This story originally appeared on The Public Domain Review, and is reproduced here under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license.

In the late 1860s, Jules Verne’s fictional Captain Nemo cruised the ocean deep, discovering new underwater worlds and creatures. In the same decade, the non-fictional Eugen von Ransonnet-Villez pursued his fascination with zoology by developing the technology to produce the first underwater pictures: seascapes drawn as he sat beneath the waves in his diving bell.

Ransonnet-Villez was born in 1838 into an aristocratic family in Vienna. Encouraged towards intellectual inquiry, he attended the Academy of Fine Arts at the precocious age of eleven, although he subsequently studied law. Employment from 1858 at the Imperial Ministry of Foreign Affairs allowed him to travel widely and pursue his interests in zoology and art.

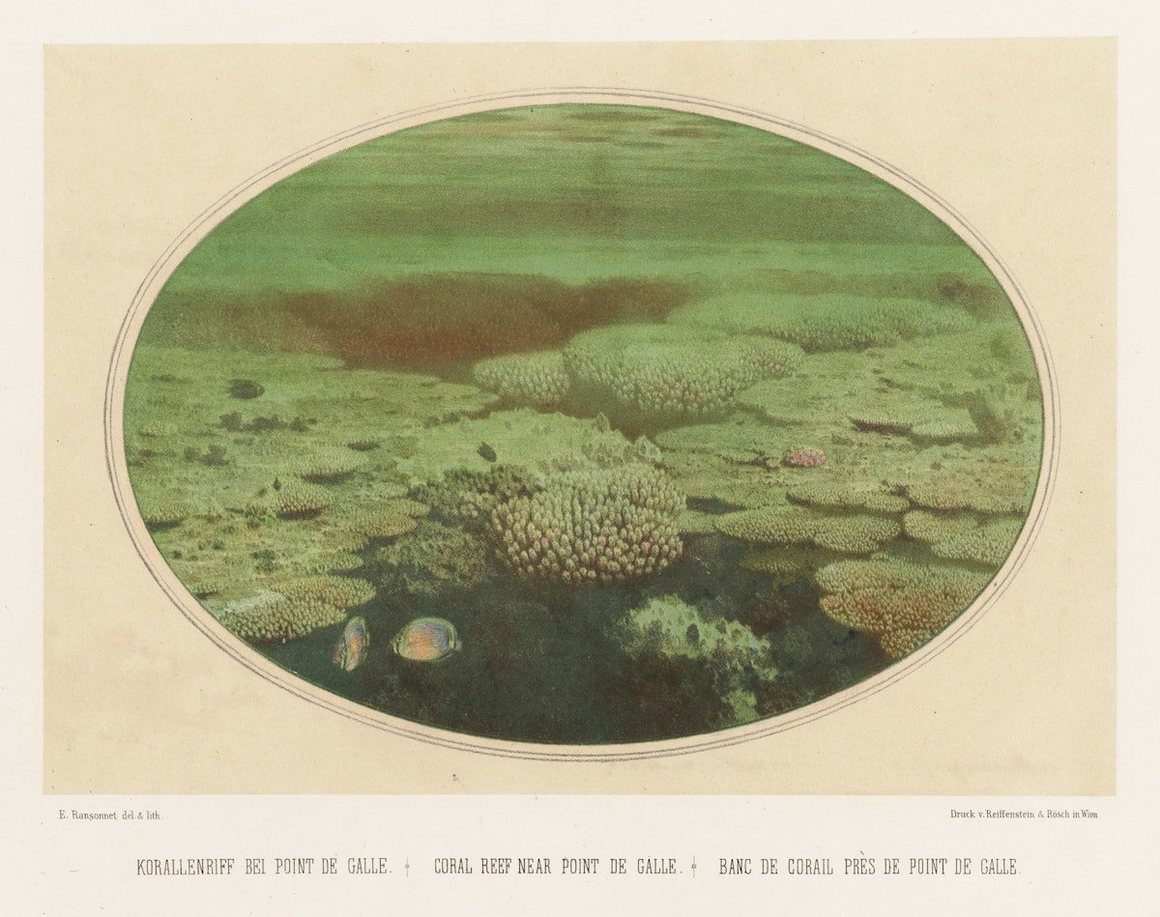

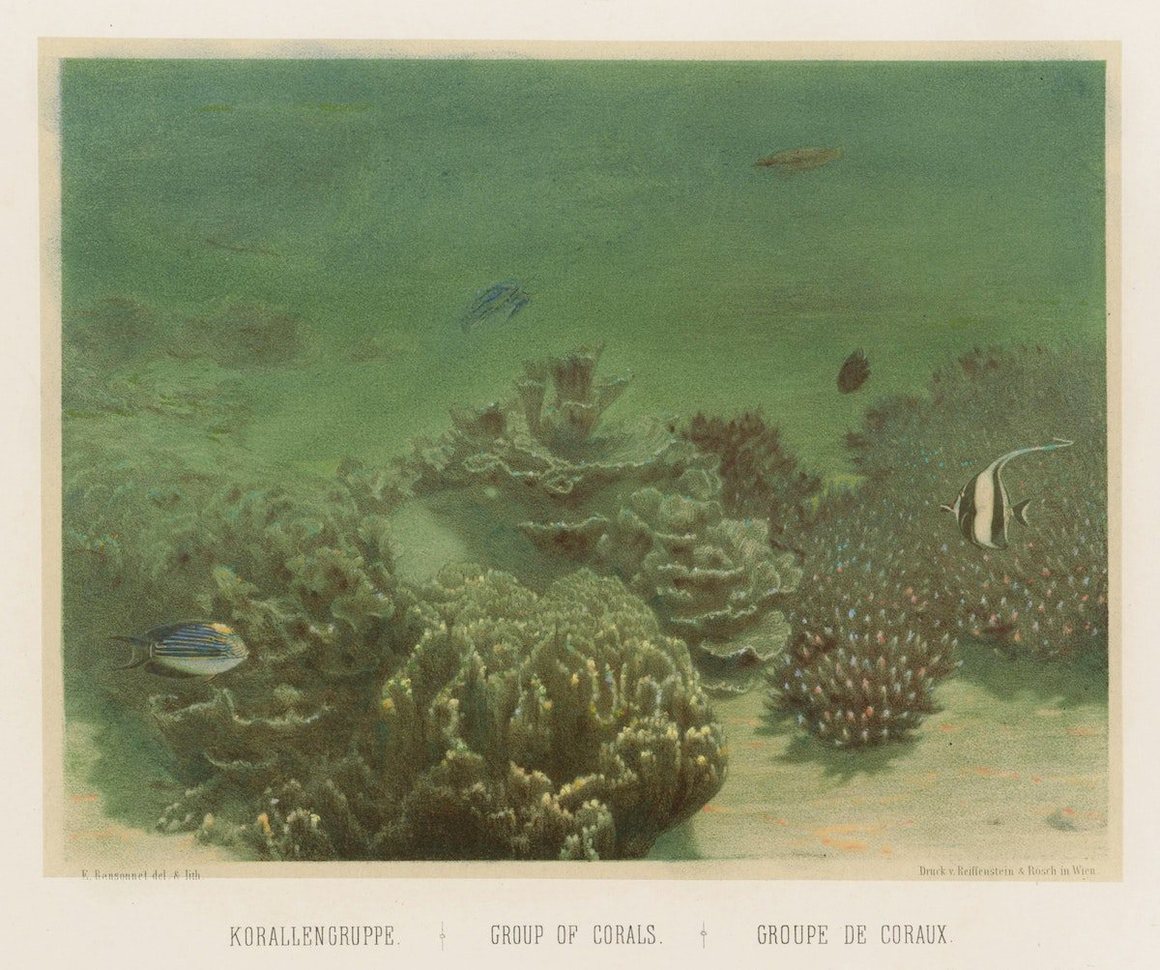

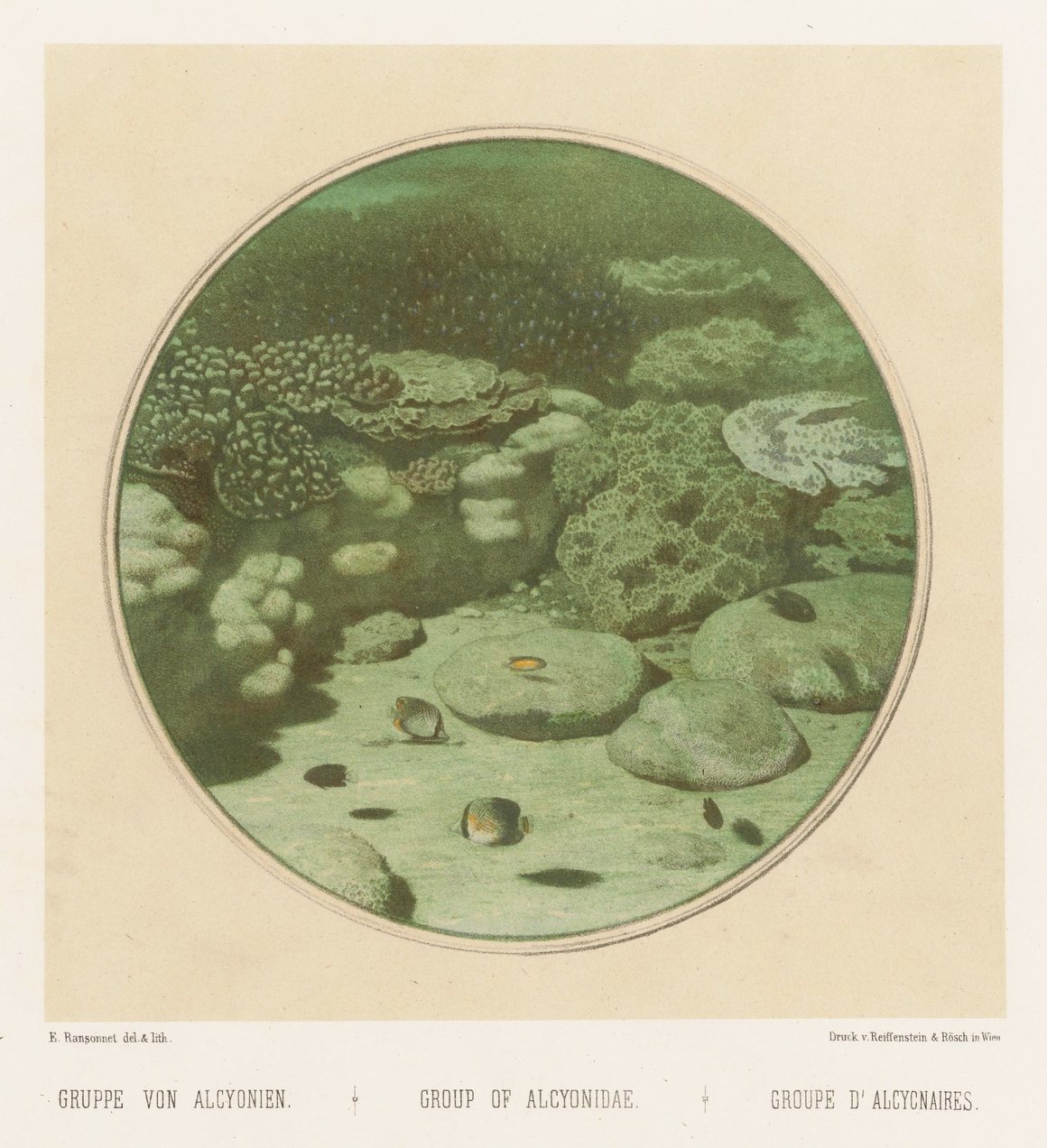

Following a visit to the Red Sea, Ransonnet-Villez brought out his first book, a volume of sumptuous and detailed lithographs of the seascape and the creatures. He based these on careful, boat-based observation. But during his next year’s visit to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Ransonnet-Villez took the plunge and designed for himself a submersible diving bell, in which he could descend beneath the surface to observe the environment more closely.

