The Grand Canyon’s Caves Are Full of Sloth Dung and Mummified Bats

Many of the millions of visitors snapping selfies on the Grand Canyon’s rim have no idea that the ruddy limestone cliffs are pockmarked with caves. “There’s really more caves in the Grand Canyon National Park than any other place,” says Jim Mead, a paleontologist and director of The Mammoth Site in South Dakota. Carlsbad Caverns, for instance, boasts somewhere around 119, while the Grand Canyon probably houses hundreds. The network within the steep walls is filled with the remains of plants and animals—hidden reminders of the region’s cooler past.

For tens of thousands of years, these hard-to-reach crannies have provided the perfect home for wood rats, bats, birds, and now-extinct mountain goats and sloths. The caves vary in size: Some are so narrow you can only enter on all fours, while others are roomy enough to spin in without touching the walls. The bone-dry conditions create an ideal preservation environment, allowing researchers to peer back into over 40,000 years of history and get a sense of a world that existed when much of North America was covered in a thick sheet of ice.

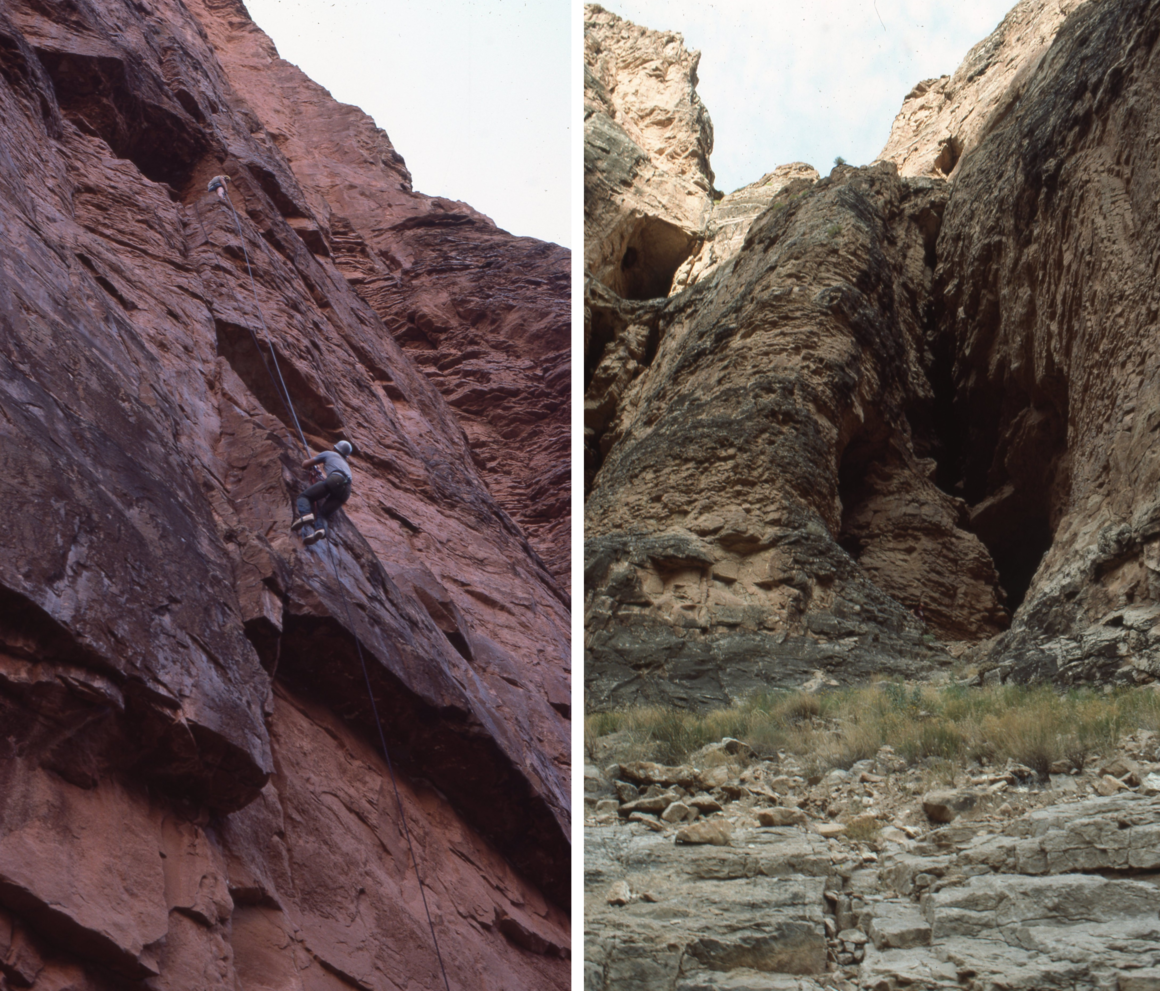

