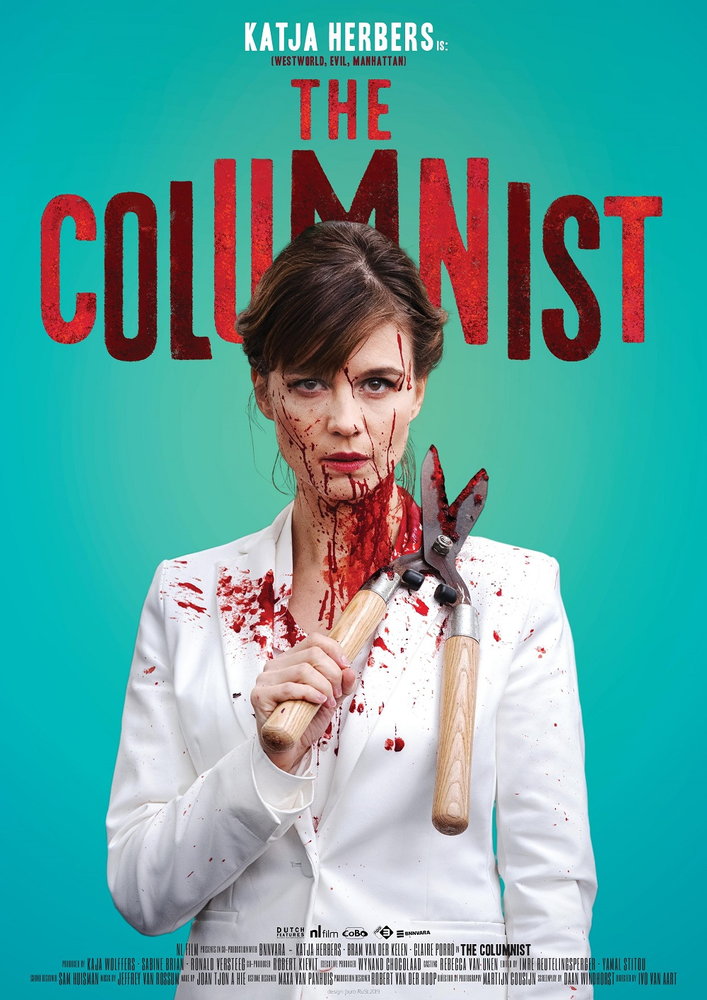

To Help a Rare Brazilian Parrot, Start With a Crossbow and Rappelling Beekeepers

Maximo Cardoso had never used a crossbow before, but he was intuitively able to assemble the Barnett Raptor FX, a model typically marketed for deer hunting. The field guide also displayed natural marksmanship. So it was agreed: He would be the one to launch the poison.

At the base of a sheer rock face amid dry scrub in Bahia, Brazil, decked out in a beekeeping suit, Cardoso took aim at a 45-degree angle, the crossbow loaded with bolts modified to carry glass vials of insecticide. He was targeting small cavities in the red sandstone above that held nests of invasive Africanized honeybees. Depending on the size of the hive and difficulty of shot, it took anywhere from a single bolt to as many as nine for each of 52 hives. Two or three hits usually weakened a hive enough to allow the team’s work to continue.

