How the United States and Soviet Union Embarked on a Macabre Surgical Arms Race

This story is excerpted and adapted from Brandy Schillace’s Mr. Humble and Dr. Butcher: A Monkey’s Head, the Pope’s Neuroscientist, and the Quest to Transplant the Soul, published in March 2021 by Simon & Schuster.

A grainy black-and-white film shuddered across television screens in the last days of May 1958. A man in a long white lab coat gestures to a corner, where a figure waits, shadowy and indistinct. He leads the creature into the light of a courtyard, revealing a strange composite body: a large mastiff dog with a strange and cockeyed mini-body projecting from his back. The second head lolls to one side, tongue panting, legs hanging askew over the shoulders of his larger mate. Offered a saucer of milk, both heads drink for an applauding group of onlookers; close-cut angles reveal the bandages and stiches. Cerberus, named after the mythical three-headed hound of Hades, parades before the camera, a surgically remastered two-headed dog.

No one speaks in the footage; if they had, most of the wider world wouldn’t have been able to understand. The film and the physiologist behind it, Vladimir Demikhov, emerged from behind the Iron Curtain, inexplicable, macabre, and without much context. And yet the flickering images sent a tremor round the surgical world. The footage reached as far as Cape Town, where Christiaan Barnard (already working on the first human heart transplant) felt compelled to try and repeat Demikhov’s experiments. (He succeeded but the dog died, and he had an effigy stuffed and paraded about campus.) News also reached the surgeons at Boston’s Peter Bent Brigham, though Joseph Murray, the young doctor on the cutting edge of early transplantation efforts, wasn’t convinced of its veracity. Might it not be a hoax?

Some dozen years before, Russia had released another film, its first ever produced for Western audiences, called Experiments in the Revival of Organisms. The film presented medical centers with whole departments dedicated to isolated organs: hearts beating on their own, lungs breathing by use of a bellows, the head of a dog supposedly kept alive by machines. This motley circus belonged to Sergei Bryukhonenko, a man both hailed for his groundbreaking research into blood transfusion and later reviled (outside Russia) as a surgical charlatan. His experiments had been half-real chimeras. While he had successfully isolated certain organs, many of his other claims served only as propaganda, suggesting that Russian science would lead to human immortality. That didn’t keep his footage from sparking fears of reanimated bodies, of life artificially extended beyond the grave—and the Cerberus film wasn’t as easily dismissed. In May 1958, Demikhov gave a public lecture in Leipzig, East Germany, and even performed several heart transplant surgeries (on dogs) in Leipzig by that December. In 1959, he would take part in the XVIII Congress of the International Society of Surgery in Munich. In these presentations and papers, Demikhov revealed that he had been performing these kinds of transplant operations for four years, the first taking place in February 1954—before Murray ever transplanted a kidney (the world’s first successful one, between twins, later that year), before the West knew it was possible to transplant anything more than skin. “What else,” Western medicine asked, “might the Soviets have done?”

Many Stalinist laboratories operated quietly outside Moscow. The work remained shrouded in mystery, and unwarranted disclosure could mean imprisonment (or worse); scientists in the same lab limited conversation to the weather and the state of roads, making progress on shared projects difficult and discouraging. That anything so gripping as film footage could escape from Russia unnoticed beggared belief. No—this was surely intentional. But what did it mean? The “leak” (if so it was) followed hard upon the famous words of Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, who told Western ambassadors gathered at Moscow’s Polish Embassy in 1956: “Whether you like it or not, history is on our side […] We will bury you!” He meant to impress the assembly of the ultimate victory of socialism over capitalism. Soviet supremacy, he insisted, was “the logic of historical development.” Demikhov’s work sent the same kind of message, a warning to the West about the superiority of Soviet science. It shocked and dismayed, but it also begged for an answer. How would the United States meet such an unusual challenge? With only a spare few minutes of film, Cerberus and its surgical creator would inaugurate one of the strangest contests of the Cold War.

