Keep These People Alive: David Grann on Killers of the Flower Moon

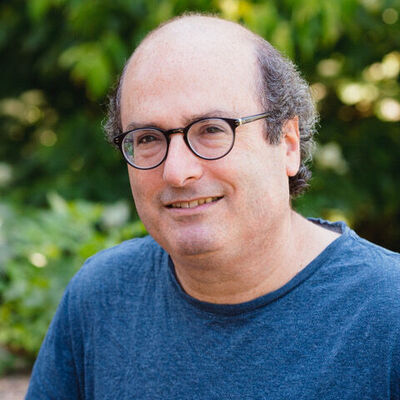

As the film world ardently awaits the opening of Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon,” which screened at the Cannes Film Festival, my anticipation is sky-high, as I’ve been following the film’s journey since 2017 upon Scorsese’s acquirement of the book rights to Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann. The article I wrote for Roger Ebert’s Women Writers Week in March 2023 centered on my journey with Scorsese’s film. Having read the source material twice, I began pondering the idea of interviewing the book’s author, David Grann. Many questions have churned in my mind about his why, his process, the struggles, the breakthrough moments, and how it felt to see characters from his book on the big screen. With fate on my side, I met Grann in my hometown of Naperville, IL, when he spoke at Andersons Bookshop in May this year. During my signing of his latest book, The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny, and Murder, he agreed to an interview.

David Grann is an investigative journalist, a hands-on truth-seeker, and a historian who cares about humanity. In some regard, he inhabits a modern-day “Indiana Jones'” lifestyle by searching the world for mysterious adventures that will enlighten readers as he “sets the record straight” with his discoveries. The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, and The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny, and Murder are based on research and his fervent digging for information. For example, in his physical trek into the Amazon jungle, searching for the lost city of Z, which he refers to as “a green hell,” he consulted with archeologists and brought forth new information. For Killers of the Flower Moon, he spent five years uncovering the systematic murders of wealthy Osage Nation people in the 1920s, traveling to various cities across the United States. However, Pawhuska, Oklahoma, is where his search began.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Who told you about the mysterious deaths of the Osage Nation, and what did they say that intrigued you to travel so far?

The historian is named John Fox [FBI historian in Washington DC], who had mentioned the case to me. With further research, I couldn’t find much about the Osage case, so I decided to take a trip to the Osage Museum in Oklahoma. I thought I might write an article as I was certainly interested.

I saw this great panoramic photograph on the wall of the Osage Museum, taken in 1924, and it shows members of the Osage Nation along with whites they are standing side by side, and it looked pretty innocent. I noticed that a portion of the photograph was missing. I asked the museum director, Kathryn Red Corn, why a portion of the photograph was missing. She said it was removed because it contained a figure that was so frightening. Then she pointed to the missing piece and said, “The devil was standing right there.” Next, we went into the museum’s basement, and she showed me an image of the missing panel. He’s peering out, very creepily from the corner; he was one of the main killers of many members of the Osage nation. He was the devil. I was always very haunted by that moment.

Most books don’t have a clear origin story. Killers of the Flower Moon is one of those rare cases in which there really was an origin story that was a very kind of “in that moment,” because I just kept thinking about that missing photograph. The Osage had removed it not to forget what had happened but because they couldn’t forget. So many people, including me, have never learned this history. We had not been taught it, and it has been effectively excised from our consciences.

Your research, both archival and tracking down the descendants of the murderers and the victims, seems like a daunting task. Is there a time when you had an “a-ha moment,” especially one that rang, “I’m on the right track”? I read about a guardianship ledger you found in Fort Worth, Texas. Can you talk about that?

When I began researching the story and the crimes, I thought the book would be about a singular evil figure, William K. Hale [Robert De Niro in the film], and that was the same theory the Bureau of Investigation, now known as the FBI, had with the case: that it was one key figure, a henchman who committed the crimes. Gradually, my discoveries chipped away at that theory of the crimes. One day, I visited a branch of the National Archives in Fort Worth, Texas, this enormous building that looked like something out of “Raiders of the Lost Ark” where they stored the last covenant. I pulled records on guardians and the “guardianships,” which was a very racist system in which the US government had appointed white guardians to manage the fortunes of members of the Osage nation.

