Found: Cases of ‘Trench Fever’ in Ancient Rome

In October 2018, Davide Tanasi was off the coast of Italy, pulling teeth. His dental patients were 34 Sicilians who had been dead for the better part of 2,000 years. These Roman Christians were buried in the catacombs of St. Lucia in Syracuse, an underground city of some 8,000 dead stretched across an area about the size of the White House. Concealed among their no-longer-so-pearly whites was Bartonella quintana, a bacteria that causes a disease called trench fever, and which arrived in Roman mouths via the guts of lice.

The bacteria—its name a reference to the recurring, five-day fevers it is known to cause—had likely sped some of its hosts to their graves. Tanasi’s subjects were just a few of the infected chronicled in a recent paper tracing the history of trench fever, published in the open-access journal PLOS One.

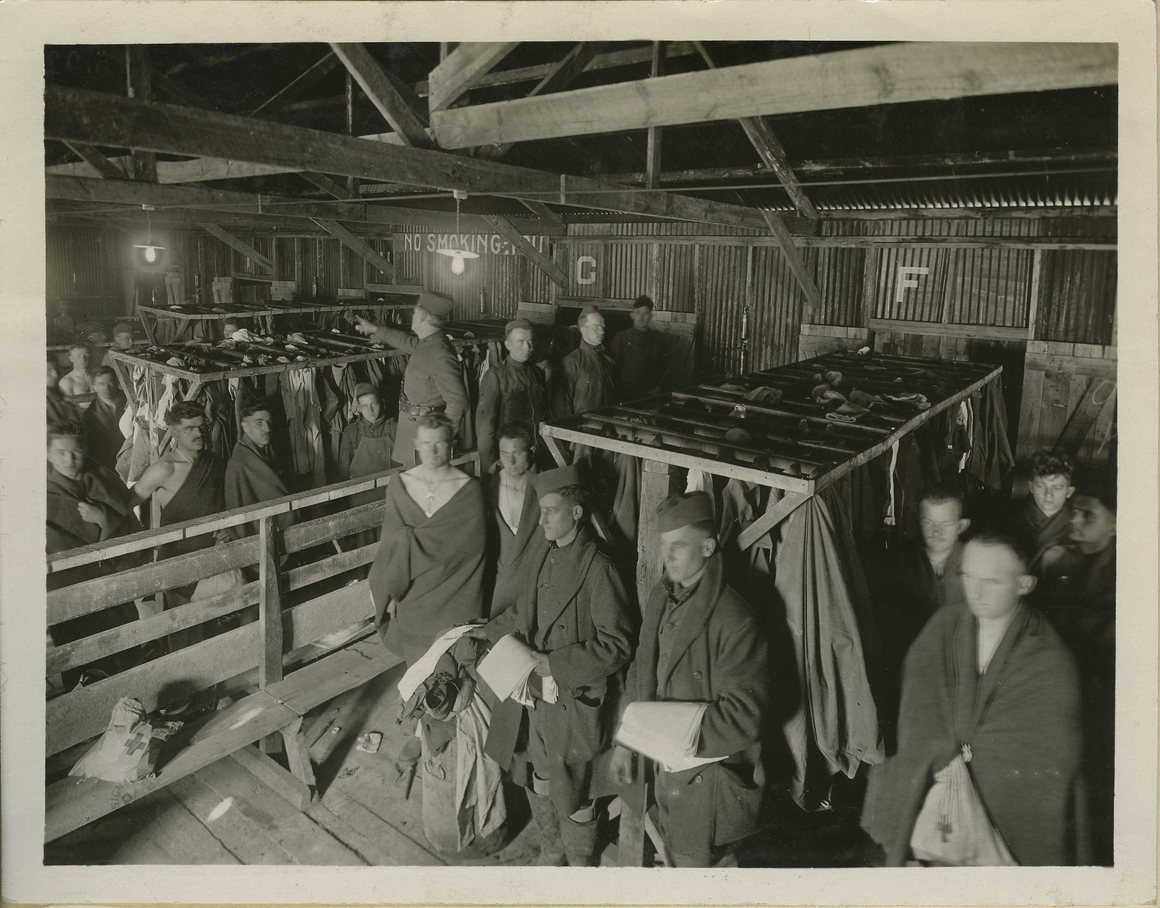

The vernacular name (“trench fever”) was coined for the disease’s prevalence around the unsanitary battlegrounds of World War I. In the trenches, lice and rats capitalized on a dense concentration of humanity, and soldiers constantly got infections. The ankle-deep exposure to muck didn’t help, and thoughts of a shower may as well have been fever dreams. Trench fever had a reprisal in World War II, as well, but the Sicilian cemetery precedes those conflicts by 15 centuries. “World War I was the perfect storm for a major outbreak of trench fever, but the bacteria was always very much prevalent,” says Tanasi, an archaeologist at the University of South Florida and a co-author of the paper.

Tanasi’s team was looking at 13 civilian and military sites from the last 5,000 years to study the prevalence of trench fever in different populations in France, Italy, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Russia, and see how the bacteria that causes the infection may have changed over time. The researchers didn’t notice much difference in prevalence among civilians versus military groups, despite its association with warfare. The fact that the bacteria showed up on the teeth of those 34 civilian Roman Christians buried in the catacombs suggests that their living conditions were squalid, Tanasi says. When a louse starts feeding on an infected host, the bacteria proliferates in the parasite’s intestine. Then, when the louse moves on to a new host, it poops the virus into its host through the skin. The bacteria easily moves through the bloodstream of the infected, which is how the Romans ended up with telltale bacteria in their teeth.

Trench fever wasn’t officially identified until after germ theory developed in the late 19th century, according to Carol Byerly, a historian of U.S. Army medicine who was unaffiliated with the recent paper. Besides the hallmark fever, symptoms include headaches, abdominal and shin pain, dizziness, and more.

“Trench fever had been around, it was in the environment, but it was just one in a whole suite of fevers and diseases that people couldn’t identify very well,” Byerly says. “No one wanted it, but people weren’t terrified of it.”

Among the near-800 American soldiers in World War I who were confirmed to have the fever, two died, according to a U.S. Army medical department report. Of greater concern to troops were the other illnesses plaguing the Great War’s battlefields, including typhus, dysentery, and the flu pandemic of 1918. Trench fever has hardly gone the way of the dodo: the last outbreak in the United States was in Denver this July. It’s one of several old-school bacterial infections that crop up now and again: Elsewhere in Colorado this July, a squirrel tested positive for bubonic plague.

Once the connection with unsanitary conditions and trench fever was clear, militaries made efforts to clean up their acts. The United States Army began routine delousings for their troops, Byerly says, which likely helped keep the American caseload at a fraction of that of their European counterparts, whose cases topped half a million.

The thread from the Sicilian catacombs to the wartorn fields of Europe is simple: Cleanliness is key. “You put two million men in trenches and don’t let them do the laundry,” Byerly says. “That’s how epidemics happen.”