The Archaeologists Recreating the Sounds of the Stone Age

This story was originally published on SAPIENS and appears here under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license.

On South Africa’s southern coast, above the mouth of the Matjes River, a natural rock shelter nestles under a cliff face. The cave is only about three meters deep, and humans have used it for more than 10,000 years.

The place has a unique soundscape: The ocean’s shushing voice winds up a narrow gap in the rocks, and the shelter’s walls throb with the exhalation of water 45 meters below. When an easterly wind blows, it transforms the cave into a pair of rasping lungs.

It is possible that some 8,000 years ago, in this acoustically resonant haven, people not only hid from passing coastal thunderstorms, but may have used this place to commune with their dead—using music. That’s a possibility hinted at in the work of archaeologist Joshua Kumbani, of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, and his colleagues.

Kumbani, with his adviser, archaeologist Sarah Wurz, believes they have identified an instrument that humans once used to make sound buried within a layer rich with human remains and bone, shell, and eggshell ornaments dating from between 9,600 and 5,400 years ago. This discovery is significant on many levels. “There could be a possibility that people used it for musical purposes or these artifacts were used during funerals when they buried their dead,” Kumbani hypothesizes.

The work offers the first scientific evidence of sound-producing artifacts in South Africa from the Stone Age, a period ending some 2,000 years ago with the introduction of metalworking. That “first” is somewhat surprising. Southern Africa has afforded archaeology a wealth of findings that speak to early human creativity. There is evidence, for example, that humans living 100,000 years ago in the region created little “paint factories” of ochre, bone, and grindstones that may have supplied artistic endeavors. Engraved objects found in the same site, dating back more than 70,000 years, hint at their creator’s symbolic thinking. Yet when it comes to music, the archaeological record has been mysteriously silent. “Music’s so common to all of us,” says Wurz, also at the University of the Witwatersrand. “It is fundamental.” It would be peculiar, then, if humans of bygone millennia had no music.

Instead, it’s possible that the musical instruments of South Africa have simply gone unnoticed. Part of the trouble is in identification. Determining whether something makes noise—and was deemed “musical” to its creators—is no small feat.

In addition, early archaeologists in this region used rudimentary techniques in numerous locations. Many archaeologists, Wurz argues, did their best with the approaches available at the time but simply did not consider the evidence for music in sites once inhabited by ancient humans. In short, they did not realize there could be a chorus of sound information trapped underground.

The oldest recognized musical instruments in the world are reminiscent of whistles or flutes. In Slovenia, for example, the “Neanderthal flute” may be at least 60,000 years old. Discovered in 1995 by Slovenian archaeologists, the item could have been created by Neanderthals, researchers believe. In Germany, scholars have unearthed bird bone flutes that a Homo sapiens’ hands could have crafted some 42,000 years ago.

Although some scientists have challenged the classification of these artifacts, many Westerners would readily recognize these objects as flute-like. They look very much like fragments from European woodwind instruments used today, complete with neatly punched finger holes.

In South Africa, archaeologists have discovered a number of bone tubes at Stone Age sites, but, as these objects lack finger holes, researchers have labeled the artifacts as beads or pendants. Kumbani thinks that these items could have produced sound—but identifying a possible instrument is difficult. Modern music scholars, after all, will point out that various cultures have widely different concepts of what sounds harmonic, melodious, or musical.

Music itself “is a modern, Western term,” argues Rupert Till, a professor of music at the University of Huddersfield in the United Kingdom. “There are some traditional communities and languages that really don’t have a separate concept of music. … It is mixed up with dance, meaning, ceremony.”

“This is a fantastic instrument,” Lund says of the buzz bone. “There are still people living in the Nordic countries, the oldest generation, who can tell you about when their grandparents told them how to make ‘buzz bones.’” Yet before Lund’s work, archaeologists had often assumed they were simply buttons.

Lund’s pioneering efforts set a template for others in the field. By creating meticulous replicas of historic objects, music archaeologists can experiment with creating sound from these items and then classify the likelihood that a given item was used to produce that noise.

New technological developments can also bolster a music archaeologist’s case as to whether an object produced sound: Repeated use leaves tell-tale signs on the objects, microscopic friction marks that hum their history.

In 2017, Kumbani and Wurz decided to embark on a project similar to Lund’s, using artifacts from Stone Age sites in the southern Cape. Like Lund more than 40 years earlier, they wondered whether there were sound tools in the region’s rich archaeological record that had been overlooked by other archaeologists.

To conduct this work, Wurz asserts, “you need a background in musical or sound-producing instruments.” She initially trained as a music teacher, and her past research has focused on human physical adaptations that gave rise to singing and dancing.