I was trying to confirm a very simple fact: Did a certain Osage have a specific guardian? I wanted to confirm the names. In one of the boxes, I found a ledger that showed the guardians’ names and the Osages whose fortunes they had managed or, in many cases, stolen. The only other thing written in this ledger was one word, in addition to the guardian’s name and the Osages whose fortune they managed. An anonymous bureaucrat had written the word’ dead’ next to their name. Upon opening the book, I noticed a guardian who managed the fortunes of about five Osages; next to the first name, the word ‘dead’ was scribbled. I looked beneath it and saw the word ‘dead’ and then ‘dead’ again; ‘dead,’ ‘dead,’ ‘dead.” And I thought, wow, that’s just so strange. I saw many other Osages with the word ‘dead’ scribbled next to their name. One guardian had about a dozen Osages whose portraits they had managed and had nearly a 50% mortality rate. I assumed many deaths were natural causes, but they defied any natural death rate. The Osage weren’t starving; they were among the wealthiest people per capita in the world and had access to health care.

I began to look into some of these individual cases to see if I could find any evidence of malfeasance. Sure enough, in some cases, I found complaints that a guardian had stolen their money after the victims were found dead and that a relative complained of evidence that the person had been poisoned. I realized this seemingly anodyne book contained hints of this systematic murder campaign. These accounts demolished my original understanding of what the story was. That this was not a story about who did it or about a singular evil figure, it was much more a story about who didn’t do it. In other words, it was about a culture of complicity and a culture of killing. This also came from speaking to many members of the Osage Nation who shared with me suspicious deaths in their families that were never properly investigated.

The research really told me this was a deeper sense of the story in this history was that it was about a culture of complicity. It was about the guardians who were complicit. There were lawmen and a sheriff; there were prosecutors who were complicit, sometimes directly, in the murders or covering up the murders. Some morticians would cover up bullet wounds. Doctors had administered poisons; they were complicit in their silence.

I read you saw roadblocks in seeking a female’s point of view during the 1920s; that you noticed their voices were lacking in the files; they were often viewed as irrelevant and weren’t given a chance to speak or were ignored completely. I also found it interesting in your book when you compared the females’ notes or lack of them to the males and, during the 1920s, how they weren’t taken with much thought or respect. Can you talk about the notion of truth and finding the truth?

Mollie Burkhart [played by Lily Gladstone in the film] is the central figure in the book; in many ways, she is the heart and soul of the Osage history. Mollie, an Osage woman, was born in an Osage lodge practicing Osage traditions and speaking the Osage language. At a very young age, she was forcibly uprooted from her home and forced to attend a missionary Catholic boarding school. She’s no longer allowed to speak the Osage language there. They removed her blanket in a very brutal assimilation campaign. A few decades later, because of oil money under the land, she’s living in a large house. She’s married to a white settler, Ernest [Leonardo DiCaprio in the film]; in many ways, she is straddling not only two centuries but also two civilizations.

Mollie’s family begins to be targeted one by one. First, her older sister Anna [Cara Jade Myers] is shot. Then her younger sister Rita [JaNae Collins] suggests evidence that her mother is being poisoned. Rita is so terrified of these crimes; she moves closer to live near Mollie. At about 3:00 AM, Mollie hears a loud explosion in the middle of the night. Somebody planted a bomb underneath her younger sister’s house, killing her and her husband and a maid who was 18. All these deaths are going on around Mollie. She courageously crusades for justice, even though it’s putting a bullseye on her back.

Mollie goes to lawmen demanding they look into these cases. She hires private investigators who turn out to be corrupt. Often, because she’s Osage and because she’s a woman, her complaints and her cries are ignored by the white law enforcement establishment. It’s just one of the many examples where you can see this, and you can see this in the records. Even during the investigation, Mollie sometimes has to hit the law over the head to give her testimony. They often would not pay enough attention to her eyewitness testimony. It shows the deep prejudices at the time and why not only the Osage were being targeted, others were dehumanizing them, but also why these crimes went unsolved for so long.

