The Lost Language of Easter Island

On the outskirts of Hanga Roa, Easter Island’s only town, the Museo Rapa Nui has a small but striking collection. It includes a rare female version of the monolithic statues known as moai, and sets of piercing moai eyes made from white coral and red volcanic rock. Finely worked obsidian tools sit alongside displays on the Birdman contest, which involved swimming through shark-infested waters and searching an offshore islet for a seabird egg in order to claim the spiritual leadership of Easter Island. With so much to see, it’s easy to overlook the carved wooden fish in a glass cabinet. Raised on a stand, as if held aloft by a proud angler, it is the color of dark chocolate and roughly the size and shape of an oar blade. The design may be relatively simple, but this object represents a great—and unsolved—linguistic puzzle.

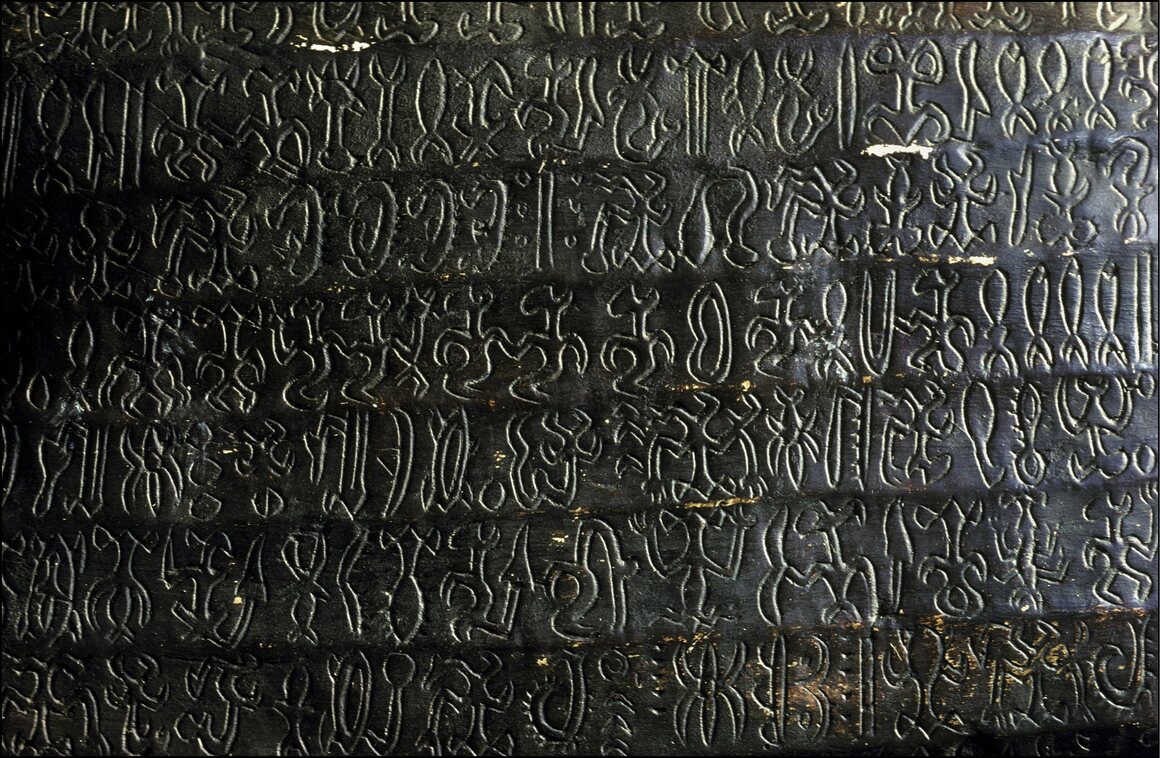

The fish is covered with rows of stylized glyphs. Some resemble human forms and animals and plants, while others are more abstract—circles, crosses, chevrons, lozenges. This is rongorongo, the only indigenous writing system to develop in Oceania before the 20th century and, according to James Grant-Peterkin, author of A Companion to Easter Island, one of “the last remaining mysteries on Easter Island.”

