Solved: The Mystery of a Lonely Human Skull in an Italian Cave

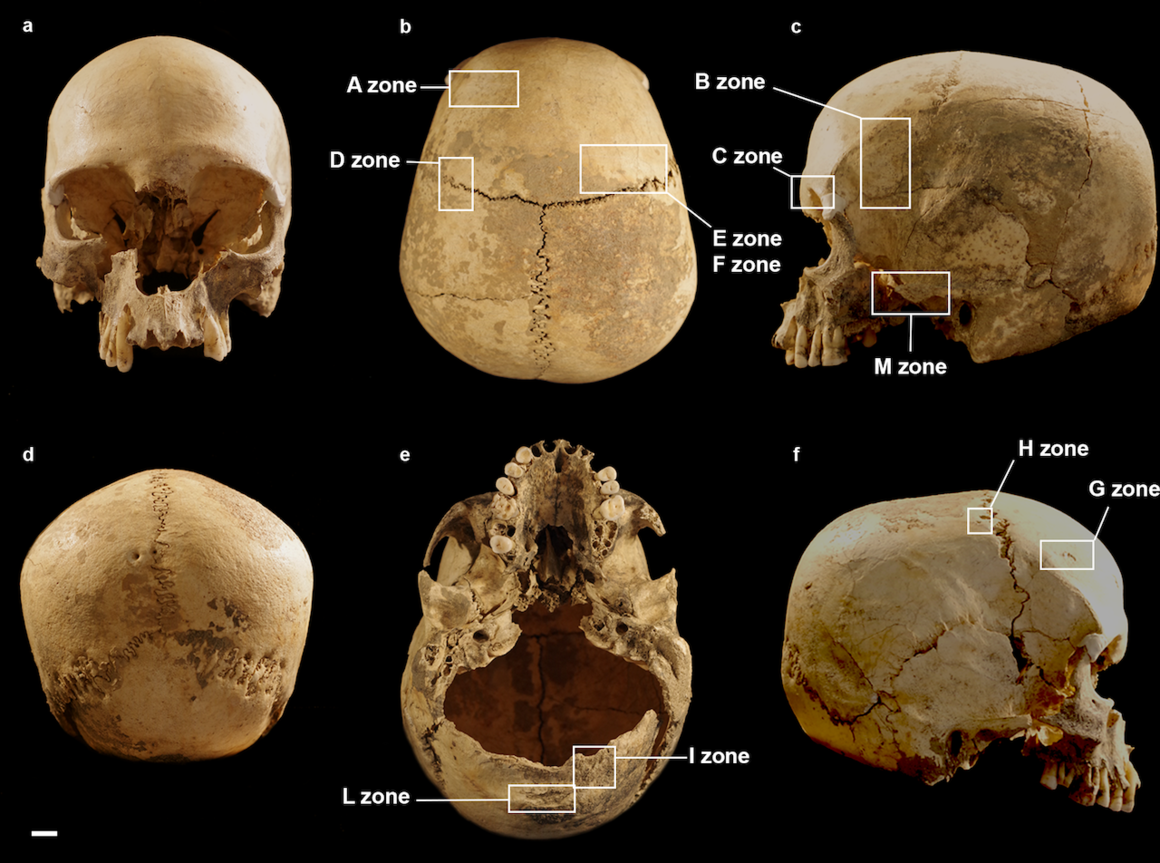

The find was perplexing. In 2015, cave explorers inching through a vertical passage in northern Italy’s Marcel Loubens Cave discovered a partial human skull. The cranium was missing its jawbone, and sat upended on a slim ledge near the top of the shaft. No other human remains were found there, and there was no sign of who might have placed the skull there, or when, or why.

Marcel Loubens Cave sits near the center of Dolina dell’Inferno, or Hell’s Sinkhole, a massive karst formation riddled with narrow passages carved into the porous rock by water over millennia. The cranium’s location was particularly poignant: The cave is named in memory of the speleology legend Loubens, who died while exploring a system in his native France in 1952. Was the skull the remains of another adventurer who met a tragic fate? The shaft where the remains were found sits within a meander, caver-speak for a winding passage created by an earlier flow of water. This proved to be the first clue to what befell the individual.

In June 2017, a team of about a dozen volunteers, including University of Bologna archaeologist Lucia Castagna, worked their way through the narrow spaces to where the partial skull waited for them, undisturbed since its discovery. The meander leading the team to the skull is about 85 feet underground, and less than a foot wide in places. The difficulty of negotiating its treacherous turns has earned it the name Meandro della cattiveria, or Maze of Malice.

Shortly after her death from unknown causes, the woman’s body was prepared in some way, likely defleshed and dismembered. Separated from the body, the skull appears to have fallen, or been washed into, one of the area’s many sinkholes, possibly during heavy rains or a mudslide. From there, the cranium was carried along by a coursing underground waterway before it got lodged in the shaft. Over more than 5,000 years, continued erosion of the rock around it moved the bone into the position where cavers found it.

Stinnesbeck and his team recently performed a similar investigation on Chan Hol 3 woman, a partial skeleton found near Tulum, Mexico, in a submerged cave system. The remains, almost 10,000 years old, are among the oldest such finds in the Americas. Using methods similar to those employed by the Italian team, the researchers determined that she had survived disease and head trauma before being placed in the cave, which was dry at the time due to lower sea levels.

“In many aspects, [the Marcel Loubens Cave cranium research] resembles our work on the Chan Hol 3 woman,” Stinnesbeck says. “We both tried to shed light on the life and death of these poor individuals. As scientists, we document our data as objectively as possible but, as a human, we are well aware of [their] fate.”

Belcastro agrees, pleased her team was able to solve this very cold case, but, she says, “sad to think the long journey her corpse, or part of her corpse, had until her final and lonely resting place.”