How Cold War Fears Helped Create Helsinki’s Subterranean Paradise

Nearly 200 miles of tunnels snake beneath Helsinki, providing a weatherproof subterranean playground for the Finnish capital’s residents and visitors. Yet hidden behind the bright lights of the underground attractions—which include a museum, church, go-kart track, hockey rink, and more—are emergency shelters fitted with life-sustaining equipment: an air fiation system, an estimated two-week supply of food and water, and cots and other comforts. The shelters reflect a chilling geopolitical reality for a small country that shares an 833-mile border with Russia, its longtime nemesis.

Thought to be the world’s only city with an underground master plan, Helsinki began excavating tunnels through bedrock in the 1960s to house power lines, sewers and other utilities. City planners quickly realized that the space could also be home to retail, cultural, and sporting attractions—and that it could shelter the city’s population of 630,000 in the event of another invasion from the East. The building of the tunnels expanded with new purpose.

Tomi Rask, a preparedness instructor for the city of Helsinki’s rescue department, says the alternative purpose of the tunnels is to “save people against the actions of war.” No Finnish government official would ever mention Russia as the reason for such defensive preparations, but they don’t have to.

“You can plan and prepare without having to point out who explicitly your challengers or adversaries are, because it’s clear to everyone,” says Charly Salonius-Pasternak, chief researcher for the Finnish Institute of International Affairs. “Finland points out who its friends are, Sweden, the U.S., and so on, but there’s no point in pointing out who the adversary could be because there’s only one and everyone knows who it is.”

Growing up in Helsinki during the late Cold War era, Salonius-Pasternak enjoyed the tunnels’ convenience, calculating how far he could walk underground between stores without putting on his winter clothes. Today, Salonius-Pasternak specializes in the country’s security and defense policies, including peacekeeping and crisis management.

Salonius-Pasternak says Finland’s history with Russia is long and complicated. The Russian Empire took Finland from Sweden in 1809 as a result of the Finnish War and operated it for a little more than a century as the autonomous Grand Duchy. When the Soviet Union was formed out of revolution, Finns declared independence in 1917. The following year, after a brief but bloody civil war, the Soviet-aligned Red faction lost to the White faction, which vowed to remain free and Western.

Then came World War II, when the Soviets twice invaded Finland, ostensibly to take enough land to form a protective buffer around Leningrad, modern-day St. Petersburg. Twice the greatly outnumbered Finnish army repelled the Soviets, but both times Finland was forced to sign peace treaties that resulted in a loss of territory along its eastern border.

During the Cold War, Helsinki stood at the crossroads of the East and West, one of the last major outposts separating the NATO and Warsaw Pact superpowers. In recent times, Russian President Vladimir Putin has warned Finland more than once against joining NATO, an uneasy reminder of past tensions.

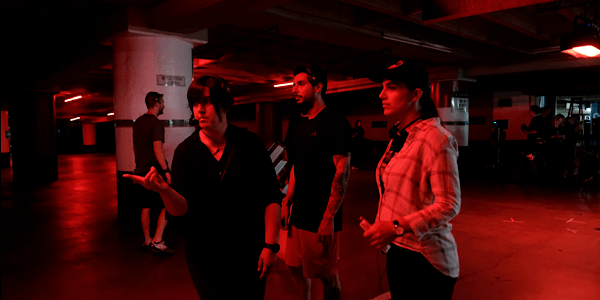

Yet on a typical winter day, when the city receives only a handful of daylight hours, Helsinki’s underground master plan becomes manifest as a way to navigate the city, guiding residents and tourists along bright, colorful passageways lined with markets and shops, to metro stations and the central railway station, while providing shelter from the elements.

“It’s comfortable and safe,” says Eija Kivilaakso, Helsinki’s chief underground planner. “If it’s raining, you can drive into the city center to an underground car park and go straight into department stores from elevators. You can dress for comfort instead of in cold-weather clothes. If the weather is not comfortable, people choose the underground.”

One of the underground’s shining stars is Temppeliaukio, a church carved into solid bedrock. Completed in 1969, its stunning features and superb acoustics have made it one of Finland’s most popular architectural attractions, drawing more than 850,000 visitors a year.

A more recent addition is the privately built Amos Rex art museum, which earned acclaim by the BBC as one of Europe’s most innovative architectural spaces when it opened in 2018. Its 23,500-square-foot exhibition hall, largely featuring modernist works, was built completely underground because the adjoining building, housing its offices and a movie theater, is protected from expansion. The museum was an immediate hit, with long lines and sold-out exhibitions before the coronavirus pandemic.

“When the Amos Rex was [built], that became a very good thing for our underground master plan,” says Kivilaakso. “We saw that it was possible to have more private facilities down there, which gives us more space above ground. It lets us know we don’t have to build large stores or electricity stations or car parks on the ground. We have them underground.”

Whether offering cultural enrichment through art or the simple convenience of getting groceries before heading home on the subway, Helsinki’s underground seems far removed from the doomsday scenarios the bustling tunnels have been readied to face.

“The average Finn spends very little time thinking about Russia, never mind being afraid of Russia,” Salonius-Pasternak says. “Most people don’t think of it in terms of ‘now I’m going into the metro and let me notice all these things that are built in here because it needs to be a functioning bomb shelter, as opposed to just a functioning metro station.’ “