Kumbani, too, has a love for music, he says with a wide and somewhat sheepish grin. He previously investigated the cultural importance of an instrument called an mbira, or thumb piano, among communities in his home country of Zimbabwe for his master’s degree. In his slow, sonorous voice, Kumbani explains that, in fact, it was research for that project—as he sought out depictions of musicians in Wits University’s substantial rock art image archive—that eventually led him to Wurz.

Wurz and Kumbani decided to start their search by considering what is known about how peoples in Southern Africa have made sound tools, whether for music or communication more broadly. They turned to the work of the late Percival Kirby, an ethnomusicologist whose writings from the 1930s offered the archaeologists clues as to what traditional instruments might have looked like.

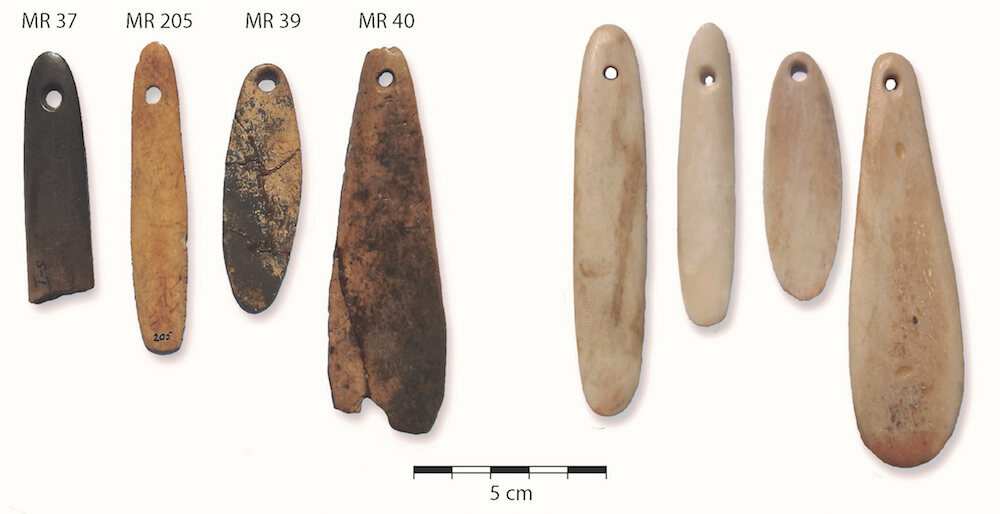

Then Kumbani set to work searching for mention of these sound tools in the archaeological record and looking for artifacts that physically resembled the ones Kirby detailed. Among the items he gathered were a suite of objects from the Matjes River site, including a spinning disk and four pendants.

