How to Recreate 1,300-Year-Old Cookies

If cookies go a few weeks without getting eaten, they turn weirdly soft or dissolve into fine dust. If cookies go 1,300 years without getting eaten, they get carefully preserved in a case at the British Museum.

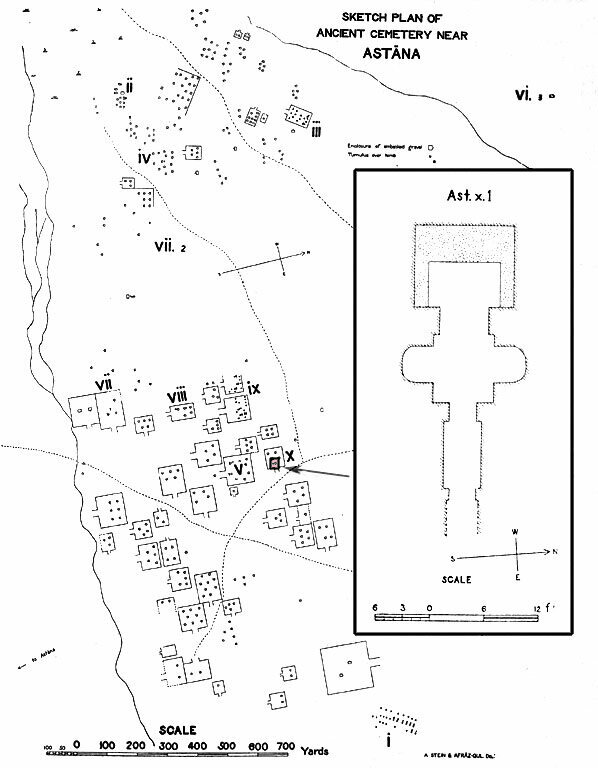

In the winter of 1915, the British-Hungarian archeologist Marc Aurel Stein opened a tomb in Xinjiang. Known as the Astana cemetery, these gravesites were where residents of the nearby oasis city of Gaochang buried their dead, roughly between the 3rd and 9th centuries. As the membrane between Central Asia and China, and the path to the Middle East, Xinjiang has been fought over for centuries (a fight that continues today, as China uses an iron fist to control it as an autonomous province). Gaochang, meanwhile, lies in ruins. But the Astana cemetery, with more than a thousand tombs preserved in the dry heat of the Turpan Basin, tells the story of the once-prosperous ancient city.

The Astana cemetery shows how Gaochang was once a prominent stop on the Silk Road, especially for Sogdians, a people from Eastern Iran who often traveled across Eurasia as merchants. Opening the tombs, Stein found heaps of evidence pointing to Gaochang’s role as a place of “trade exchange between West Asia and China.” Though the vast majority of the dead at Astana were Han Chinese, Stein saw corpses with Byzantine coins in their mouths and Persian textiles included as grave goods.

But inside one tomb, Stein found neither of these things. Grave robbers had emptied it of everything, “except [for] a large number of remarkably preserved fancy pastry scattered over the platform meant to accommodate the coffin with the dead,” he recalled later. Stein was taken aback by the beauty of the cookies and their wide variety of shapes—flat wafers with elaborate designs, delicate, lace-like cookies, and “flower-shaped tartlets . . . with neatly made petal borders, some retaining traces of jam or some similar substance placed in the [center].” In the arid earth of the cemetery, the sweets managed to survive to modern day.

Today, the pastries are owned by the British Museum, as part of what Stein described as his “haul” of artifacts sent back to the United Kingdom. During his expeditions, Stein also helped himself to priceless cultural objects, such as the first-known printed book. Stein’s plundering of the Diamond Sutra caused vociferous protests in China. In 1961, the National Library of China released a statement saying that Stein’s book theft was enough to cause “people to gnash their teeth in bitter hatred.” The cookies, in comparison, are regarded more as curiosities. A 1925 article in The Times of Mumbai, describing an exhibition of Aurel Stein’s finds in New Delhi, noted how “the most remarkable of all the objects are the actual pastries deposited with the dead as food objects,” with the author writing that they closely resembled “the ‘fancies’ of a modern confectioner’s shop window.”

