SLAMDANCE 2021: Interview With Jurgis Matuelevičius, Writer-Director Of ISAAC

One of the first sounds you hear in Jurgis Matuelevičius‘ Isaac is the Wilhelm scream. Over the years, the effect – one of the most overused and saturated in the business – has worn out any dramatic stature it may have once had. It’s a misleading introduction to Isaac. A disorienting one. For what follows is a burly, uninterrupted eight-minute sequence colliding the chaos of Lithuanian nationalists and the moral downfall of one man, Andrius (Aleksas Kazanavicius).

Told in three parts twenty years after the opening events, Isaac observes Andrius as his guilt continues to clot in Soviet Lithuania. His mental insurrection is paired with the story of his old friend, Gediminas Gutauskas (Dainius Gavenonis), who left Lithuania in the midst of its Nazi occupation and has returned home to direct a feature film about the pogrom Andrius witnessed. Big brother KGB looms over the project, however, convinced, based on the script’s accuracy and detail, that Gutauskas was involved in the massacre.

Film Inquiry recently spoke with Matuelevičius about his incredible and impressive debut, touching on his diversions from the Antanas Skema short story, Lithuania’s complicated relationship with its own history, and the backlash he expects from his hometown audiences.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Luke Parker for Film Inquiry: I want to start this conversation by talking about how you started this film: a very confident and involved one-shot sequence that climaxes with the Lietukis garage massacre. Can you describe how you choreographed that scene? Because there were clearly a lot of moving pieces, including historical accuracy for you to consider.

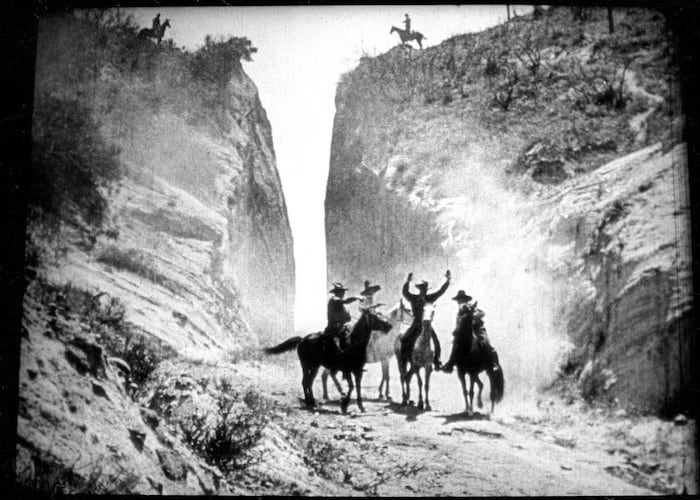

Jurgis Matuelevičius: I started directing this scene by looking at some real photos from the massacre, which took place in 1941. There were about 18 pictures that I found in KGB archives. So, I wanted to find a really similar place because the exact location in our country has been turned into a school.

In the pictures, I saw that there were lots of people there – 300, 600 or something, so I had 250 extras. What was interesting about the place that we filmed was that it was elaborate. There were lots of passes around and then this little yard where everything takes place. And I really wanted to put people everywhere, so I asked five of my friends, who were also directors, to control a group of extras in different areas of the location. There was a six-person communication there. And most of the extras weren’t actors; a lot of them we just found around because we didn’t have a lot of money for this film. Everybody worked almost for nothing.

In each group, I put some actors to help the directors work with the extras. It took two days of rehearsing – obviously not with everybody, but with the actors playing the Nazi collaborators, the nationalists, and also the Jews. While we were rehearsing those two days, I figured out how to choreograph the camera, how it should follow the main character.

You know, we had running horses, fire, and lots of people. It took 20 takes. 20 8-minute takes to make the shot.

Your film differs from Skema’s short story in several respects, including details as foundational as the setting. This was a story that originally took place in America, but you’ve brought it back to Lithuania. Can you talk about that decision? What did the Lithuanian backdrop add to Andrius’ story that an American one couldn’t?

Jurgis Matuelevičius: Well, the main character stayed where he murdered. Everything is really nearby. The main thing, though, is the historical context. Andrius goes from one regime, the Nazi regime, to another, the Soviet. So, it kind of portrays his character as a puppet, as a coward. I really pointed to that.

