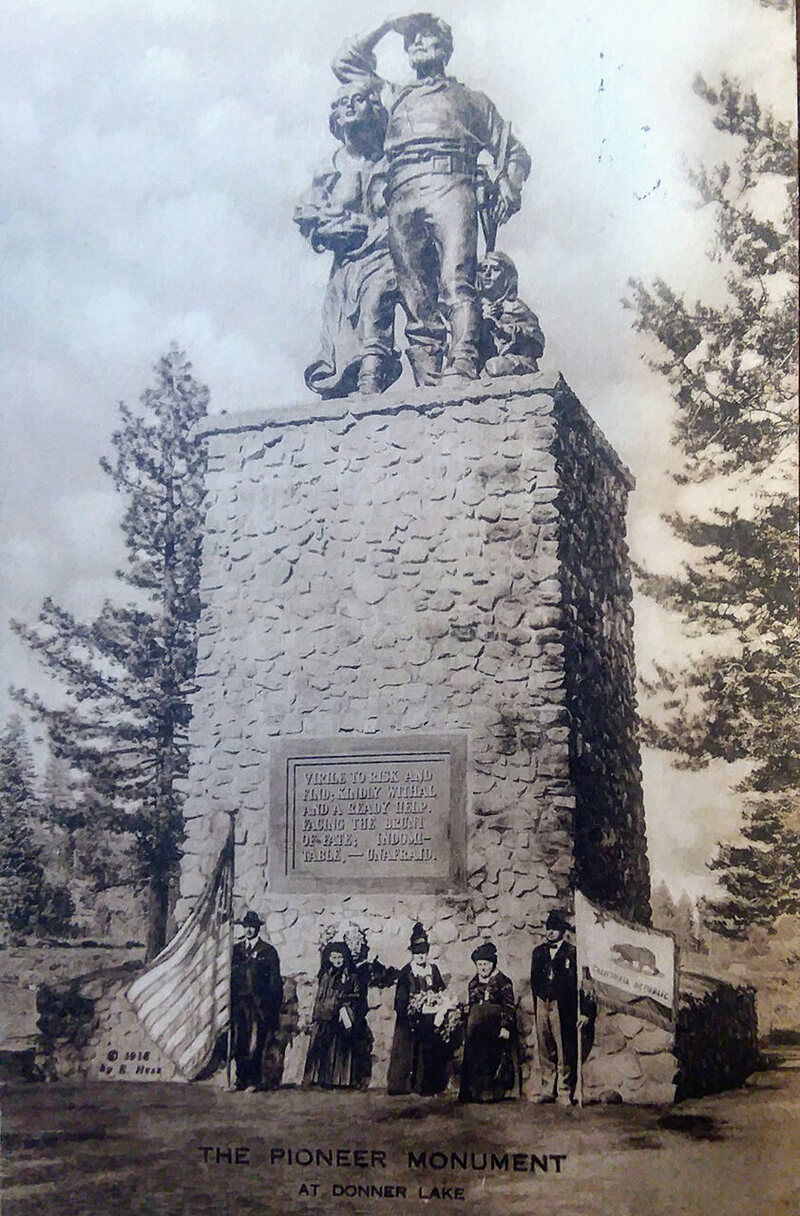

Retracing a Donner Party Path, Nearly Two Centuries Later

On the second day of their December 2020 voyage through the punishing Sierra mountain range, the four team members of the Forlorn Hope Expedition woke to find six inches of snow had piled on their tents, and more was falling. They made oatmeal on their camp stoves and hustled to get moving. The previous day, they had covered ground that a group of pioneers in the winter of 1846-47 had needed a week to accomplish—and they would ultimately traverse 100 miles in five days, versus the pioneers’ 33. Both parties departed on December 16, with 174 years between them. The difference? Parkas, plenty of daily calories, tents, state-of-the-art snowshoes—and, most importantly, a researched path.

“This is not a re-creation or reenactment,” says Bob Crowley, a member of the 2020 expedition. “It’s a reprise. Our main thrust is to honor those ordinary people looking for a better life in California, who suffered from bad luck and bad karma.”

The original Forlorn Hope members had set out from the larger Donner Party—a group of emigrants traveling from the Midwest to California by covered wagon across rugged terrain—in a desperate bid to get to shelter and food at Johnson’s Ranch in Wheatland, California. The ranch was then the largest outpost between Fort Bridger in what is now Wyoming and Sutter’s Fort in Sacramento. Harrowing details abound of this band of 17—the youngest just 12 years old—who traveled with nothing but what they could carry. The sole person who knew the way out, Charles Stanton, succumbed to snow blindness and exhaustion. He sat to smoke his pipe and never rose again.

When going forward seemed impossible for the 19th-century group, thoughts of those left behind starving proved inspirational. “Mary Graves said she couldn’t go back to hear the cries of her little brothers and sisters,” says Kristin Johnson, a Donner Party historian and author. “She sort of reminded everybody of what they were doing this for.” For 36 hours, huddled under a dome of blankets, the emigrants sat through a blizzard. They drew lots to kill someone for food but couldn’t bear to follow through. After six hungry days, they turned to the bodies of four that had perished, weeping as they ate. Later, William Foster suggested murdering Luis and Salvador, two Native Americans from Sutter’s Fort pressed into service as rescuers, for food. Tipped off, the two escaped in the night but a week later, Foster tracked them by their bloody footprints and shot them, a well-documented but little talked-of chapter in the tragedy. Assisted by Nisenan Indians in the final stretch, only seven survivors arrived at Johnson’s Ranch.

