“I Have Never Seen Power Like This Before.” Interview With Shalini Kantayya, Director Of Big Tech Doc, CODED BIAS

When it comes to the carryover effect between America’s social dilemmas and its dependence on artificial intelligence, the command, unfortunately, is not “delete,” it’s “copy and paste.”

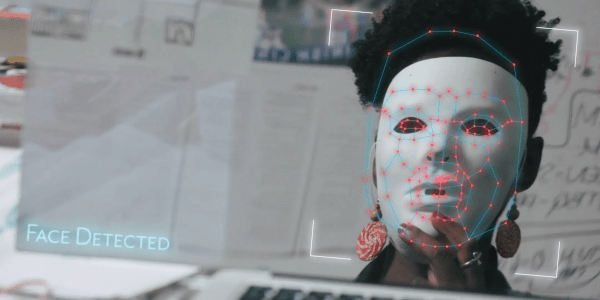

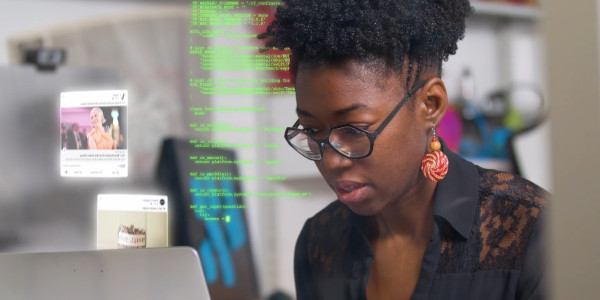

That is the basis of Shalini Kantayya‘s frightening and informative documentary Coded Bias. The film, which premiered at Sundance 2020, has been the source of much-needed attention and much-deserved praise. It revolves around the subject and consequences of mass data collection through the eyes of international researchers, activists, and analysts – including Joy Buolamwini, Cathy O’Neil, Amy Webb, Silkie Carlo, and Zeynep Tüfekçi. Together, a portrait comes together that severely challenges the merit of algorithms and the trust that our society has in them.

Kantayya spoke with Film Inquiry in anticipation of her film’s release on Netflix (streaming now). In conversation, the director addressed the limitations of algorithms, the need for data regulation in America, and the international response – or the lack thereof – to these issues.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Luke Parker for Film Inquiry: An important point the film makes is that these computers aren’t making moral, conscious decisions – they’re making mathematical predictions. With our data profiles out there evolving every day, are humans becoming too predictable? Is actual free choice something that we are losing?

Shalini Kantayya: This stuff is always talked about in terms of privacy, and I think the more accurate term is “invasive surveillance.” I didn’t actually realize until making this film the ways in which our data is brokered between companies to create, almost, a complete psychological profile of us and market to us by name based on our likes, our dislikes, and our past behaviors.

Yes, I think that we have not explored this invisible hand of AI on our free choice. I grew up in an era where the DJ chose the next song, it wasn’t Spotify saying, “would you like to listen to this?” Or Netflix saying, “do you want to watch this movie next?” I relied on cultural curators for my content. And now, we haven’t begun to think about what it means when we have an ad that follows us from platform to platform, and what that invisible man, that silent nudge does to human behavior.

I think it’s frightening. And I do think that we are in that moment where we’re starting to grapple with whether we have free choice.

You were mentioning the surveillance side of this, and a lot of terms get thrown around in this film; scary things like “mass surveillance state,” and “corporate surveillance.” How much of that did you know going into this project, or was this something that you heard and went like, “oh, crap!”

Shalini Kantayya: [laughs] The latter. Three years ago, I didn’t even know what an algorithm was. My entire credential to making this film was being a science fiction fanatic, which didn’t really prepare me for the realities of making this film.

And no, I did not realize the ways in which a complete psychological profile can be built based on our data with a high level of confidence. And like Zeynep Tüfekçi says so poignantly in the film, it can predict, with a certain amount of confidence, really intimate things about your behavior and market to you at the time you’re most vulnerable to that behavior. She gives the example, that I think is so astute, of a compulsive gambler being shown discount tickets to Vegas.

So no, I stumbled down the rabbit hole and kind of fell deeply down. And in some ways, I’m still in the rabbit hole. [laughs] Because Coded Bias is just the beginning of the conversation.

Because they’re based in math, these algorithms are often seen as objective truth. And that’s part of the reason why organizations support and rely on these systems. I agree. I think your film is a great start to this question, but how do we shift this perception of algorithms to reflect the issues that they present?