Some are a scramble away from the rushing Colorado River; others are hundreds of feet off the ground. Ancient humans found their way to some of these hard-to-reach caves, too: split-twig figurines were probably left inside around 4,000 years ago. But contemporary scientists didn’t venture in until the 20th century.

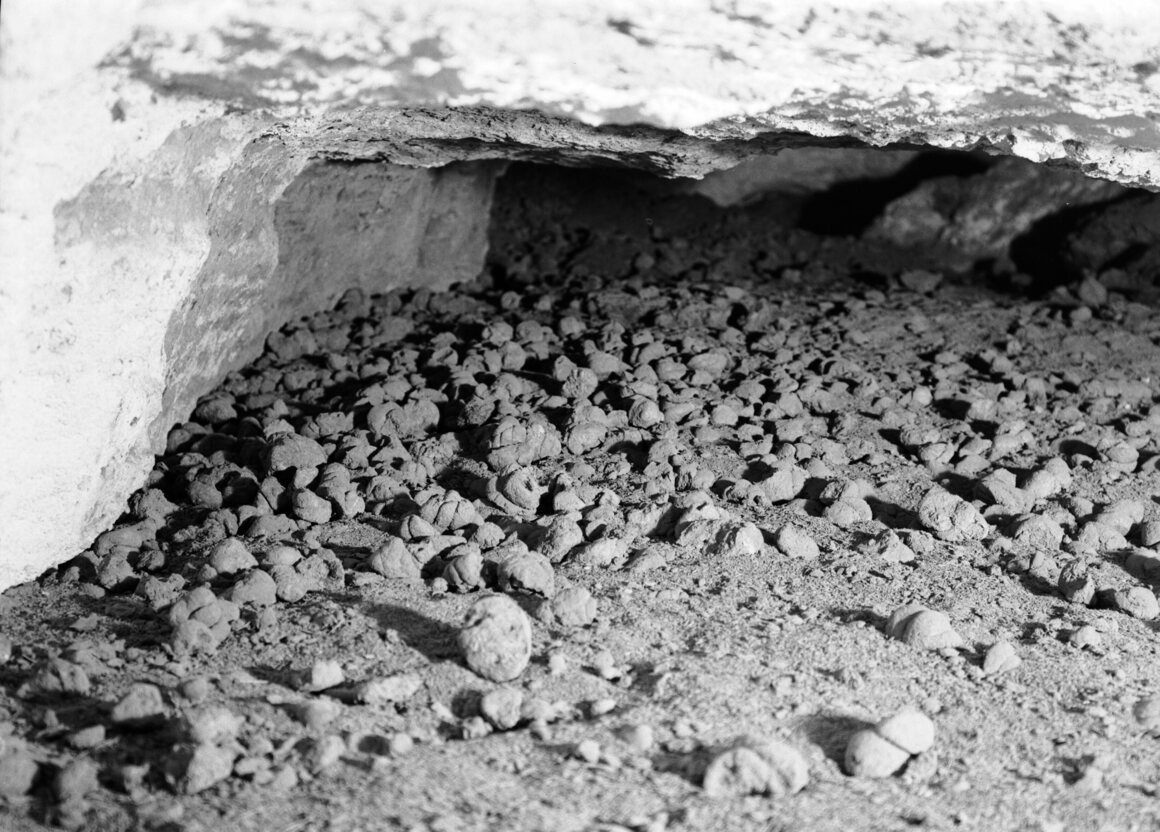

They began with Rampart Cave, in the far western end of the Grand Canyon. There, they encountered hundreds of dung balls scattered on the floor. To the undiscerning eye, these appeared to have been excreted fairly recently—except that this was the 1930s, and the droppings belonged to the 500-pound Shasta ground sloth, extinct for over 10,000 years. (Mead says when he saw the inside of the cave decades later, “it looked like a barnyard,” but with a more mellow smell.) Members of the Civilian Conservation Corps, a Great Depression-era men’s work relief program, dug test excavation pits in the cave in 1936, and over subsequent decades, work also revealed remains of reptiles, bighorn sheep, and extinct goats and horses. Based on radiocarbon dating, the sloth dung deposits seem to be between about 40,000 and 11,000 years old.