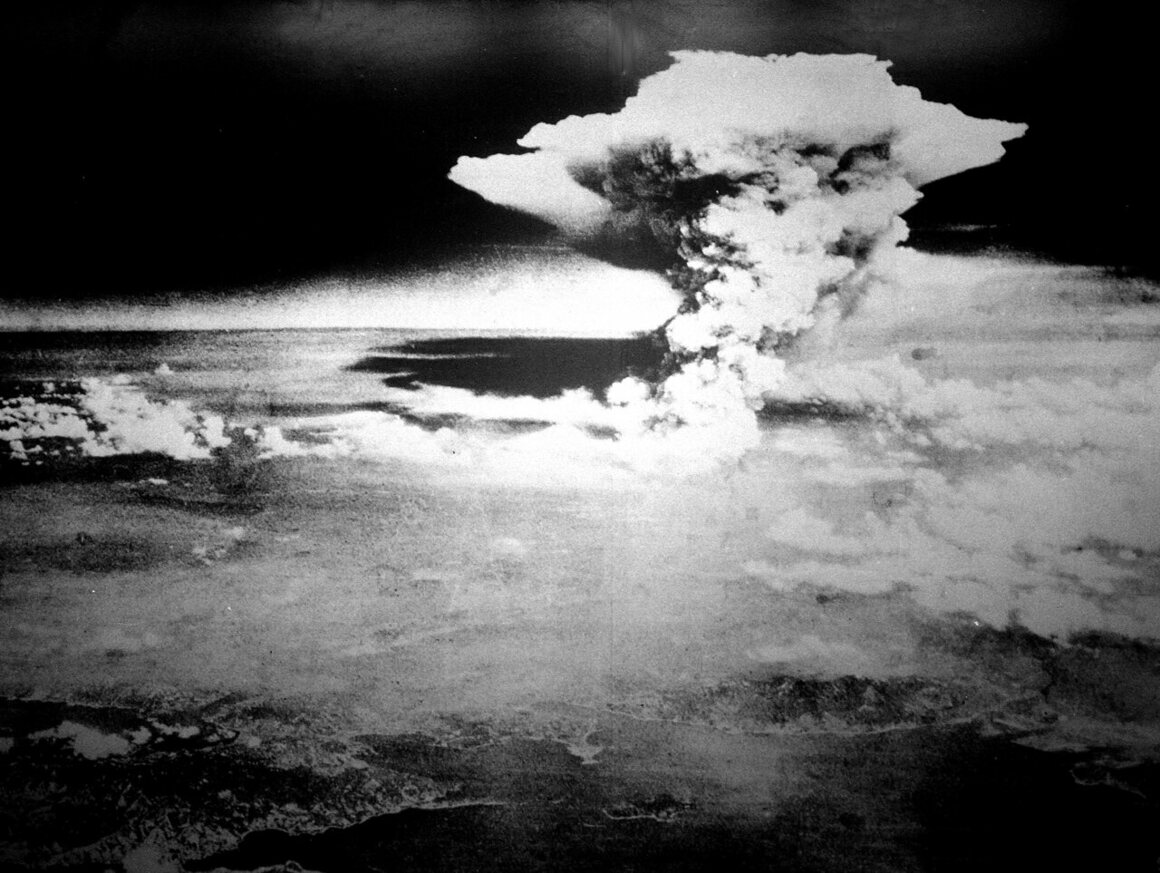

We have, all of us, grown up in a world of nuclear possibility. As late as the 1980s, students still performed air-raid drills, hiding beneath flimsy desks while pop icons such as Sting released singles hoping “the Russians love their children too.” The military-industrial complex so completely anchors our understanding of the last century that it’s only with difficulty that we imagine a world before it. Yet little of that extraordinary military apparatus existed before Enola Gay dropped the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The publicly given reason for doing so was to end the war, though firebombing campaigns had already ravaged Japanese cities, and Japan’s hamstrung navy could no longer perform major maneuvers. Historians continue to debate whether unleashing radioactive warfare had been a necessary step, but one thing remains certain: The atom bomb’s sheer destructive force, mysteriously expanding from the tell-tale mushroom cloud, made it the most powerful weapon of psychological intimidation yet invented. It sent a fearful message to the world about the United States’ combined military might and technical superiority. That was, after all, the point.

The awesome, annihilating power of the bomb did more than end a war: It changed the role of science, which became, writes Cold War historian Audra Wolfe, a tool not only of war but of foreign relations, too. A climate of optimism developed among the American public, built on the belief that science had won the war for us, fostering a relaxed attitude toward our enemies and competitors. The United States, after all, controlled the brain trust of scientists, as well as the raw materials (stockpiles of uranium). Some researchers and government officials held less rosy views about either American superiority or the safety of its exclusive control. The most conservative estimates suggested at least a five-year monopoly on atomic ability. They were wrong. Soviets began testing the atom bomb by 1949, and the gap closed faster as time went on.

How could a war-torn country, still deep in debt, produce results so quickly? The question haunted American officials. Mark Popovskii, a Russian journalist forced to flee to the United States for his reports about the Soviet government, described military laboratories “springing out of the ground like mushrooms,” while Higher Examination Boards turned out up to 5,000 doctoral degrees per year. This wasn’t mere saber rattling. If Russians could prove superiority in science and technology, they could control the temperature of the Cold War. If my science wins, went the argument, then that means my ideology’s won, too—and both sides believed only one system could prevail.

Across America, surgeons’ changing rooms, the medical equivalent of the water-cooler, buzzed with rumors about Russian medicine. Both Joseph Murray and Robert White, a neurosurgeon also deeply interested in transplantation, had witnessed firsthand how military science could influence and catalyze medical science, reallocating resources toward plastic surgery to heal wounds and the study of pathogens that might make troops sick. Ever since the war, Russia’s military tech “had come so far so fast… we wondered if there was some spill over in medicine,” White would later explain, remembering the wild speculation of those days. “Maybe behind the curtain there were research centers that had cured cancer or found ways to replace the blood with artificial solutions.” American doctors were afraid the Russians were winning. And through the occasional films, publications, and propaganda speeches that reached the West, Russia certainly tried to give that impression.