Shalini Kantayya: Well, I think that we don’t even have basic literacy around algorithms, machine learning, AI. Even someone like me who reads Wired religiously and loves the tech space, I was completely unprepared for the discoveries I made.

I was just on a panel with Cathy O’Neil, who said, “it’s data science, so let’s treat it like science. Let’s not treat it like a faith-based religion.” I think what’s happening here is that the public, including myself, mostly doesn’t understand how this works. It wasn’t until I spent two years with the brilliant and badass cast of Coded Bias that I could start to discern what is sound science and what kinds of systems we should trust, and what is just bogus, bologna, pseudoscience that a company is trying to benefit from.

That is what I would advocate for: just basic literacy. A 10-year-old is going to start using a cell phone in the 5th grade. That’s when we should start teaching about data collections, about how algorithms work.

For instance, there’s a company called HireVue that says it can judge whether a candidate is a good candidate based on their facial expressions on camera. That’s all complete pseudoscience. That’s bogus science. And I wasn’t able to discern that until after making this film. The algorithm that decided Daniel Santos was a bad teacher in my film, the value added model which teachers all across the country are still fighting, including in Florida, was an algorithm that was designed to judge fertility in bowls.

Now that I understand how these algorithms work, I can now ask if an algorithm can judge if a teacher is a good teacher? What are we even saying here? Are we saying that what’s important about a teacher is that they move the test scores from here to here? Is that how we’re judging? Because that’s what that algorithm does.

Some of the algorithms that are being used to judge predictive policing in certain neighborhoods…we have to think about it. I live 20 minutes from Wall Street and I can tell you we don’t have crime data. We have arrest data. The same communities have been penalized and over-policed – we know about those systematic inequalities – and so, when you have an algorithm that’s judging where arrests have taken place, that algorithm is just sending you back to the same neighborhoods that have been over-policed and over-brutalized.

To me, it’s a matter of literary for all of us to be able to lay bare whether it’s fair for these systems to make these decisions. The trust that we’re giving them is insane!

You discuss literacy in the public, but I think one of the most frightening elements of the movie is when it becomes more and more clear that the companies behind this technology don’t entirely understand it. They see the product but don’t understand how they got there. Is it fair to say Frankenstein has lost the leash to his monster?

Shalini Kantayya: Oh, absolutely. There was a moment where I was sitting with Zeynep Tüfekçi and I was like, “wait a minute, you’re telling me the engineers who designed these systems don’t know how the system arrived at that decision?” And she just explained to me that no, they don’t! [laughs]

So we have a system that’s not transparent, that’s sort of a black box, that there’s no way of going back and asking, how did it arrive at this decision? What happens if it makes a mistake? How easy is it to replicate that mistake? What are the consequences of that mistake – like the case we saw in the UK where a 14-year-old child is traumatized by police use of facial recognition. Or you have a probation officer and a judge looking at a risk assessment model, judging someone who’s been a model citizen their whole lives as high risk.

Yes, it is sort of a Frankenstein situation. I don’t think there are enough safeguards in place to protect against these systems that are black boxes and not transparent to us.

Regulation around data is lacking, especially in America. Why is there a delay?

Shalini Kantayya: I’ve never seen power like I’ve seen with big tech. My last film was about renewable energy where I took on the fossil fuel industry; I’m no stranger to speaking truth to power. I have never seen power like this before. And that is because big tech money is in liberal politics; it’s in conservative politics; it’s in the computer science universities that are teaching this stuff.

And the other thing with AI, in particular, is what Amy Webb talks about in the film: there may only ever be 9 companies who control AI, because these nine companies have a 15-year head start on data collection. Right now, we don’t have any laws in place that would break up those companies and that data collection and actually allow for some innovation to happen. That is the other thing. We’re looking at these 9 companies – half of which are in China, half of which are here – that’ve had this running head start. They’re really the ones that have the ubiquitous power on how this technology is developed.

I think we have a stunning lack of imagination about how these systems could work because they’re controlled by a very small group of companies that work off of this surveillance capitalism model of data collection. I don’t think we’ve unleashed the kind of policy that would allow for us to see what AI would look like towards the public goal.

With our dependence on this technology and the rate at which computers learn, this is a problem that’s constantly growing. As we wait for legislation to take hold, what consequences are building up? What harm is being produced the more time we spend waiting?

Shalini Kantayya: I think, certainly, income inequality is the thing that I can point to. In the pandemic, we’ve seen the biggest tech companies – like Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon; Bezos is now on track to be the world’s first trillionaire – grow exponentially while the rest of us are losing. Where women are falling off of a cliff and going back to literally 1985.

