To Save Norway’s Stave Churches, Conservators Had to Relearn a Lost Art

To step into one of Scandinavia’s surviving stave churches is to enter the past. Shadows shift and tell stories in the elaborate carvings of intertwined beasts that are hallmarks of the churches’ unique architecture. Sounds reverberate off the timber as if traveling across centuries. The air feels dense with the tang of hewn wood, peat smoke, and pine tar.

As early as the 11th century, builders began erecting these churches all over the region. Much of Europe was raising massive cathedrals of stone during this period, but the Scandinavians knew wood best. While each house of worship was unique, all of them had staves, or load-bearing corner posts joined to vertical wall planks with a tongue-and-groove method.

Archaeologists believe there were once nearly 2,000 stave churches, or stavkirker. Today, fewer than 30 remain, mostly in western Norway. As the number of churches dwindled, so did knowledge of the complex ancient technology needed to maintain them. To preserve the surviving churches, researchers and conservators have had to piece together a lost craft through interviews, rediscovered documents, and mass spectrometers that discern the chemical composition of the churches’ ancient weatherproofing.

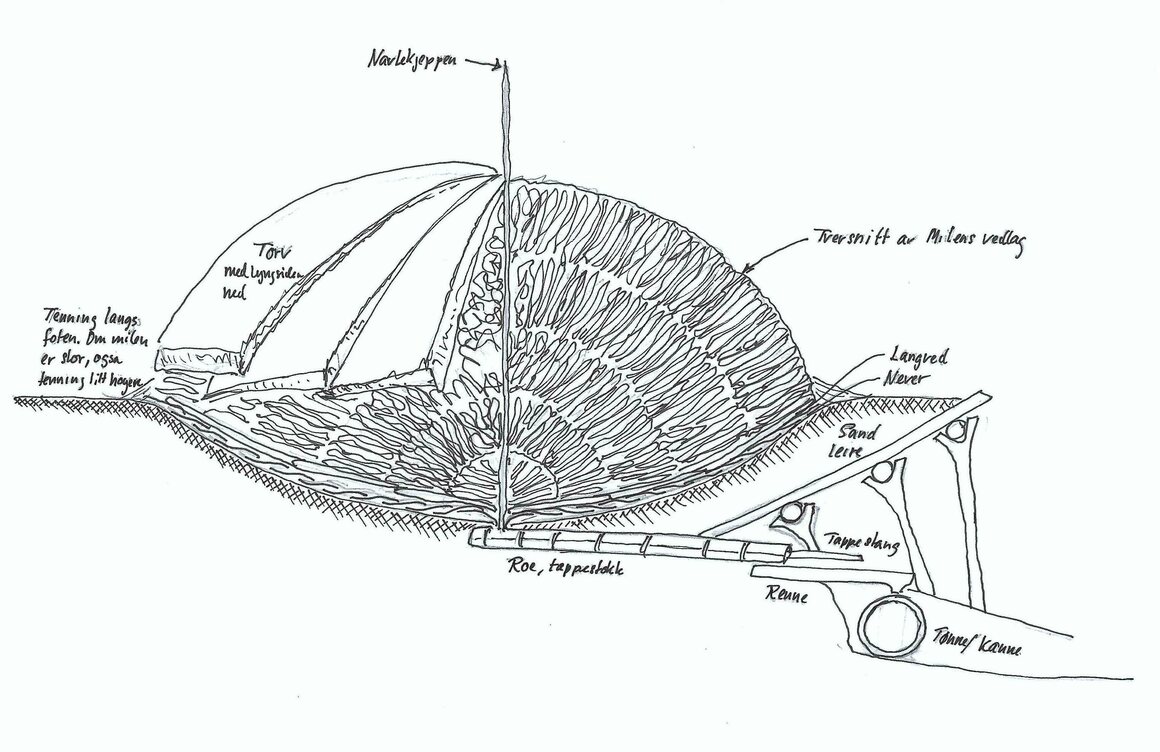

As they did with the ships that carried them as far as Africa and North America, the Nordic builders coated their stave churches with tar to seal and protect the wood from frigid winters, long days of summer sun, and Scandinavia’s full spectrum of precipitation. The special glaze, made from pine resin, took days to prepare in a massive peat-and-wood mound that Ole Jørgen Schreiner, a traditional tar expert, calls a mile. Creating one was a “complex and laborious project” in and of itself.

“The actual construction of the mile takes one to two days, and the burn itself takes (up to) three days,” says Schreiner, via email. He oversees the maintenance and repair of the Norwegian Folk Museum’s historic buildings in Oslo, and has created the ancient style of kiln for demonstrations. “Just building it requires accuracy … It’s not just sticks thrown in a pile, but precisely stacked and knocked together to avoid air pockets that can cause problems during the burn.”