After the war, experiments in medicine redoubled. The Soviet Institute for Brain Research at Leningrad State University researched telepathy, or “biological communication,” and attempted training programs to boost military personnel’s precognitive abilities. Fearful rumors suggested the Russians had even mastered psychokinesis for guided missiles, or that they dabbled in the occult. It might seem remarkable—even ridiculous—but the United States took these paranormal possibilities seriously. American scientists couldn’t afford to be skeptical; no one really knew for sure that the Soviets hadn’t made such breakthroughs. After all, a few decades earlier, splitting the atom had seemed just as magical, mysterious, and practically impossible.

The postwar era operated on two guiding principles. On one hand, incredible hope for scientific (even pseudo-scientific) possibility; on the other, an increasing dread that the Soviets would get there first—the science fiction trope that the “enemy” would somehow beat the “good guys” through mastery of technology. And so, when the Demikhov footage appeared, it acted almost like the mushroom clouds off distant islands. Whatever else occurred behind the Curtain, the Russians were making monsters.

In 1959, journalist Edmund Stevens of LIFE Magazine received an unusual invitation: He and American photojournalist Howard Sochurek would be welcomed to document a surgery conducted by Demikhov, a physiologist without an MD who had been engaged in ambitious, even reckless surgical experiments. Stevens, who lived in Russia, had won a Pulitzer in 1950 for a series of articles for The Christian Science Monitor titled “Russia Uncensored,” about life under Stalin. Despite being an American by birth, Stevens sympathized with the country he’d called home since 1934.

Stevens described Demikhov as “vigorously decisive,” a man in utter command. The morning of the surgery, he presented his assistants and surgical nurse in turn, but the journalists could not help but concentrate on the “patients,” one of whom was barking incessantly. Shavka, a “perky little mongrel” yipped excitedly, floppy ears and pointed nose actively twitching and alert. Her normally shaggy hair had been shorn away about her middle; she was soon to lose her torso and lower extremities, including all capacity for digestion, respiration, and heartbeat. Already anesthetized, Brodyaga, or “Tramp,” lay upon the table next to her. He’d lost his freedom to dogcatchers, and would now serve as Shavka’s “recipient.” While the journalists marveled, Demikhov called over another dog. Named Palma, she had a series of serious scars upon her chest from an operation six days previous; Demikhov had given her a second heart and altered her lungs to accommodate it. She happily nuzzled him, wagging her tail. “You see, she bears me no ill will,” he said, as if answering Stevens’ misgivings.

Demikhov scrubbed up for surgery on Shavka and Brodyaga. “You know the saying,” he remarked in Russian. “Two heads are better than one.” Shavka, who had continued to bark all the while, was at last put under a heavy narcotic. To the world, this was Demikhov’s second two-headed canine surgery. In fact, it marked his 24th—two dozen surgeries (on 44 dogs) in five years. The entire procedure took less than four hours. His first, in 1954, had taken 12.

Finished with the grisly work, Demikhov removed his gloves. The idea for a two-headed dog, he explained calmly, came to him 10 years earlier. Now, working on dogs seemed almost passé. “I have news for you,” he announced. “We are moving our entire project to a wing of the Sklifosovsky Institute,” Moscow’s largest emergency hospital. They had outgrown the “experimental” stage, he claimed, and it was time to move on to human transplants.

Did Demikhov truly plan to operate on people, even though science had yet to find a reliable way to make non-twin transplants work? “Moscow is a huge city where hundreds die daily,” he added. Why shouldn’t the dead serve the living? Demikhov gave Stevens a rare smile, and revealed he had a test subject already, a woman of 35 who had lost her leg in a streetcar accident. He planned to provide her with a new one. “The main problem will be joining the nerves so that the woman can control her movements,” he added. “But I am sure we can lick that too.”

Shavka and Brogyaga would perish only four days later. Demikhov didn’t think of this as a failure, however. Far from it. Back at Brigham, Joseph Murray, reading Stevens’s piece in LIFE, balked; the tissues Demikhov planned to transplant could never function properly, he grumbled. The dogs, after all, would have eventually perished from the rejection of the foreign tissue. Murray was now working hard on anti-rejection drugs, though he wouldn’t have much success until the following decade. Demikhov couldn’t expect favorable results “unless,” he added derisively, “the Russians have made some breakthrough we don’t know about.” But as with the launch of Sputnik, no one could be certain they hadn’t.

Enormous streams of funding poured into research and development. Since Russia put up the first satellite, the United States would launch a better one. Since Russia put a dog in space (Laika, on Sputnik II), the United States would launch a chimp (named Ham). Stevens’s article proved Demikhov’s proficiency with head transplants, and in the same spirit of creative one-upmanship, the National Institute of Health in America began funding experimental laboratories. What the Soviets could do with dogs, went the logic, we could do with primates. And what could be done with primates could be done with humans. The United States and Soviet Union had embarked upon an inner space race—decades of surgical brinksmanship.