For Decades, Italians Have Salvaged Old American Military Uniforms in This Open-Air Market

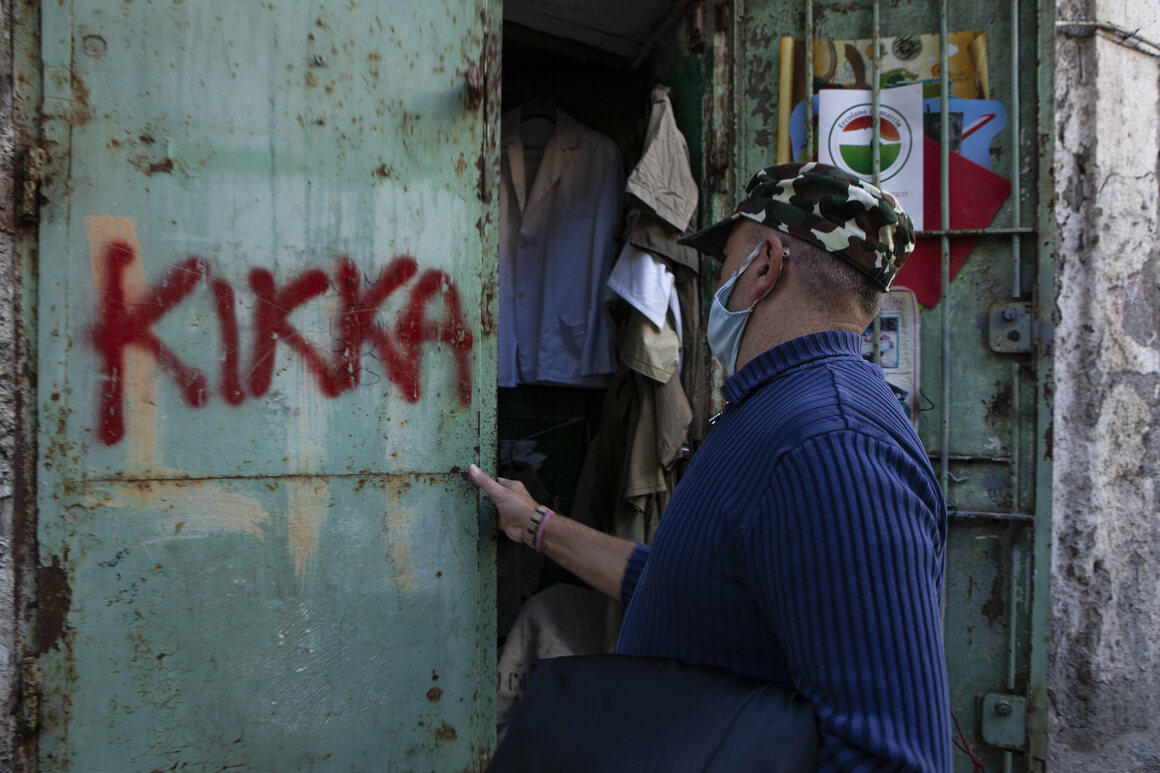

Early each morning, keys turn in locks on the ground floor shops along Pugliano street in the Italian town of Ercolano. Doors open to reveal shiny sequin dresses, furs in a range of browns, and jeans from the 1970s—plus a slew of military uniforms, displayed on hangers, dangling from boxes, or draped on white sheets. Many of the clothes worn by American soldiers who stormed Italy in the 1940s now live here, at one of the largest markets in Southern Italy.

When American convoys passed through en route to northern Italy, in 1944, locals in Ercolano and elsewhere intercepted the troops and stole clothes to resell. Then, when the war ended, American troops left some clothes and supplies behind in warehouses outside of Naples because it was cheaper than carting them home. “Wars usually bring famine and destruction, but it also brought something we could build survival from,” says Ciro De Gaetano, one of the shop owners in Pugliano Market.

In the postwar years, these clothes and other items were vital for residents. “After the war, there was nothing,” says De Gaetano. “There was the need to find clothes, but no supply chain. People bought what they could find and dressed in secondhand clothes from the U.S.” Salvaged materials became consumer goods: American parachutes made of silk, for example, were torn up to make underwear sold along Pugliano.

As part of the Marshall Plan, a U.S. effort to provide economic aid to devastated Europe, truckloads of bales of used clothing arrived in Ercolano, sent from American warehouses, tailors, and laundries. Locally known as the “river of gold,” the market on Pugliano provided jobs to around 4,000 people. “Some would get temporarily rich, because they would find valuables and money forgotten in the pockets” of clothes, says Rosario Losa, an Ercolano resident whose grandfather recounted the tale.

For decades, the market has attracted shoppers from Naples and neighboring cities. Years ago, young people took the regional train to get to this little town, one of the first places in Europe where jeans were sold. “You’d go early in the morning at dawn, [when] there were unopened bales of used clothes ready to rummage in,” says Francesco De Lorenzo. He found a pair of roller skates there in the 1970s, when the market was a place to find objects that weren’t yet widely available elsewhere in Italy.

Now, visitors arrive in different ways, flocking by scooter, car, or bus. But the most-wanted items remain original military uniforms, especially khaki or camouflage button-up jackets. The name of the soldier who owned the garment appears on embroidered tags sewn above the right pocket, creating a link with an unknown person on the other side of the world.

Beyond the battleground and daily wear, the military clothes also reached cinema screens. Production designers and costume designers for films and plays come from Rome, more than 140 miles away, to rifle through the hangers in search of pieces for productions set during or after World War II. Clothes from the market have appeared in movies such as Kiss Me First and One Hundred Steps. Italian fashion designers are also drawn by the vintage clothes, which can spark inspiration for new collections.

Though some sellers have diversified their offerings—Ciro De Gaetano specializes in vintage women’s clothes and wedding dresses, and sells to boutiques in London, the U.S., and Germany—others inherited family businesses and kept them intact. Daniele Lettieri took over a third-generation military clothes business started by his grandad, Carmine, over 70 years ago.

The COVID-19 crisis has pushed the market into the toughest time it has seen since 1980, when an earthquake nearly destroyed the city. This time, some shop owners have moved their businesses online. They look through their piles at the request of faithful customers who reach out in search of something special, but sales to boutiques abroad have mostly ground to a halt. The pandemic’s collateral damage on artistic endeavors has trickled down to the market, too: “We have stopped receiving requests from film production, but most of all from theaters,” says Lettieri. The sellers eagerly look forward to the end of the pandemic, and the return to business as usual.