Why an English Manor Is Deploying Parasitic Wasps and Moth Pheromones

Battle wasps, to war! At least that’s the way it sounded when conservators in England recently announced that they were going to deploy an army of wasps to fight a moth infestation at a stately manor home. But alas, the reality is less an epic battle and more like a quirky rom-com (with a little parasitism thrown in).

Blickling Hall, reportedly the birthplace of Anne Boleyn and a celebrated example of both Jacobean and Georgian architecture, is under attack. Mild weather in eastern England and other factors have resulted in a population boom in common clothes moths (Tineola bisselliella), which can munch their way through tapestries, textiles, and other treasures.

So to tackle the infestation, the National Trust, which manages the property, is trying an innovative, multi-tiered approach, including wasps that parasitize moth eggs. When word got out that Blickling would introduce an army of parasitic wasps, some media outlets took the militaristic imagery and ran with it.

“I think one outlet called the wasps ‘our winged crusaders,’” says Hilary Jarvis with a chuckle. Jarvis, assistant national conservator at the National Trust, organized the trial, which will begin once warmer temperatures arrive. She’s amused by some of the battle-ready language and the attention it has brought. She even indulged in it a bit herself: “When I first started writing a paper on this, I said ‘All guns blazing!’ I removed that. It’s not very National Trust.”

The much-ballyhooed wasps are only one part of the trial. The team will also put out chalky tabs of electrostatically charged female moth pheromones. Attracted by the scent, the male moth draws near and gets coated with the stuff.

“The scientific term is, I believe, ‘auto-confusion,’” says Jarvis, with obvious glee. “Imagine you’re walking through the perfume aisle looking for the Chanel, but people keep spraying you with all sorts of things. By the end of the aisle you can’t smell anything. He’s bewildered, and because he smells like a female, other male moths are attracted to him.”

And while mass confusion reigns among the male moths, the eggs laid by females go unfertilized. “We’re disrupting the lifecycle,” Jarvis adds. “We’re not harming them, we’re just saying, ‘Please, no more babies.’”

As for the wasps, they’re a far cry from the black-and-yellow winged assassins of summer picnics. Also known as the dwarf wasp, pinhead-sized Trichogramma evanescens poses no threat to humans—or anything, really, other than moth eggs. T. evanescens doesn’t even fly well.

“My biggest worry is, are they going to find the eggs? They don’t really fly,” Jarvis says. “They’ll be essentially running across football pitches.”

But determination can go a long way, says Mylène St-Onge, scientific director at Canadian firm Anatis Bioprotection. St-Onge is not involved in the Blickling Hall trial, but has studied Trichogramma wasps for more than a decade, including their early use for pest control in cornfields and flour mills. Her team now rears them by the millions each year for customers.

“They walk. Fast,” says St-Onge. The insects have one goal during their two-week lifespan. “All they do is search for moth eggs. They walk around saying, ‘I just want to reproduce!’”

So tenacious are these little wasps, St-Onge adds, that they can locate moth eggs outside areas targeted by traditional, chemical-based extermination efforts. Trichogramma lay their eggs in the eggs of several moth species, which provide a ready food source for their own offspring during the larval phase. Once the wasps reach adulthood, they go off to look for more moth eggs, and the cycle begins again.

“The [adult wasps] don’t eat anything. They don’t excrete anything. They form dust when they die. That’s the only part that bothers me,” says Jarvis. “Dust is our number one villain. We’re paranoid about dust.”

At Blickling Hall and other National Trust properties, house teams follow a rigorous daily cleaning protocol based on research that has determined where dust particles are most likely to fall. (Aside from being unsightly, dust can be full of organic material, environmental pollutants and other substances that can damage items or attract pests.) The arrival of the dwarf wasp battalions may shake up that careful routine. “If the tapestries start to look a bit grayer, we will stop. It’s just a trial,” Jarvis says, unexpectedly invoking the words of a hawkish former defense secretary. “Like Mr. Rumsfeld said, there are known unknowns and unknown unknowns and all that.”

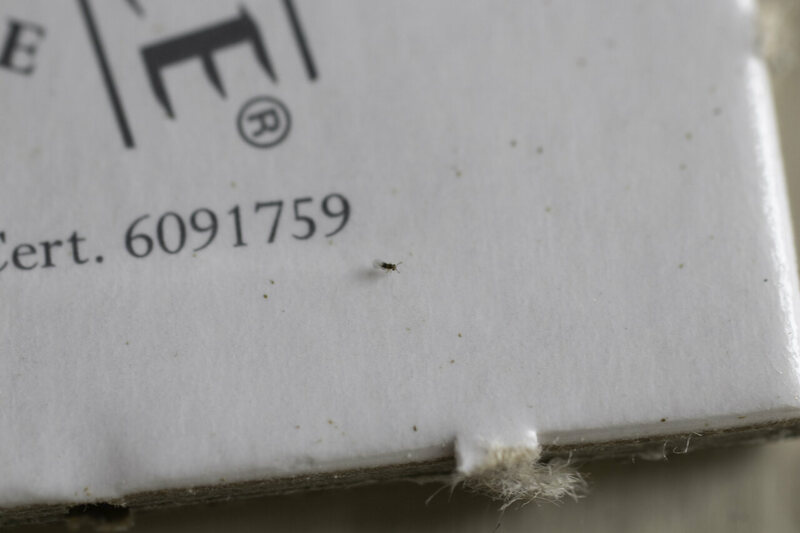

Once England’s spring temperatures reach 60 degrees Fahrenheit and moth season starts, the Blickling Hall team will place pheromone tabs and dwarf wasp containers in at least 11 rooms throughout the sprawling mansion. The cardboard containers are not much bigger than a credit card but contain thousands of wasps ready to hunt for moth eggs. The deployment process is notably unnoteworthy, says Jarvis: “Someone puts a bit of card out and everyone looks at it and nothing happens.”

Stately homes and other institutions charged with protecting valuable and often fragile items are turning to biological control options more than ever, says consultant Stephan Biebl. Based in Germany, Biebl works with collections around the world to create integrated pest management programs that will be gentle on irreplaceable heritage but tough on the organisms attacking them. He credits an increase in environmental awareness worldwide for a growing interest in the approach.

“In the past there were many applications with chemical products, which the conservators nowadays want to avoid,” Biebl wrote in an email. “The demand for beneficial insects is also increasing more and more.”

Biebl’s website includes a chart of some of the useful, tiny bioweapons in his arsenal, such as the warehouse pirate bug (Xylocoris flavipes) and bacon beetle ant wasp (Laelius pedatus), in the high-stakes battle against destructive moths, beetles, and other critters.

While more museums are catching on, the idea of pitting nature against itself to prevent pests from destroying valuable heritage is not new. At night in Portugal’s Mafra Palace library, for example, colonies of bats have hunted book-munching pests for centuries. What is innovative about the Blickling Hall program, however, is the combination of multiple methods originally developed for agriculture and other fields. It’s just not particularly dramatic.

“I do worry some of the visitors will come expecting to see amazing things happening,” Jarvis confesses. “They won’t.”