Known locally by its Polynesian name Rapa Nui, Easter Island is the remotest inhabited island on Earth, 1,298 miles from its nearest populated neighbor. According to oral traditions, rongorongo tablets were brought here by the first settlers, who arrived between the years 800 and 1200, probably from the Marquesas or Gambier islands, which are now part of French Polynesia. Academics disagree about when the writing system emerged. Some believe it long predated European contact—which began when Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen reached the island on Easter Sunday 1722—while others argue that it emerged as late as the 1770s, after the Rapanui people saw European writing for the first time during a Spanish expedition to the island.

It appears that rongorongo was primarily used for religious purposes and only understood by the local elites. “Rongorongo was never a script of the common people,” says Cristián Moreno Pakarati, head of research at the Rapanui Pioneers Society. “Only a handful of wise literate people, according to tradition only men, could interpret the texts.” Knowledge of the script began to disappear in the 19th century, he adds. “The Rapanui population faced the disintegrating forces of the West in the form of disease epidemics, piracy, ‘blackbirding’ slave raids [in which up to 1,500 islanders were kidnapped and forced to work in Peru] and religious indoctrination.” As the Rapanui population declined by approximately 95 percent—a census in 1877 recorded just 111 Rapanui islanders—only a fragmentary understanding of rongorongo survived.

But the knowledge was never completely lost, says Steven Roger Fischer, former director of the Institute of Polynesian Languages and Literatures in Auckland, New Zealand, and author of Island at the End of the World, A History of Writing, and A History of Reading. “Several Rapanui still remembered the traditions, some chants and customs, and relayed a few of these things to foreign visitors well into the first two decades of the 20th century.”

Some of these visitors took notes on what they heard about rongorongo, and over the years, there have been various attempts to decipher the script, but it has proved a difficult task. One problem is the lack of data. Only 26 rongorongo objects have survived—the Museo Rapa Nui’s is a replica, and the originals are all overseas, predominantly in Europe, the United States, and mainland Chile. Some have only a few lines of text. “Some rock carvings on the island [have individual symbols that] are very similar to rongorongo, but there isn’t a line of text anywhere,” says Grant-Peterkin.

Fischer believes he made a major breakthrough in the 1990s by working out the key to the script’s structure. He says most surviving examples of rongorongo appear to be “cosmogonies”—stories about the creation of the universe and the natural world—that reproduce “an ancient East Polynesian oral tradition, which the first settlers would have brought with them.” Based on years of research, detailed in his book Rongorongo: The Easter Island Script, Fischer argues that the language’s similarities with Western writing are few—mainly just the linearity and left-to-right reading direction. “It’s a logographic or word-writing script, in that each glyph or sign [represents] an object whose name is to be spoken aloud. However, these glyphs are merely nominal prompts, leaving the chanting reader to fill in, from memory, a good deal of unwritten text.”

Despite the work of the likes of Fischer—whose claim to have deciphered rongorongo has been challenged by other linguists, who argue there are problems with the structural pattern that underlies his theory—we remain a long way from being able to read long passages of rongorongo. Pakarati says there haven’t been any major steps forward in recent years, largely because of the small number of rongorongo tablets in existence. Only limited information was gathered in the early 20th century from Rapanui people who retained knowledge of the script, and most symbols still cannot be identified. But there are hopes machine learning could help in the future. In October 2020, for example, researchers at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory announced they had developed an algorithm that could “automatically decipher a lost language, without needing advanced knowledge of its relation to other languages,” according to a release. Although the researchers didn’t look at rongorongo, their work could potentially help to improve our understanding of the script.

Pakarati, who highlights the importance of including Rapanui people in efforts to decipher the tablets, isn’t optimistic that rongorongo will ever be fully understood. Nevertheless, the script still generates significant pride on the island, as well as intrigue. “It is a source of great admiration and awe towards our ancestors,” he says. “But on the other hand, [it is] as much a mystery as for the rest of the world.”