My country’s context was really important for me as I was doing the research on the massacre and later, the Soviet’s time in Lithuania. I found so much detective information, and I really wanted to use that in the film. So, that’s why we had the KGB theme, the agents who are always listening to the conversations. It was real. I even listened to some of these recordings from when the KGB was following actors or directors, artists. It’s not so far from the truth.

Skema put his story far away. It’s kind of a diary from a psychiatric hospital, so I didn’t want to stray too far from that. I wanted to put that feeling of paranoia in the film, and I wanted it to speak like a diary, where the pages of his life reoccur.

When and why did you decide to add the KGB detective story to Isaac? Because that was obviously something new to the short story as well.

Jurgis Matuelevičius: Skema, the writer, I read all his works. And he has lots of dramas about KGB personnel. He had this one drama about Lithuanian nationalists who is interrogated by a KGB Lithuanian. So I wanted to make a mix of his writings and his characters and put it into my film. Plus, I really wanted to make a detective story.

The KGB thing helped me show how people felt being under regimes for so long. Our country, for 50 years, was under this big hand: Stalin, Khrushchev, Brezhnev. And I think the KGB really portrays that well, how people lived in distress and couldn’t speak freely. Then there’s this guy, this director, who comes from the USA and knows what free speech is. He felt it. And he tries to bring just a drop of that freedom back into our country, and he’s crushed.

What’s so interesting, in my opinion, about the KGB story is the contrast between the agency’s brutality and overbearingness and the detective’s obsession with getting to the bottom of a decades-old massacre. He seems so passionate about righting this specific wrong. Writing the character, was it weird or odd for you, knowing the history of the KGB, to give a KGB officer this sort of heroic task?

Jurgis Matuelevičius: I portray as an obsessive maniac. Well, that was the main idea, to make him like a maniac. I read this story in the KGB archives about one agent who tried to get this award the KGB was offering people who looked into the pogroms and massacres of Jews. It’s like an honorable premium of Israel. So, that inspired me to write the character.

The contrast, as you said, is the point. He looks like the hero, but he’s an aggressor. That’s the point of all oppressions, and especially the Soviet Union. They portray themselves to their people as heroes. We had the Stalin or Lenin awards of “Best Factor Worker,” where everyone, the working man and the working woman, was portrayed as heroes. That was a big part of our history.

The film mentions three transitions of power in Lithuania: the initial Soviet takeover, followed by Nazi occupation in 1941, and then the Soviet return in 1945 and into the 1960s, where most of the film takes place. How would you describe the effect of this political whiplash on Lithuania, and how did you want to translate that effect into the film?

Jurgis Matuelevičius: In four years, we were occupied by Soviets, Nazis, and Soviets again. When that happens, something clicks in your mind and you start to believe no one. You think, “who cares?” When Nazis come, they kill your neighbors. When Soviets come, they send your sister and brother to Siberia to work in the camps. I really wanted to portray this chaos that happened in my country inside my main character’s head.

Because he was afraid to die himself, or to be sent to prison, he acted from fear. He acted the way he acted and he became a puppet of these regimes.

There was a lot of propaganda from both sides. The Nazis thought that the Soviets were murderers, including the Jews that were working with the KGB. And the Soviets were moving in a direction against Nazis and any nationalists. In this context, people felt they needed to fight for their country, but also, for freedom of yourself as a human being. It’s really a complex period of our history.

You’ve talked about the complicated, almost revisionist relationship Lithuania has with its own past, especially during this time period. It’s almost like a denial of sorts. Do you expect any kind of backlash from Lithuanian audiences against this film?

Jurgis Matuelevičius: Yeah, yeah. I think every country has indecent parts and indecent people in their history. There are no exceptions. I’m not saying that we, as a country, participated in the Holocaust. I say that we had people who were collaborators of Nazis. We also had people who helped the Jewish population to escape. It’s the same as with the Soviet regime.

But I think that the main problem and the main question here rests in one’s morality. Do you have the right to kill? Of course, the answer is no.

It’s more about a human being himself, not the historical context. That’s why I put in so many different things to show that it’s my perspective. I put more modern music in it; the people talk in modern language; there are lots of different details that show you it’s a historical drama put in a fictional environment. It’s like a bad dream from which you can’t wake up.

Isaac had its U.S. premiere at the 2021 Slamdance Film Festival.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Join now!