Mead’s interest sparked in 1969, during a rafting trip through the canyon’s Colorado River with Ice Age extinction expert Paul S. Martin. Mead went on to do his doctorate with Martin at the University of Arizona, where he studied these time capsules from the Pleistocene.

When Mead first visited the canyon in 1969, scientists had thoroughly combed only two caves along the 270-mile stretch of river. Even so, finding a wood rat midden or the skull of an extinct mountain goat in a cave within the canyon’s 340-million-year-old marine limestone wasn’t unexpected. “The surprise was not finding something—the surprise was not to find something,” says Mead, the lead author of a paper detailing what scientists have learned in nearly a century of cave excavations in the park that will be published in a forthcoming volume of Geology of the Intermountain West.

While the caves in the park are not open to the public—and most locations are kept secret, to protect them—Rampart Cave “was on Arizona highway maps for a while,” says Mead. Intruders set a long-smoldering fire in 1976 that burned well into the following year. In an interview with The New York Times in 1977 about the destruction, Paul S. Martin likened the fire in this cave to one in a “major wing of a natural history museum.”

The hundreds of other caves have given Mead and his colleagues more than a career’s worth of work. The tasks are arduous—and sometimes, it takes a lot of effort just to arrive at a site. While some caves, such as Rampart, can be reached on foot from the river, many require “ropes and life insurance,” Mead says, because they’re located in sheer cliff-faces. He and colleagues have generally worked along the river—in the 1980s, they took a 40-day rafting trip, working in caves on the way—but they’ve also used helicopters to reach more remote parts of the canyon that are difficult to hike to.

Mead says there are still more than 150 miles of river corridor that researchers have yet to study. One cave is so remote that researchers only found it in 2008—and its 40 miles of passage make it one of the longest caves in the world. It’s also the final resting place of hundreds of desiccated, mummified bats. Despite being thousands of years old, they appear to simply be sleeping among the gypsum crystals.

The caves contain mummified birds, as well: “Some condors and their tissues are so well preserved…we get skin and everything preserved on some of these bones,” says Steve Emslie, professor of biology at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. Emslie has explored the caves with Mead, and is an expert on the birds that lived in the region during the Ice Age. He has been able to chemically analyze the desiccated tissue remains of the condors to show that the Grand Canyon condors were likely feeding on megafauna that went extinct, which in turn led to the demise of the birds, too.

Scientists can also glean a lot from the animals’ poop. The shape may point to a specific species: A “bowling ball” shape suggests an extinct mammoth, Mead says, while a “Hershey’s kiss” indicates the work of an extinct shrub ox. Microscopic remains can also be telling. By studying ancient DNA in the sediment within the caves—a mingling of dirt, hair, plant remains, and dander—scientists can learn about the fauna and flora that flourished tens of thousands of years ago, when there were pine trees “right on down to the river,” Mead says. (“When you hike through the canyon today down low, you kind of go, ‘I would give anything for some shade,’” he adds. “During the Ice Age, this is not an issue—you got shade all over.”)

Old plant matter in the poop helps scientists decipher animals’ eating habits. Pollen, which drifted through the air and was consumed by animals, also holds hints about the regional plant community. Wood rat middens, too, are useful records of plants and animal remains left stacked in neat piles, undisturbed for thousands of years.

Mead isn’t exploring the caves much these days. It’s complicated to navigate permitting for work in the park, and then taxing to get to sites even with the go-ahead. Fossils previously collected in the caves are in the Grand Canyon Museum Collection, so researchers can still access them—but Mead champions future fieldwork, too. “I’m getting old,” Mead says. “I don’t wanna, you know, go screaming over the edge of a cliff on a rope anymore. But there’s still a lot to be done. It just needs the right person just to go out there and say ‘Yeah, let’s look at everything.’”