You mean financially?

Shalini Kantayya: They’re leaving the workplace in droves because they’ve had to bear the brunt of child care with schools closing. There’s definitely the massiveness of inequality because that has an impact on democracy.

But I think that what’s at stake here is that we’re moving away from democracy and towards a type of technocracy. And that sounds kind of extreme but it’s actually, in a nuts and bolts way, true. That’s because we see that, more and more, our public square is moving from what I would call “the sacred space of the independent cinema hall,” from our community centers, from our town halls to the technology space. We didn’t make the rules there, but we have to abide by them.

To give you an example, if we post something on Facebook and the algorithm hides it to the bottom of the feed – like it did when Senator Elizabeth Warren wanted to regulate Facebook – you have to ask if we have Freedom of Speech? If you go to a public protest and you know that law enforcement is there and can scan your face without any elected officials overseeing that process, representing “we the people,” are you going to go to that protest if you’re on probation? Or if you’re in any kind of vulnerable position? Do we still have the right to assemble, then?

And so, you see the ways in which technology is essentially intersecting with every right and freedom that we enjoy as people of a democracy. We don’t have any rules in place to regulate that conduct. When it comes to Facebook, there are more rules in place that limit and govern my behavior as an independent filmmaker than that actually govern Facebook’s behavior. That can’t be allowed. There are some big holes in Section 230 that need to be closed.

You show a senator at one point who says something along the lines of China being the black sheep that we don’t want to emulate in America. But you follow a subject in China who’s not only okay with the surveillance technology and the facial recognition software, but actually advocates for it. She believes that China’s social credit system and the gear behind it can only help her community. Why was it important for you to broadcast this perspective?

Shalini Kantayya: I think it was important for me to show these different global approaches to data protection. You have Europe that has some regulation that puts data rights in a civil rights and human rights framework. You have the US, the home to these technologies, that’s like the wild, wild West. And then you have China, where an authoritarian regime has unfettered access to your data and combines that with a social credit score that’s not just based on your behavior, but on the behavior of your friends. Cathy O’Neil calls it “algorithmic obedience training.”

I thought it was important to put it in there because the subject is like a skater; she looks kind of counterculture, like a lot of us, and I was just as surprised by what she said as you were when the translation came in.

I think it was important to say because we the people of democracies like to think of that as a galaxy far, far away. But I really think that it’s a black mirror that’s much closer to us than we think. How many times have we judged someone based on how many Instagram followers they have? Or wanting to delete a post because not enough people liked it? It’s reshaping our behavior in ways that we are not seeing. I think that she is so identifiable because there’s a part of us that’s like, “wow, I can buy a candy bar with my face! I can pay for dinner and not carry any cards,” without really thinking about what we’re losing in this race to efficiency.

Your film is timestamped simply because we never see anyone wearing masks. How have these problems progressed during the pandemic?

Shalini Kantayya: Over the last year, our reliance on these technologies have grown exponentially. For example, this (Zoom) is the only way we could do this interview today. It’s the only way we can have this kind of conversation and be together. I don’t know if you read the terms and conditions when you checked in on this Zoom call, but I did not, and you’re a journalist.

These days, we have even fewer opportunities to opt out. There is no way not to participate online. There’s no way that we can opt out of these systems; we are increasingly reliant on them. So, it is more urgent than ever that we pass some basic legislation that would protect our civil and human rights.

Your past films have all, in some way, reflected the downsides of technology. That may be a bit of a simplification, but at this point, after all of the research and work that you’ve done, do you see any positives about technology or its potential? Or do the actions of the companies in control counteract and cancel those benefits in your mind?

Shalini Kantayya: Well, I love technology. My debut feature, Catching the Sun, was about small-scale solar and how it can uplift the lives of working people. So, that was a much more utopian take on disruptive technology.

I definitely love disruptive technology. I hate authoritarian uses of technology. And I think that’s what we have here. Your child should not have to choose between going to math class and a company having their biometric data for the rest of their lives.

Cathy O’Neil uses the metaphor of calling for an FDA for algorithms. I just got my first doze of the Pfizer vaccine, and I was so grateful to scientists. People who were skeptical asked me if I trusted the vaccine, and I said absolutely, because I trust the American CDC and I trust the FDA. And we need an FDA for algorithms. That does not mean I don’t like food, or I don’t like drugs, it means that I believe in a certain standard of health and safety for these technologies. That’s what I’m advocating for.

Film Inquiry would like to thank Shalini Kantayya for taking the time to speak with us!

Coded Bias is available to stream now on Netflix.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Join now!