Crowley and fellow 21st-century expeditioner Tim Twietmeyer sleuthed for seven years to determine the pioneers’ steps, combining a love of history and trail running (all four 2020 participants are ua-distance athletes). “We assumed there was a map,” Crowley says, “but there didn’t appear to be anybody who knew where they went.”

The two created a spreadsheet for each day of the earlier trip, looking at historic accounts of the trail that sometimes contradicted each other or were unclear. As an uarunner, Crowley knows what it’s like to hallucinate from exhaustion and posited that the trekkers would have always chosen the path of least resistance: downhill, including a wrong turn that cost them days. Crowley believes his and Twietmeyer’s course is 85 percent accurate. “One can never be 100 percent because there was no forensic evidence. So 85 is a generally used percentage representing a well informed, research postulate,” he says.

One reason it’s hard to retrace the 19th-century route is that the 1800s journeyers traveled atop snow that then melted. But people have made efforts to reconstitute it, as well as that of the larger Donner Party. Starting in the 1920s, amateur historian Peter Weddell spent his vacations mapping and marking the Emigrant Trail with wooden signs, most of which are now gone. In the 1940s, trails enthusiast Wendell Robie nailed signs to trees while on horseback. “They’re so danged high nobody took them down,” says Crowley. Others have been erected by local groups.

However, not all signs are trustworthy. One purports to mark where Charles Stanton sat down for that last draw on his pipe. “The Donner Summit Historical Society doesn’t know who erected the sign, nor is there any indication as to the source,” says Crowley. “What we do know, based on numerous historical accounts, is that it’s miles from the correct location at Yuba Bottoms.” Nonetheless, the recent expedition paused there to read a poem Stanton wrote his deceased mother.

Johnson’s Ranch—the group’s final stop, which saw 100 wagons a day in 1849—is itself a transitory marker. The remote ranch sits on private land that is slated to become a housing development. Bill Holmes, project manager at the Wheatland Historical Society, Trails West, and Oregon-California Trails Association, hopes that at least its historic sites can be preserved. Those include the location of the adobe where the Forlorn Hope received first aid, the Bear River crossing, a hotel site, remains of Camp Far West—a military outpost created to protect Gold Rushers—and its cemetery and two miles of wagon train ruts. The ranch and hotel sites are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Over the years, Holmes and interested buddies Bart Johnson and Joe Waggershauser have hired archaeologists, brought out cadaver dogs to detect human remains, and engaged a master’s student to design interpretive panels. A guerrilla historian, Holmes also cut up a redwood table to create signs that he installed at Johnson’s Ranch—without permission. “When we put up these signs, we’re kind of sending a signal: ‘We’ve got your signs up; where’s your road?’” he says. Holmes works with the National Park Service and the National Forest Service to ensure they know where the landmarks are, “but there’s lots of turnover,” he says. The ranch’s land manager, Francisco Paredes, has been an ally. When farm equipment was set to plow a field that held wagon ruts, Paredes alerted Holmes so the work could be stopped. Holmes designed a public access road, parking lot, and one-mile trail connecting the sites that could be established if the ranch owner agrees. “So far, he hasn’t said no,” says Holmes.

Like their predecessors, the modern expedition faced trouble. Landowners reneged on access, leaving them without a place to pitch their tents one night until they placed frantic phone calls. Falling snow soaked their clothes, “a little hint” of what the prior folks endured, says Crowley.

For Twietmeyer, the worst obstacle was something the emigrants did not face: whitethorn, “a miserable shrub with thorns.” This bush—which only grows after fire—caught their snowshoes and tripped them. “Every ten minutes, we’d hear [fellow expedition member Elke Reimer] yell, “Man down!’” he says. Bison and cows chased them, a circumstance the starving 1800s party would have welcomed.

Fording the American River, thigh-deep in icy water, made Reimer think of her historic counterparts in petticoats. “Are you going to strip down to nothing to have dry clothes on the other side, or deal with freezing clothes [that are] heavy and cold?” she wondered. She battled toe cramps and heel blisters, but notes that the contemporary group had it better than the first trekkers, whose footwear actually disintegrated. “We thought of them the whole way.”

The 2020 group carried tribute cards with an image and biography of each Forlorn Hope emigrant. At Johnson’s Ranch, they laid them on the ground at the adobe site, constituting a reunion of sorts for the people who went separate ways afterward and never returned. “We felt a presence with us and a responsibility to finish the mission,” Crowley says. Descendants of almost every survivor have contacted them, and Crowley hopes the expedition website can forge further connections.

The team took an approach to the Donners that is empathetic rather than ghoulish, and reprising the route provided partial insight into the horrors that the 19th-century travelers encountered. As 2020 expedition member Jennifer Walker Hemmen says, “Until you lie down in the snow in cotton and wool, there’s no way to understand.”