Unearthing Skeletons: John Carpenter on Lost Themes III and Scoring Halloween

An unrivaled master of the macabre, John Carpenter is best known as the man behind horror classics like “Halloween,” “The Thing,” and “Assault of Precinct 13.” Rightly hailed as masterpieces on the strengths of their sharply unnerving stories and muscular direction, Carpenter’s best films—also including “Escape from New York” and “They Live!”—benefit from his pioneering work as a composer of electronic music.

The adventurous synthscapes of these films heighten their atmospheres of dread and suspense by practically unquantifiable levels; try to imagine “Halloween” without its propulsive synths or “The Fog” without its hammering percussion. It’s been a decade since Carpenter last directed a film—supernatural horror “The Ward”—but his recent career focus on music has made it undeniable that the legendary filmmaker also deserves recognition as one of horror’s greatest composers.

With record company Death Waltz, Carpenter has reissued many of his classic soundtracks across the past few years; he also recorded the ominous score for David Gordon Green’s 2018 “Halloween” reboot and returned in the same capacity on its upcoming sequels. But the most striking reminder of Carpenter’s versatility as a musician can likely be found in his on-going series of Lost Themes albums, which offer original scores for films that don’t actually exist.

As Carpenter describes it, speaking by phone from his California residence, “They’re soundtracks for the movies in your mind.”

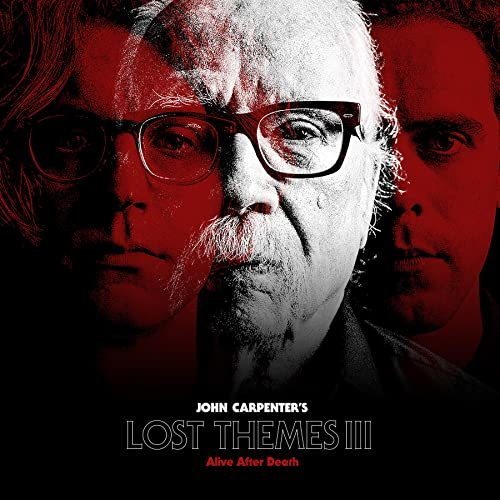

Released last week, Lost Themes III: Alive After Death was recorded, like the last two, with the filmmaker’s son Cody Carpenter and godson Daniel Davies. The trio’s familial comfort and time-tested rapport as collaborators shows on the new record. Carpenter’s first original non-soundtrack music in five years, its ten eerie tracks represent an evolution for him as a musician in its sonic sophistication and emotional impact.

“Weeping Ghost,” an early single, is filled with throbbing arpeggios and blaring synthesizers; its relentless three-note groove has a harder-edged crunch than many of Carpenter’s most enduring film scores, though there’s a sly, labyrinthine feeling to the track that suggests the cosmic corkscrews of “In the Mouth of Madness.” “The Dead Walk,” meanwhile, leans on snatches of Gothic church organs à la “The Fog,” only fully roaring to life halfway through with one of Davies’ mighty guitar riffs. And “Carpathian Darkness” might be the most interesting closer of any Lost Themes record, conjuring a real sense of otherworldly menace with twinkles of minimal but fiendishly well-placed piano.

To hear it from Carpenter, the process of making Lost Themes records is fluid and collaborative. Whereas the economy of Carpenter’s most famous compositions often arose out of necessity—famously, he composed his “Halloween” score in just three days to save the film after execs yawned through an early cut without music—Lost Themes records have never come together under pressure.

“My whole career, I’ve been doing things on schedules,” he says. “For this, forget it. This is not that way. It depends on your personality: if you’re the kind of person who’s looking for some kind of perfection, it’s impossible [to make this kind of music]. I’m very far from that kind of a person.”

Especially in quarantine, Carpenter says he’s not been overly consumed with making music. Instead, he’s dedicated ample time to his two preferred leisure activities: playing action role-playing games, and watching basketball games on TV. Last year’s “Assassin’s Creed Valhalla,” Carpenter says, has been occupying the bulk of his time, though 2018’s “Fallout 76” is another perennial favorite; while he’s not attached to direct any projects at this time, Carpenter says he’s particularly open to directing a video-game adaptation.

Does video-game music influence his artistic process as a musician? “Hell, no,” says Carpenter, emphatically. “I love some video-game scores, but you’d have to go back to ‘Megaman’ or ‘Sonic’ to find the ones I love.” Instead, he explains, “the music I make arises out of several sources: classical rock, old film music, rock ‘n’ roll, all kinds of music I’ve experienced in my life. That inspires me.”

Asked if he can discuss any of the Lost Themes tracks in detail, Carpenter demurs. Talking to the veteran filmmaker about this release, it quickly becomes clear how much of his creative process he prefers to keep private—and that a not-insignificant part of it seems to remain on a subconscious level, even for him.

“It comes out of instinct,” Carpenter offers. “It isn’t planned. We search for the right sounds and just sort of start with something, whether it’s a melody, a pad, or a baseline. From there, it all just comes out. Music is easy for me, because it’s all instinctual and improvised. I have no idea where it comes from.”

And for the most part, he’s not too interested in finding out. Given the scale of his contributions to synthesizer music, Carpenter’s more concerned these days with “not redoing something I’ve done before, some old classic,” he says.

“For the most part, a song usually starts with Cody and I, sometimes from scratch, with a bassline or arpeggiator,” adds the director. “And then we start building. Listening to the sounds out there available today on computers, it’s unbelievable and almost infinite.”

