Across the Nation, a Native American Coffee Movement Is Brewing

In a northeastern neighborhood of Portland, Oregon, a small coffeehouse stands covered with pictures of bison. For centuries here, on the land of the Cowlitz, Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, and Clackamas peoples, there have been no bison. But Bison Coffeehouse still pays tribute to the animal that sustained Native American communities across the country. Inside, Native American art adorns the space, centered around a mounted buffalo head.

While the cafe’s decor honors the bison, the business itself is dedicated to a non-Native plant: coffee. And not just any coffee, but coffee roasted by Native American-owned companies.

Portland is one of the U.S.’s foremost coffee cities, but Bison is the city’s only Native-owned coffeehouse. Its owner, Loretta Guzman, is a citizen of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes. In 2014, Guzman opened the coffeehouse with the intention to serve and promote coffee from Native American roasters. In recent years, she’s had more and more companies to choose from, with roasters now opening on reservations from Oregon to Oklahoma.

Coffee has long been an international product. First carried by merchants out of Ethiopia in the 15th century, coffee later became a lucrative crop on Central and South American plantations, tying it inextricably to the colonization of the Americas. While there are some active coffee farms in Hawai’i and California, the plant generally doesn’t flourish in North America. Guzman sells coffee roasted on reservations in Nevada, Arizona and New York, while the companies themselves mostly source their raw coffee cherries from Central and South America.

The far-flung trading of a caffeine-filled drink has a long history in the Americas. Long before coffee was a common beverage anywhere, Native Americans in southeastern North America grew and widely traded yaupon holly, which was brewed as a caffeinated tea. Such teas are used medicinally and as a refreshment by Indigenous peoples. Today, while the yaupon tea industry is still in its infancy, coffee is a culturally and economically significant beverage in Native American communities. That’s according to Priscilla Settee, a member of Cumberland House Swampy Cree First Nations and a professor of Indigenous Studies at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada.

Settee, who recently published a book on Indigenous food systems, says that coffee, though non-Native, is a useful means of economic development for Native American communities. Settee also notes that coffee doesn’t just serve the ‘colonizer’. “I think we have to back up and say, who’s consuming the coffee?” says Settee. “We all love coffee, so why not use that as an angle for keeping the money in the community?”

Guzman agrees. “Native people love coffee,” she says, adding that her Native customers usually order the darkest roast. And, with high unemployment rates on reservations, she hopes the money she spends at reservation-based roasters will go towards more hiring and stronger local economies.

But it wasn’t love of coffee or community feeling that led Guzman to start her business in 2014. Instead, Bison Coffeehouse was inspired by a dream she had during a distressing time in her life.

In 2008, Guzman was diagnosed with stage four cancer. At the time, she was studying to be a dental technician and didn’t qualify for health insurance. She decided to move back to Fort Hall Indian Reservation in Idaho, where her mother was from, for treatment.

One night, during her bout with the disease, she had an unforgettable dream. In it, she saw a bison roaming outside of her father’s home back in Portland. “What is a bison doing in the city?” Guzman recalls thinking. The next morning, both her mother and her grandfather assured her that the dream meant that she would be healed.

In 2009, Guzman recovered and returned to Portland. She finished dental school, but following the 2008 financial crisis, it was hard to find work. Still pondering the meaning of the bison in her dream, she hit on the idea of a coffeehouse named in its honor. Luckily, her father owned a vacant Portland building that was just the right size for a cafe. She soon began studying coffee and reaching out to coffee-roasting companies across the country.

Guzman was determined to work mainly with Native-owned coffee roasters, particularly those with businesses on tribal land. “I lived on a reservation, off and on my whole life,” Guzman says. “We do our hustles.” It wasn’t long before she met Amy Wallace, a member of the Unkechaug Indian Nation and roast master at her family’s business, Native Coffee Traders of Mastic, New York.

On the Poospatuck Indian Reservation, the company roasts organic, fair trade-certified Arabica coffee beans grown by Indigenous farmers in Central and South America. The company got its start when Wallace’s uncle, Harry Wallace, set out to find a way to increase the revenue of the reservation. In 1994, he launched Native Coffee Traders.

27 years later, Wallace says that more and more Native-owned coffee businesses are opening by the day. But the coffee-roasting business isn’t an easy one, she cautions. “It’s still a hard process and it’s still difficult to get into the market,” says Wallace, noting that her and her uncle’s main hurdle has been competing with large coffee companies with considerably more money for advertising and marketing. However, there’s strong solidarity in the Indigenous community when it comes to coffee. Wallace says that 80 percent of her wholesale beans are purchased by other Native American-run businesses.

After Guzman and Wallace hit it off, together they mixed up Bison’s house blend. The light roast that Guzman offers, from the local Coava Coffee Roasters, the only coffee at the shop that doesn’t come from a Native-owned brand. Nevada’s Star Village Coffee, based on the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, provides the medium roast, while Wallace also provides the dark. Guzman strives to serve different roasts from each company she features, to minimize competition, she explains.

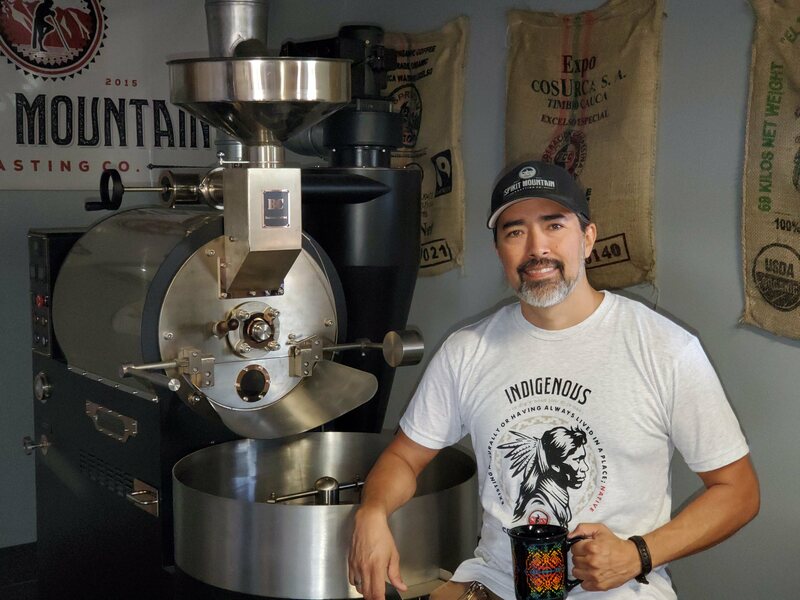

Yet when the Yuma, Arizona-based Spirit Mountain Coffee Roasting Co. got in touch, Bison Coffeehouse already had a light, medium, and dark roast. To include them, the company and Guzman created the dark-roast MMIP blend, in the hopes of bringing awareness to the ongoing crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples.

Walking into Bison Coffeehouse, a customer just looking for a cup of black coffee or a latte might not know that they’re supporting Native-owned businesses across the continent, but Guzman is passionate about promoting the companies behind her varied roasts. “I really push my Native roasters, because those are my people,” says Guzman. “We might not be the same tribe, but they’re still my people.”