The stacked wood would have been arranged on a hillside, and insulated with at least a double layer of cut peat. Tenders needed to keep a fire around the mound burning at the right temperature, and add more peat when needed. Over days, the indirect heat reduced the wood at the center of the kiln into charcoal and released the tar, which was then collected via a drain system downhill, which also had to be closely watched. The labor-intensive, time-consuming medieval method was eventually all but forgotten, replaced by faster, easier industrial methods.

“Tarring with pine tar is among the oldest surface treatments known in Norway and elsewhere in the Nordic countries,” says Inger Marie Egenberg, who heads the University of Stavanger’s conservation archaeology department. But “the knowledge was not at all handed down through generations. Some knowledge, however scarce, remained among builders of traditional wooden boats.”

Some tidbits also survived as scraps of folk wisdom. Schreiner notes that a document from the 1940s claims that the best tar was made at midsummer, adding: “There may be something to it: Around midsummer there is quiet and often stable weather, and it’s ideal for mile burning.”

Reconstructing how the traditional stave church tar was made and applied is vital for the churches’ survival in Norway. The nation’s cultural heritage laws require that historic buildings be maintained and repaired using traditional materials and methods, which means no industrial kilns or modern wood protectants. But when Egenberg began her research into traditional tar production in the 1990s, she found that the tar being used to maintain churches performed poorly and had to be reapplied annually, rather than the traditional three to five years. She pored over handwritten church records from the 17th and 18th centuries for clues to the lost tar production process, and then turned to a modern lab to test and relearn the ancient craft.

Analyzing the chemistry of different samples of ancient tar, Egenberg found that, while made from the same raw material, they differed in texture and viscosity—“one [was] quite light and transparent like a golden syrup, one is dark, thick, and mushy”—based in part on their intended application. South-facing facades and roofs, for example, were more exposed to sunlight and required thicker, more protective tar.

Egenberg’s experiments also revealed the tar had to be heated to about 140 degrees Fahrenheit before being applied in multiple layers to create a lasting protective coat. While her landmark research over the last 20 years has improved the quality of traditional tar production and application, the craft remains in jeopardy. Egenberg says the last of the skilled craftsmen, mostly old men, typically made small batches on the side to earn extra income. As their numbers have shrunk, so has production. “After 2010 or so, the supply decreased,” she says. “Now it is a huge problem.”

Christina Ljosåk Ross of Norway’s National Trust agrees: “Lack of production of tar is a big challenge.” She estimates that fewer than half a dozen traditional pine tar producers remain in the country, producing batches of a few gallons rather than the hundreds of gallons a stave church might require for a single application.

Recently, the Nordic Tar Network, which Schreiner advises, has begun offering courses and demonstrations of traditional tar production to boost interest in, and knowledge of, the fading craft. Schreiner says producers are now also working with road construction crews to salvage stumps—the most resinous parts of the tree—that would be discarded as waste. They make great material for miles, says Schreiner.

Not every stave church caretaker faces such challenges—at least outside of Norway. Brian Kringen and his wife, Joyce Kringen, serve as codirectors of Chapel in the Hills in Rapid City, South Dakota, one of a half-dozen or so stave churches in North America, built in the 20th century by descendants of Scandinavian immigrants. The church the Kringens manage is a replica of Norway’s Borgund stave church and, while Kringen is familiar with the laborious task of maintaining a protective coat on its multitude of levels and layers and nooks and crannies, he smiles with relief over not cooking down pine resin for days. “We use a product called Woodguard,” says Kringen. “We buy it retail over the internet.”

On Washington Island, where the northeast tip of Wisconsin juts into Lake Michigan, Richard Purinton has been a volunteer caretaker and woodcarver for his local stave church since its construction in the 1990s. Purinton, who wrote the book Island Stavkirke in 2017, also uses Woodguard, mixed with a tint that best mimics the dark wood of the Scandinavian churches—the tint’s name happens to be “pine tar.” Purinton says spraying the commercial product on every six years or so has been easy and effective: “But then, we’re only into our third decade since construction, a youngster in terms of stavkirke history.”

The allure of Woodguard is not lost on Egenberg and other Norwegian conservators—but neither is their responsibility, even if the government didn’t require traditional methods be used. “We know that, from a purely technical perspective, modern materials probably would prove superior. But then the stave churches would lose their authentic appearance and smoky smell,” Egenberg says. “That is basically what conservation is about, preserving both the material content and the cultural, historical information that the property is a bearer of.”