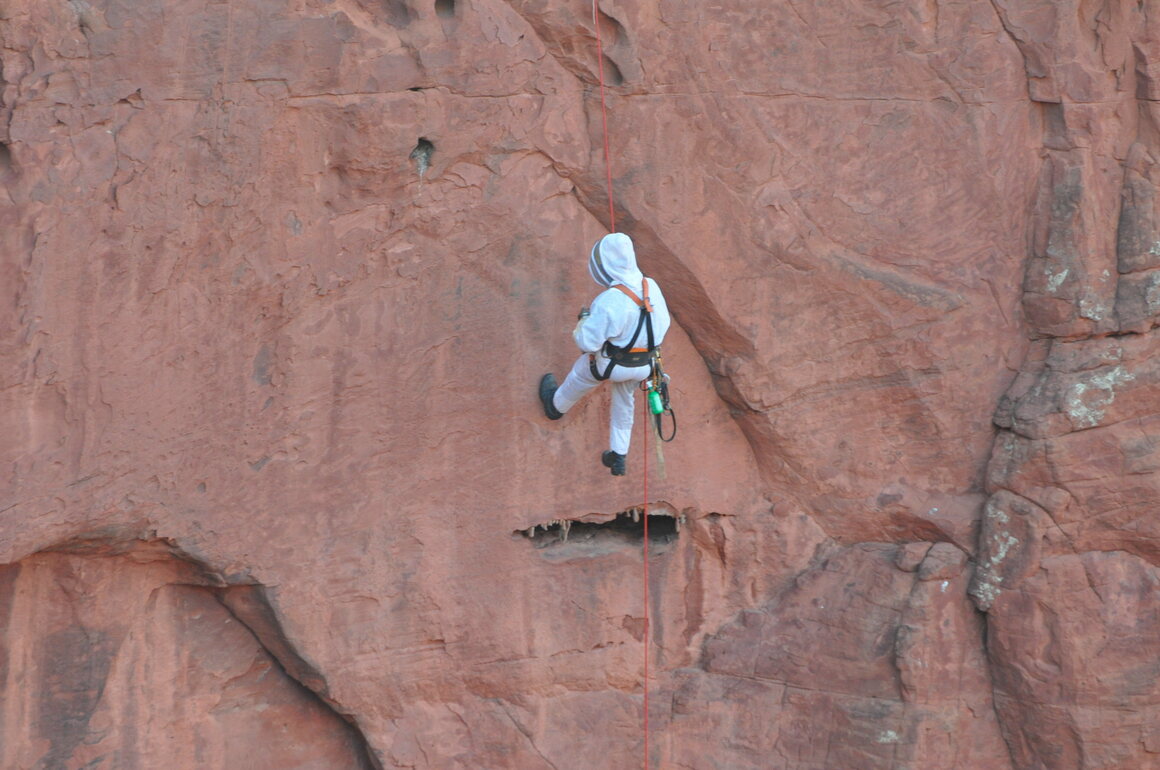

Over the following days, the team, with members from five countries, checked the activity of the hives with binoculars and walked the base of the cliff looking for dead bees. If the coast was clear, a pair of expert climbers, also wearing protective bee equipment, rappelled to the cavities from above to inspect them. One used a smoker to pacify the remaining bees while the other further treated the hives with insecticide if necessary. Eventually they were able to chip out the honeycomb by hand, all while dangling several stories in the air.

The bees weren’t the real subject of this scientific conservation effort. The cliffs in the hot, dry caatinga of Bahia are historic nesting grounds for one of the rarest parrots in the world, Lear’s macaw. There, bees and parrots compete for homes in the same small openings in the rock, and researchers suspected that clearing out hives would provide more nesting and breeding opportunities for the macaws, which are bright blue, with yellow cheeks, and named for British poet Edward Lear.

Most of the crossbow-related fieldwork was conducted in 2016, but the results of long-term observation were published in 2020 in the journal Pest Management Science. The team found eight new Lear’s macaw nests in 52 cavities that received their novel crossbow treatment. Over that time, there were no new parrot nests at a similar number of untreated sites.

“Where there are parrots and there are large bee populations, there will be competition,” says Donald Brightsmith, a parrot researcher at Texas A&M University who was not part of the study. The reclaimed nesting sites suggest that the presence of bees can limit the Lear’s macaw population.

Biologist Erica Pacífico had suspected that might be the case since 2009, when locals told her there were Africanized honeybees in former Lear’s Macaw nests. These hybrid “killer bees” had escaped a quarantine facility in the 1950s, and have since spread around the Americas. They’re known to be particularly defensive, and can chase people who disturb them. Pacífico knew that removing hives of them would require precautions. “Africanized bee stings are dangerous in any circumstance,” she says, “but during rappelling a cliff about 80 meters, in remote areas, the chance of rescue is very low.” In addition to local expertise, Pacífico recruited bee experts and experienced climbers from the organization Explore Trees for the most dangerous parts of the effort. Team members had worked on bee and parrot projects before, although never in cliff nests.

Entomologist Caroline Efstathion, founder of the Avian Preservation and Education Conservancy, recalls an 11-hour bus ride to a research station, with drives of six-plus hours between the study’s four main sites. The team had to pack almost all supplies in, including water, tents, and all their climbing gear.

Local attitudes toward Africanized honeybees are mixed, the team says. Many people consider them a nuisance, but others value the honey—after all, it’s why they were bred from European and African varieties—and the glue-like propolis, a traditional medicine. Honey gatherers build ladders of branches wedged into the cliffside. “As far as they’re concerned, these are their bees,” says Efstathion. To complicate matters, honey collection can be used as cover for parrot poaching.

Pacífico was eventually able to get community support and financial backing from a group of conservation organizations to determine if removing bees would benefit the macaws. The experimental hive removal could commence, but the trouble was how.

The first step would be to get insecticide up into the beehives. A paintball rifle might’ve reached the highest nests, says Efstathion, but they were unable to import one. Study coauthor Jamie Gilardi, executive director of the World Parrot Trust, suggested the crossbow, which conservationists use to sling ropes over high branches when studying other parrot species that nest in trees.

After some tinkering, the bolts were tipped with three-milliliter glass vials filled with a smidge of powdered permethrin, an insecticide and repellent sold as a lice treatment. The goal wasn’t to kill all of the bees, says Efstathion. Instead, trap boxes treated with bee pheromones were placed near the cliffs to give colonies a place to relocate. Efstathion had used a similar “push-pull” method with permethrin around the world to treat the nests of parrots, starlings, and barn owls, and had studied its effects on bird health.

“By the time we got to Brazil, I was one-hundred percent certain [permethrin] would not harm Lear’s macaw,” says Efstathion. However, before any larger-scale effort can get underway, the team needs to monitor effects of the treatment on other species they observed in the cliffs, including “ants, beetles, native bees, tarantulas, geckos, rats, bats, and their ectoparasites.” But the results in Bahia so far show a lot of promise for continuing to support the endangered birds.

At their low point in the 1980s, there were estimated to be just 70 Lear’s macaws left in the wild. Those numbers have rebounded thanks to conservation efforts from both the Brazilian government and private organizations, Pacífico says. While the top threats to parrots are habitat loss and illegal trade, “Bees are on our radar as parrot biologists,” says Brightsmith, but it wasn’t clear until now that they parrots would make use of extra nesting space if bees are removed. The recent study suggests that they will. “The problem is we can all know a problem in the back of our heads,” he adds, “but doing the science and getting it published is not trivial.”