But are they truly cookies? The word cookie has been used to describe cakes, buns, and sweet wafers for only 300 years, and the gorgeous preserved pastries owned by the British Museum date back at least 1,300 years. But they’re eerily similar to modern cookies, especially the petal-shaped pastries that stood out so much to Stein. Well past stale at this point, they are very, very fragile, as a British Museum curator told Atlas Obscura back in 2019. Though they were once part of a traveling exhibition on Chinese culture, they aren’t often on display.

The pastries aren’t the only foods represented in the Astana cemetery. Ancient Gaochang mourners often sent their dead relatives on their final journeys well supplied with food for the afterlife. Research papers abound describing the pantry that was the tombs of Astana. Porridge, naan-like flatbreads, noodles, and the earliest Chinese dumplings ever found have all been recovered and studied for clues about life in the first millennium.

Many of the pastries unearthed in Astana’s tombs were made with wheat flour, while Stein observed dried-up grapes scattered alongside the sweets he found. Wheat and grapes have long had a foothold in the Turpan region. With its fields watered with well-maintained irrigation systems and a flourishing trade route passing through, the region was prosperous enough to develop beautiful sweets, pressed into molds to create elaborate designs or cooked into crispy lattice. As one research paper noted, “these food remains, particularly the elaborate cakes, reflect that diet was not just for food but also for a higher spiritual enjoyment for certain Turpan ancestors.”

But these cookies aren’t just for Turpan ancestors anymore. After seeing a photograph of the cookies on Twitter, Nadeem Ahmad set out to make them. Ahmad is the founder of Eran ud Turan, a living history group based out of the United Kingdom. The group focuses on early medieval Central Asia, particularly the 7th and 8th century. His special interest is the Sogdians, especially their vibrant art, lucious textiles, and feats on horseback.

While the realm of living history abounds with people recreating European and American eras, Ahmad is just one of four Sogdian reenactors. Ahmad says he has always been drawn to the era, especially because of the vivid artifacts left behind. “The paintings, the textiles, and the archeology is super colorful and it’s just super interesting,” he gushes.

Eran ud Turan holds the occasional costumed banquet, so Ahmad has recreated ancient dishes before. The Xinjiang pastries interested him due to the ancient Sogdian presence in Gaochang. He zeroed in on the petal-edged “jam tart,” and referred to The Chronology of Ancient Nations, a book from the year 1000, where historian Al-Biruni noted that Sogdians ate a pastry made of millet, sugar, and butter in the wintertime. “So I was like, well, I could make that into a cookie,” Ahmad says. He decided on grapes dabbed in apricot jelly for the filling, an appropriate choice seeing as the Turpan Basin is still famed for its grapes, while apricots hail from Central Asia and China.

It took five batches to get a good cookie. “Millet is a pain to work with,” he laments. But this adaptation of his recipe uses wheat flour, as the original cookies likely did, and makes a treat that looks surprisingly similar to the ones so preciously preserved in the British Museum. Don’t wait 1,300 years before eating them, though.

Ancient Jam Tartlets

Adapted from Eran ud Turan

Makes 22–24 cookies

Ingredients

1 stick softened butter

1 cup sugar

1 egg

2 cups flour

Purple, seedless grapes, either 12 large ones or 24 small ones

2 tablespoons apricot jam

Instructions

- Mix the softened butter with the sugar until pale, then add the egg and blend until completely incorporated.

- Gradually add in the flour, and mix well. The dough will be firm and a creamy yellow. Let it rest in the fridge for at least 30 minutes.

- Wash the grapes. If the grapes are very large, slice them into halves. To get one grape on each cookie, you’ll need about 24 grapes or grape halves. Gently mix with the apricot jam until they are completely coated.

- Take the cookie dough out of the fridge, and divide it into about two dozen pieces. Roll the pieces into balls, each about an inch in diameter.

- Preheat the oven to 350° F.

- After placing the balls on a greased or silicon pad–covered cookie sheet, gently score them crosswise four times, creating a pattern like an asterisk (*). Then, with your thumb, depress the center of each cookie so that the dough bulges outward.

- With a small spoon, scoop a grape or grape-half into each cavity, being sure to add a little of the jam as well.

- Bake the cookies for 12 to 15 minutes, or until golden along the edges and the top.