Next, father and son enlist Davies, whose rock bona fides are at once genetic (he’s the son of The Kinks guitarist Dave Davies) and proven (in bands like Year Long Disaster, Karma to Burn, and CKY). “Everybody has their own strengths, and Daniel is a master guitar player, in rock ‘n’ roll bands, so he comes by this stuff naturally,” says Carpenter. “Cody’s an amazing player, too; he can play like nobody’s business, and technically he’s really good. I’m pretty experienced—and I bring the bad jokes.”

Asked whether any of those bad jokes bear retelling, Carpenter’s glee shines through for a moment.

“Originally, when we started, the ‘Skeleton’ work-in-progress track was called ‘Skeleton’s Penis,’” he says, chuckling. “I don’t know why. Because it’s ridiculous. My boys convinced me that wasn’t a good idea to really do, so ‘Skeleton’s Penis’ became ‘Skeleton.’”

Does this mean there’s an uncut version somewhere on his hard drive, awaiting release? “I think it should have been ‘Skeleton’s Penis.’ We could have broken some ground. An uncircumcised version, yes! What do you think about that, eh?”

Unlike his Lost Themes records, which thrive in their sense of freedom, Carpenter’s soundtrack for 2018’s “Halloween” was studiously reminiscent of his score for the original “Halloween,” fashioning “remade” tracks that maintained its air of plinking, piano-driven menace while incorporating modernized sounds to cast everything in a fresh light. The title track was accordingly scaled up with a more powerful, industrial bass; if the original could make your speakers throb like none other, the remake aimed to blow them out. And while Laurie’s theme in the original “Halloween” was brooding and melancholic, the dirge of a doomed victim, her accompaniment in the new film cut deeper and more forcefully, speaking somehow to her evolution from terrorized babysitter to hardened survivor.

“Doing the music for the new ‘Halloween,’ we have to start when the movie’s done, and then we go through it scene-by-scene,” explains Carpenter. “And that’s great fun. We provide all sorts of things to support the image, the characters, and the vibe. It’s most fun because I don’t have to direct it.”

Carpenter won’t divulge any secrets about his score for “Halloween Kills,” though he’s as excited as anyone to watch it, hopefully, on the big screen. “Wait ‘til you see ‘Halloween Kills,’” he teases. “Wow. First of all, the film’s spectacular. This is the ultimate slasher film. It’s rough, fun, and we had a great time making the music. It’s just fantastic.”

Ready-made as the “Halloween” films are to watch with a crowd, Carpenter’s just as eager to get back on the road to perform Lost Themes tracks at concert halls around the country. But with the world still in the grip of COVID-19 lockdown measures, “I’m worried,” Carpenter admits.

“The whole secret [to survival] is just to isolate,” he affirms. “That’s what I’ve done all year. But I’m up in the Hollywood Hills. It’s a beautiful city, with beautiful weather, and I have everything I need. I mean, what the hell? It’s not hard.” But as the pandemic’s toll has continued to ravage artistic institutions of all shapes and sizes, it’s difficult to stay optimistic.

“Theaters are closing,” adds the director. “I don’t know what’s going to happen to my business; COVID killed it! People used to run out on date nights, go out in groups to see these movies. I guess they might again when it’s safe. We’ll see.”

Carpenter’s modulated synth textures still exert a formidable influence over genre filmmaking. So iconic are the director’s spartan compositions that dozens of horror scores have been made in their image; they’re often described simply as “Carpenter-esque.”

Look everywhere from Netflix’s nostalgia-poisoned “Stranger Things” (the third season of which squeezed particular narrative juice out of “The Thing”), to stylish horror-thrillers like “It Follows” and “The Guest,” which revel openly in their ‘70s and ‘80s genre aesthetics. IFC Midnight’s incoming “Come True,” from Anthony Scott Burns, extends its “Prince of Darkness” homage to the oppressive, stop-start synth score.

One particularly Carpenter-inspired film from last year was Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles’ “Bacurau,” a Weird Western from Brazil that’s earned critical acclaim and several end-of-year best-of prizes en route to potential Oscar nods next month. Twisting together elements of ‘70s sci-fi, spaghetti Western, war drama, grindhouse, and blistering political satire, the film follows residents of a small town in the Brazilian sertão who take up arms against ominous outside forces that threaten to wipe them literally off the map.

Described in Polygon’s review as “the best John Carpenter movie Carpenter didn’t actually make,” “Bacurau” is forthright about its debt to the horror maestro, even of its compact and stylish exploitation of a single setting for genre kicks. A fictional school in its central village carries the name of one João Carpinteiro, while the film’s widescreen CinemaScope photography and heady mixture of split diopters, slow dissolves, and wipes recall ‘70s and ‘80s thrillers like “Assault on Precinct 13.” But the film’s most fascinating callback to the filmmaker is the direct use of Carpenter’s gunslinger-esque “Night,” off his first Lost Themes record, in a key sequence.

“Say this again, ‘Bacurau?’” says Carpenter, when asked about the film. “I’ve never heard of it. Don’t know it. I don’t remember this, but they probably got the rights to use the music. So, god bless ‘em! They had to pay!” He agrees to add the film to his watchlist.

Still, Filho and Dornelles’ use of “Night” in “Bacurau” speaks to Carpenter’s guiding vision for the Lost Themes records. Here’s an instance of two emerging filmmakers, inspired by his body of work, using one of Carpenter’s compositions to fully realize their own darkly thrilling vision. There’s a neat, cyclical symmetry to this that the director can appreciate, even as he prefers to keep his own ideas for visualizing Lost Themes tracks close to the vest.

“That’s what this music is all about, and that’s what’s fun about it,” says Carpenter. “My job is done when the music is done. I just want to provide something visual through sonics; you provide the visuals and the story, and I’ll provide the music. In a second, I’ll make a movie, if it’s good and I don’t have to kill myself making it. But I have another career here.”

Get a copy of Lost Themes III here.