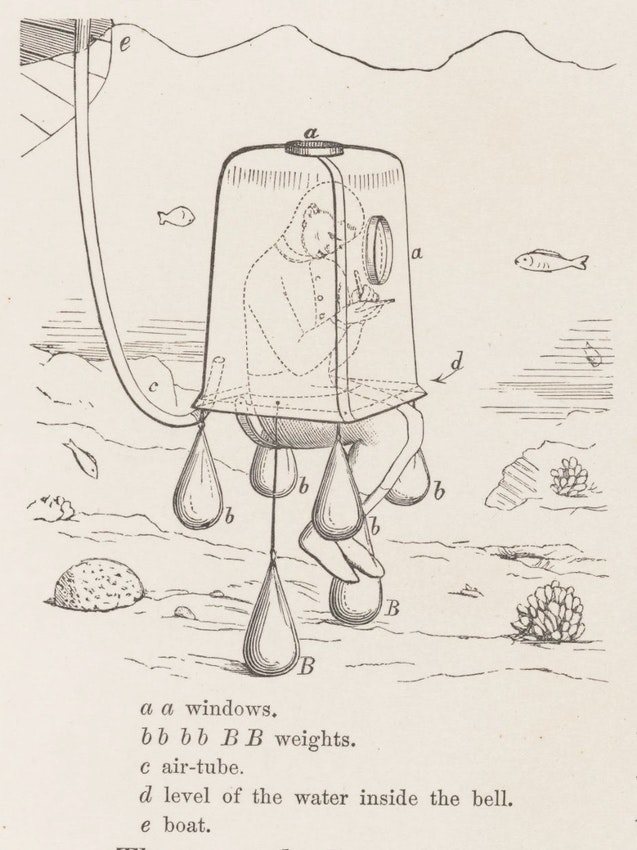

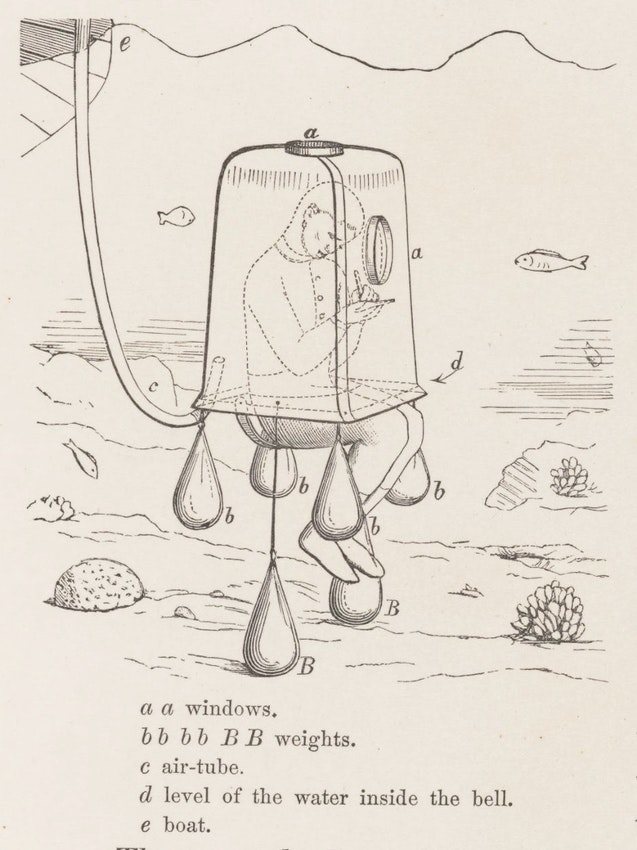

Measuring three feet high by two and half wide and deep, this submersible, of sheet iron and inch-thick glass, had the user’s legs sticking out of the bottom so that he could propel himself along the seabed at a depth of five meters or so. It was weighed down by cannonballs, and with air pumped in, the diving bell allowed him to descend for sessions of up to three hours. Jovanovic-Kruspel et al in 2017 point out that ”The sight of a dead dog floating on the surface nearby was a very welcome sight to Ransonnet as it proved to him that there were no sharks to be feared.”