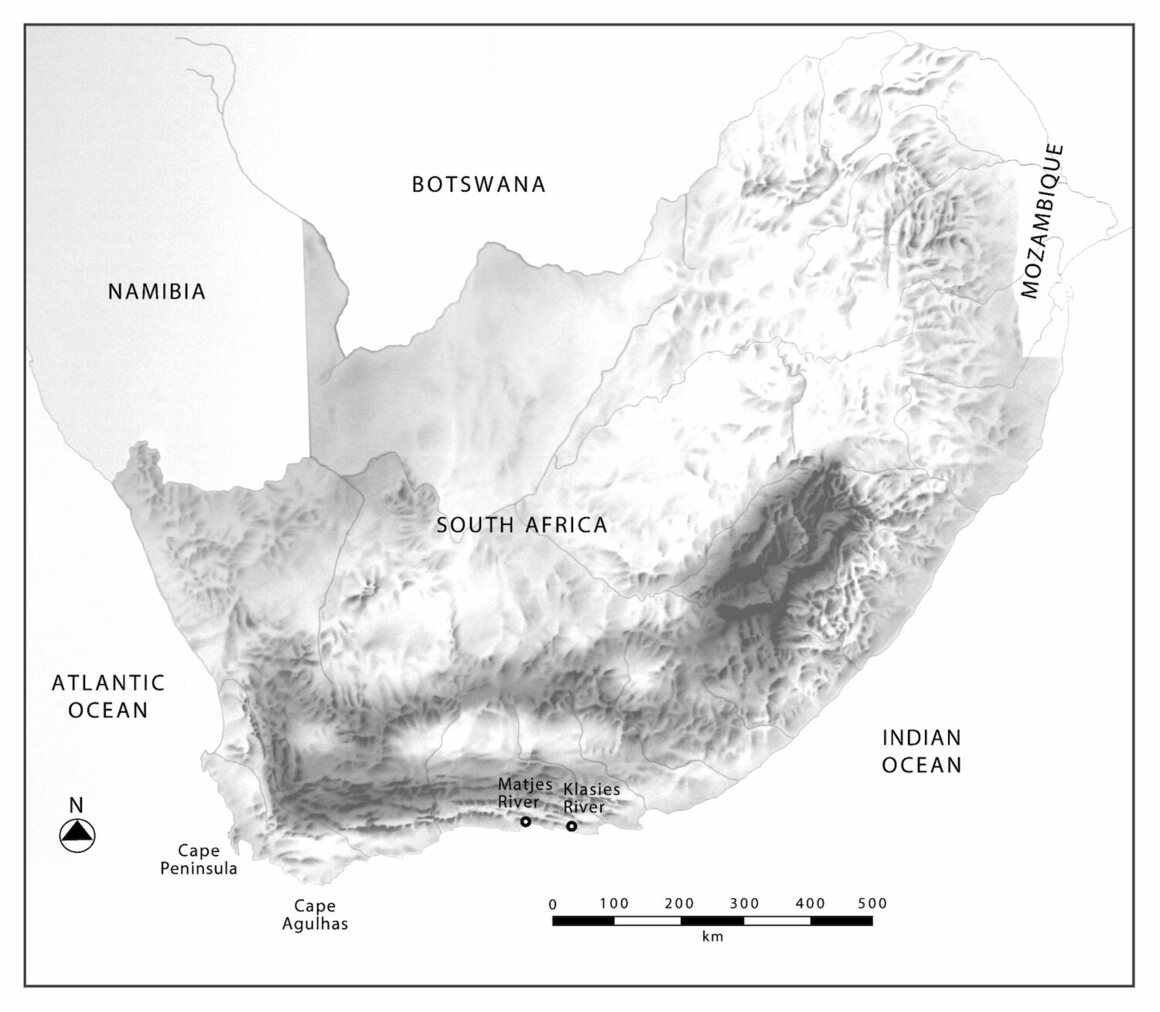

Kumbani found another spinning disk, the only other one mentioned in the literature, from another important archaeological site near South Africa’s Klasies River. This site, fewer than 100 kilometers away from the Matjes site as the crow flies, features a group of caves and shelters. Its treasured artifacts, first identified in the shelter’s walls in 1960, are interspersed with ancient human remains dating to about 110,000 years old and evidence of some early culinary innovation by H. sapiens. An earlier researcher had noted that the disk from the Klasies site, which happens to be about 4,800 years old, could, in fact, be a sound tool—but no one had investigated that possibility rigorously.

Once Kumbani had identified several promising candidates from both the Klasies and Matjes collections, his colleague Neil Rusch, a University of the Witwatersrand archaeologist, created meticulous replicas of each one out of bone. The next challenge: figuring out if a person had “played” these objects.

The only way to do so was to try themselves.

Every weekday evening in April 2018, after everyone else had gone home, Kumbani would stand in a teaching laboratory within the Witwatersrand campus’s Origins Centre, a museum dedicated to the study of humankind. By that time, the usually bustling building was silent.

Resting on a long wooden table, under the glow of bright fluorescent bulbs, were the two spinning disks from the Klasies and Matjes River sites. The narrow, pointed ovals fit in the palm of his hand: flat pieces of bone with two holes in the center. Kumbani threaded these “spinning disks” to test their sound-producing qualities.

Kumbani already knew the objects could make noise. He had previously tried to play them in his student accommodation in Johannesburg’s buzzing city center. The threaded spinning disks, he found, could rev like an engine. But not only did the throbbing sound disturb his fellow students, he quickly learned that the artifacts could be dangerous. A snapped string transformed the disks from sound tools into whizzing projectiles. He ultimately decided it was safer to perform his experiments far from possible casualties. (Watch him give it a try below.)

In the otherwise silent room of the university, Kumbani could experiment in earnest. Knowing the disks could make a sound was just his first question. He also needed to see how “playing” the disk would wear upon the bone material so he and Wurz could then check whether the original artifacts bore similar signs of use. Kumbani threaded each with different kinds of string, such as plant fiber or hide, to see how it might change the friction patterns.

Putting on gloves to protect his fingers from blisters, Kumbani played the spinning disks in 15-minute intervals and could only manage an hour a night. “You can’t spin for 30 minutes [straight]. It’s painful, your arms get tired,” he explains. “It was horrible, but I had to do it for the experiment.”

While the disks require a person to spin them, the pendants offered a reprieve. The four objects, all from the Matjes River, are small, elongated, oval- or pear-shaped pieces of bone with a single hole that might easily have been jewelry pendants.

In Cape Town, Rusch, who had made the replicas, created an apparatus to spin pendants for a total of up to 60 hours. His device looks like an old movie projector: a spoked wheel attached to a motor, with the pendant’s string tied to the edge. (Like Kumbani, he had learned that a broken string could turn the pendant into a wayward missile.) He created a tent out of black fabric in his home workshop to catch flying pieces of bone, and then he took them to a recording studio in Cape Town to document their sound.

All of the six artifacts from the Klasies and Matjes River sites made a noise, but the pendants were the real surprise. These items had been on display at a museum for decades before being stored in a box and forgotten about. Yet all four produce a low thrum when they are spun.

