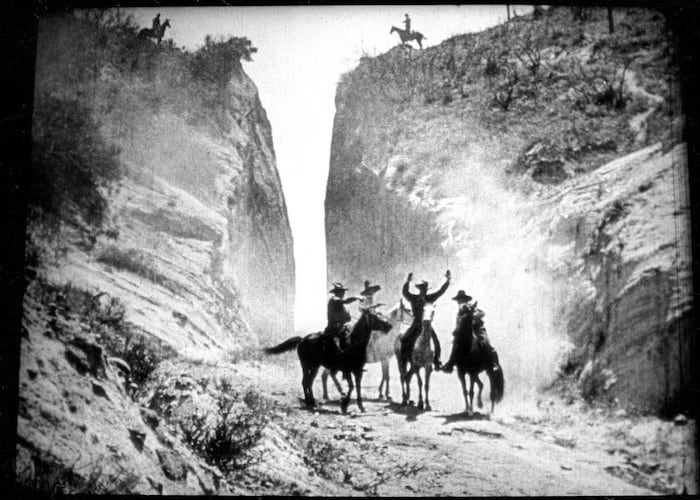

Neither Arnaud’s novel nor Clouzot’s film contains a stormy river crossing. As far as I can tell, it is an original invention of Friedkin and screenwriter Walon Green. If The Wages of Fear has an analog stunt, it is the scene in which the trucks are forced to make a hairpin turn up a mountain using only a rotted-wood outcropping as their support. Like Sorcerer‘s bridge sequence, the stunt makes ample use of clever camera placement and editing to elevate its stakes.

Ultimately, the two sequences (like their two directors) have very different strengths and priorities: one tension, the other dread; one details, the other spectacle. To compare the two of them feels unfair. After all, Sorcerer is not a slow-burning thriller. It is a document, on-screen and off, of a desperate, often arrogant attempt — and only an attempt — to overcome and control the uncontrollable.

In this vein, it makes more sense to seat Sorcerer at the same table as Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), a destructive journey down the Amazon River in search of El Dorado. Or better yet, Herzog’s later Klaus Kinski joint Fitzcarraldo (1982), where a rubber baron’s quest to drag a steamship through the Brazillian jungle reflects the real-life production where Herzog forced his crew to haul a three-hundred-and-sixty-five-ton boat up a hill.

While it premiered two years after Sorcerer, Francis Ford Coppola’s infamously troubled Apocalypse Now (1979) also deserves a mention as a film whose making-of documentary proved a more faithful adaptation of Heart of Darkness than the film itself.

All to say: despite its source material and preceding peers, Sorcerer‘s suspension bridge stunt was born from a very specific and often dangerous attitude particular to the ’70s auteur brats. Namely: that, no matter the risk or the price, the most important thing was to realize the vision.

And if you’re thinking to yourself no one could make a film like that today, Friedkin agrees! “Nor should they,” he states in a 2014 Esquire interview. “I believe today that there is no film and no shot in a film that is worth a squirrel getting a sprained ankle. We were irresponsible in that regard.”

And so, there it is: a perilous if astounding journey, concluding not in redemption, but in too-late understanding.