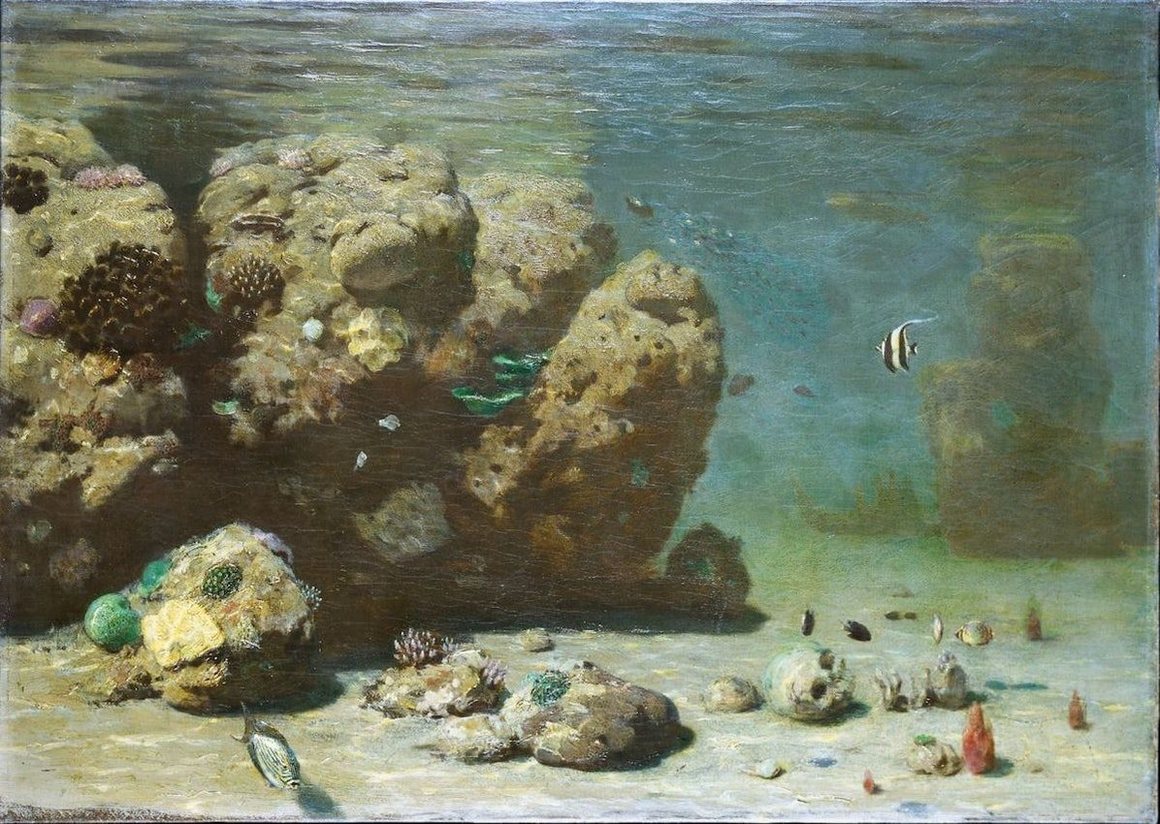

Undisturbed, and drawing with a soft pencil on greenish-colored, varnished paper, Ransonnet could use a tin box to send up to the surface his finished pictures, which he later painted over in oils: the first depictions of the seascape executed by an artist under the sea.

Four of these works are reproduced as lithographs (executed by Ransonnet-Villez himself) in his 1867 book Sketches of the Inhabitants, Animal Life and Vegetation in the Lowlands and High Mountains of Ceylon: As Well as of the Submarine Scenery near the Coast Taken from a Diving Bell, while the paintings themselves, and his correspondence, are mainly in the Natural History Museum Vienna, and in the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco.

Ransonnet-Villez moved on to experiments with color photography, and with an underwater telescope or reverse periscope, alongside collection and careful observation of samples, for later images of Singapore and the Adriatic.

But his underwater images are the most gripping. Jovanovic et al praise them as “a mixture between romantic-lyric underwater-landscapes and super realistic observations of the inhabiting organisms”—a characteristic nineteenth-century intermingling of the aesthetic with the scientific. She also points out his direct influence on Hans Hass, the titan of twentieth-century underwater photography.

We might place Ransonnet-Villez in the naturalist tradition, following Philip Henry Gosse, whose The Aquarium of 1854 was a high-water mark in interest in observing marine ecology at close hand. But Ransonnet-Villez deserves special mention for his dedication to conveying the sight and feel of the ocean, his literal immersion in his subject. As he explained of his diving-bell drawing excursions, “one’s normal sense of distance and size is completely lost. You soon realize that in the depths of the ocean you need not only learn how to move, but how to see and hear as well.”