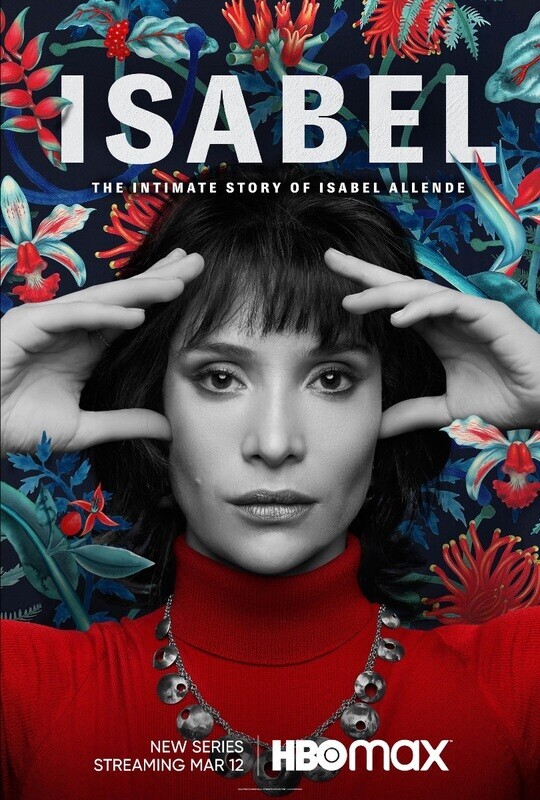

HBO’s Isabel is a Powerful Look at an Influential Life

Latinas are supposed to be quiet—or at least, that’s what you might have heard. Historically, we’ve attempted to silence our own with “advice” like “calladita te ves más bonita” (which loosely translates to “you’d be prettier if you talked less”). It’s not exactly a feminist sentiment and it’s reinforced externally by Hollywood’s portrayal of Latinas—we’re rarely on screen and when we do appear, we’re usually in the background, silent props to help the Anglo characters along.

That’s why HBO’s three-part miniseries “Isabel” is significant; it lifts up one of our strongest voices in Chilean writer and icon Isabel Allende. In her, we’re reminded not only that Latinas have never been silent but also that our voices matter. For those unfamiliar with Allende (maybe you didn’t major in English, I don’t know), she’s canon. She’s published 24 books, sold more than 70 million copies, and populates syllabuses across the country. Going into “Isabel,” I’d read some of her novels and thought of her as a literary God akin to Mark Twain or Ralph Waldo Ellison.

“Isabel,” like all good biopics, reveals the person behind the legend, humanizing its protagonist and reminding viewers that the path to greatness is never assured and rarely foreseen. It has plenty of literary easter eggs for the author’s fans, particularly when recounting Isabel’s childhood. And the miniseries shines in dramatizing the creative process. We see Isabel starting her writing career and floundering in her first editorial meeting, unsure of what to pitch or even where to start. At home, she gets an idea to satirize the types of (ineffectual) husbands and soon she’s scribbling away. Her editor encourages her and she grows in confidence, penning one piece after another. It’s an inspiring case study on how someone starts writing, finds inspiration, and hones their craft.

Allende’s writing is political and her life is too, with “Isabel” portraying her activism as part accident and part heroism, avoiding the temptation to lionize her. The most obvious example occurs after the assassination of Allende’s uncle, Chilean President Salvador Allende, in a coup that installed General Augusto Pinochet as Chile’s brutal dictator. Isabel goes to check on one of her colleagues from the magazine and sees the violence inflicted on him by the new regime. Worried for his life, she helps him get out of the country. And she keeps helping people escape, while knowing that doing so endangers her family, until her children are kidnapped in a warning from the state.

More than once, we see Isabel make this choice to put her goals over her children—whether it’s in resisting Pinochet or fighting for her own happiness—and I appreciate how the series doesn’t demonize or romanticize her for it. Instead, it lets these choices breathe, showing how they eventually make her the writer she becomes. Take how they portray her exile in Venezuela as a difficult but not defining period. She can’t find work there, falls into a depression, has an affair. And she abandons her kids, leaving them behind to see if she has better luck in Spain with her lover. But “Isabel” refuses to damn her for it. Yes, it shows the pain this choice wrought but it also connects it to our heroine’s later success. For it is after she returns to her family, shamed but not broken, that she begins writing her first book, La casa de los espiritus/The House of Spirits. Arguably (and “Isabel” does seem to present it this way), one thing leads to the other; her own complicated relationship to her family allows her to plumb the depths of her nation’s and personal history and turn it into a masterpiece.

“Isabel” extends this feminist perspective to its subject sex life, taking a more candid approach than we’re used to seeing. We follow Isabel struggling to make things work with her husband post-affair but he’s not interested in her advances. After they divorce, she does some bed hopping, which the show depicts in a delightful montage, the type women’s sexual exploits rarely get (particularly when they’re in their 40s). She does remarry but again, “Isabel” presents this second pairing as more of a happy accident than any sort of happily-ever-after (in real life, she’s divorced from him too but the miniseries doesn’t get into that).

Life goes on and having a husband doesn’t inoculate Isabel from tragedy. She writes more and is more successful but her daughter dies at 29 from complications of a genetic kidney disease. Again, we see Isabel fighting, arguing with the doctor, her ex-husband, anyone in her path (the current husband isn’t much of a force here). Eventually, she must accept the tragedy, made more so by her own complex feelings around motherhood. It’s beautifully sad and terribly poignant (I may have cried; I certainly wanted to look away as a mom myself), but it makes Allende human, subject to the same cruelties of fate as the rest of us.

In the end, the miniseries makes Isabel Allende feel both exceptional and relatable, her story tragic and triumphant. Like her writing, “Isabel” is personal and political, mixing the two to tell the story of a whole human being who faces a harsh world bravely but imperfectly. The result is inspirational, a reminder of the challenges Latinas continue to face and also a pathway to transcending them. It’s just the thing you want to watch after rolling your eyes at someone who says, “calladita te ves más bonita.”

Available on HBO Max on March 12.