When Kumbani examined the originals and compared them to the well-played replicas, one pendant, in particular, had scuff marks that suggested it might indeed have been used to produce sound. When a pendant hangs from a person’s neck, the string rubs continuously at the top of the hole through which the string is threaded. But using a strung pendant to produce sound wears along the sides of the hole—as was the case for the one Matjes River pendant.

That one was “bigger and heavier,” Kumbani says. When played, it had a distinctive timbre: a rasping breath whose low frequencies sounded like inhales and exhales. But, he acknowledges, it could still have been jewelry—a sound-producing adornment.

In February 2019, Kumbani and his colleagues published their discoveries in the Journal of Archaeological Science. “The sound is not musical,” Kumbani says ruefully of the artifacts, “but it goes back to the question: ‘What is music?’—because people perceive music in different ways.”

Seeking sound tools among the Klasies and Matjes River site artifacts brings an entirely new perspective to these items, many of which have been poorly understood. At the Matjes River Rock Shelter, researchers have recovered more than 30,000 artifacts to date. But the excavation and categorization work—much of which was done in the 1950s—has drawn significant criticism from other scholars as being amateurish.

Physical anthropologist Ronald Singer, writing in 1961, described the excavation’s published summary as “a most despairing example of misguided enthusiasm, lack of experience in handling skeletal material, and inability to assess data.”

This carelessness, some have argued, had tragic consequences. The Matjes River Rock Shelter was a burial ground between 9,700 and 2,200 years ago. Yet today researchers do not know how many people were buried there, in part because the remains were poorly stored and labeled.

University of Cape Town biological anthropologist Rebecca Ackermann points out that many factors could have contributed to this failing. “It’s hard to say exactly what things they overlooked,” she notes, “[with] ancient cultural innovation, specifically in African contexts, racism would have played a role.” Ackermann adds that it’s hard to disentangle, however, whether these scholars were driven by race science or had simply absorbed values from a racist society.

By contrast, the quest to identify a long-lost community’s sound tools recognizes the complex culture, lifestyle, and humanity of the instruments’ creators. As Matthias Stöckli, an ethnomusicologist and a music archaeologist at the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, explains, “The sound or the sound processes and structures we’re interested in, they are produced by people who have a motive, they have a purpose, an attitude.”

“They give meaning to what they do, even if it is a signal or to terrify [in battle], if it is for dancing, for calming a baby,” Stöckli adds.

In South Africa, where there are remnants of many of humanity’s very first innovations, there could be hundreds of unrecognized sound-producing artifacts.

In October 2019, Kumbani presented some of his work to rock art specialists at Witwatersrand’s Origins Centre, the same building where he had spun the spinning disks for hours. He offered a new hypothesis: Clues to Southern Africa’s ancient soundscape could also be, literally, painted on the wall.

More specifically, he referred to Southern Africa’s extraordinary rock art. Painted in red-brown ochre, black manganese, and white from calcite, clay, or gypsum, the artworks are thought by archaeologists to have been created over millennia by hunter-gatherer communities. The descendants of these groups include the San people, who still live in the region today.

There is no firm age for the majority of these paintings, but one 2017 study managed to date a painting for the first time, suggesting its pigments were about 5,700 years old. That age would make the artists contemporaries of the people burying their dead in the Matjes River’s susurrating rock shelter.

Many of these paintings depict an important spiritual rite of the San people: the trance dance. They depict half-animal, half-human shapes and dancing people, offering glimpses into a ritual at the boundary between the spirit world and the physical world.

One particular example, hundreds of kilometers northeast of the Matjes and Klasies River sites, in the foothills of the Drakensberg Mountains, features an ochre-brown figure that, to Kumbani’s eyes, appears to be playing an instrument. The object—which Kumbani calls a “musical bow”—includes a bowl at the bottom and a long stem, not unlike a banjo, and the figure is hunched over, drawing a white stick, like a cello bow, over the stem. Other painted figures sit and watch while some stand and raise their feet, caught in a frozen dance.

Though some of Kumbani’s colleagues are skeptical of his interpretation—he recalls one saying “you see music everywhere”—others acknowledge the idea is worth exploring. David Pearce, an associate professor of archaeology at the Rock Art Research Institute at Witwatersrand, notes that studies of the San people suggest “trance dances [are] accompanied by singing and clapping, and that dancers [wear] rattles on their lower legs.” He adds that “the songs are said to have activated supernatural energy in the dancers, helping them to enter the spirit world.”

Though to date, Kumbani and Wurz have not found the remnants of musical bows in South Africa’s Stone Age archaeological record, their search continues. Now that these archaeologists have begun to hear the sounds of distant human societies, it’s impossible to dismiss them, like an ancient earworm echoing across time. The first step is to find the now-silent sources of sound that could be sitting forgotten in a box in a museum.