I did speak this year with former Osage Chief Jim Gray; his great-grandfather, Henry Roan, was shot and killed in 1923. He said it was also the turning point of the FBI case. Can you speak about that?

Oh, yes. Jim’s a buddy of mine. The story of Henry Roan and how his life was just appallingly cut short is really important because he was another person forced to go to one of these boarding schools. He went to Carlisle, an abusive place towards Native Americans with a forcibly abusive acculturation process. Henry is murdered, at a young age, by William K. Hill, a very brutal crime. The death occurred on federal lands and Osage-allotted lands; the Justice Department had jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute that crime. Yes, it became pivotal because if it had been tried locally and not in a federal court, they would’ve been able to pack the jury, pay off the jury or buy off the prosecutor. Henry Roan’s case ultimately allowed some justice to come in some cases to at least have some criminals prosecuted.

What were some of the roadblocks in your research, whether it be interviewing or just the amount of archival research you had to complete?

When I originally saw that photograph in the museum, I didn’t think it would take me five years to research the book, but it did; it took half a decade to research and write as I tried to get every little bit of archival research. Mollie’s story was so important to me, and I wanted to anchor the book as much as possible in that Osage perspective. The book is told from her perspective as much as I could, which set me on the hunt for everything I could find. I found some letters between her and Ernest showing their relationship. I tracked down, and got to meet, Margie Burkhart, who is the granddaughter of Mollie.

Margie shared with me bits of family history, photographs, and what she knew about Mollie. It was speaking to people like Margie that really drove home to me as it did when I spoke to other Osage members; how much is this still living history? We are not talking about colonial times; we are talking about the 1920s; this was recent history. I’d say some of the biggest challenges I faced came from the fact that I began to realize there were many other suspicious deaths that had not been properly investigated by the Bureau of Investigation at the time, now known as the FBI. I looked into those cases, and sometimes, an Osage elder would give me documents that had been collected about a suspicious death in their family or murder in their family, hoping that maybe there’d be a way to resolve it or they’d always live with doubts about who exactly the perpetrator was.

One of the things I came smack into was the fact that these cases have not been properly investigated. The murderers are now dead, and so are the eyewitnesses. One of the great horrors was that the murderers had many cases, not only erased their victims, they had often erased their history too. And so, for me, the hardest was that in many of these cases, you can’t always shine a light. I had always thought the role of an investigative reporter or journalist is that when you’re doing work on genocidal crimes or social injustice, you’re trying to at least bring some sense of accountability. You’re trying to identify the perpetrators and record the voices of the victims, but in many cases, that’s not always possible. So, it was one of the real challenges, and in the end, I tried to make that horror one of the book’s central themes.

At times when I was reading the book, it was tough to read. I was wondering, for yourself, were there times when you had to stop for your mental and emotional health?

If you’re not human, you’re not affected. You are also writing about a story or a piece of history, and the goal is to record it. You almost want to be affected. One of the things I did, for example, was I began to collect photographs of the victims when I first began doing the book. I was in a different office, not this little one you’re seeing now; I started with some photographs of Mollie’s family members who had been murdered. But over time, I kept discovering more murder victims; first, a dozen, and then two dozen. Family members would give me photographs of those who have been slain and killed. And soon, I had an entire wall of photographs. So, every day, I continued to put them up, and I kept them in the office, and I walked by them, and I’d sit down. It was just a way to remind me of what this was about.

Why do you feel, despite the horrific content, that it is important for everyone to know what happened?

I really believe that the murderers and the system had tried consciously to erase this history in so many ways. The Osage nation is deeply, intimately familiar with their own history, as are others, but people outside the nation have erased this from our concept. I think it’s important to reckon it. But it’s less what I think than when I remember speaking to Osage elders, and many of them would invite me into their homes, and they would share with me bits of their history and their stories. Some said this explicitly, or it was implied that they thought it was important for the world to know and reckon with this past.

You can’t restore justice when there are these kinds of crimes you can’t bring back life. But hopefully, you can at least begin to restore a sense of the past. And in doing so, hopefully, learn something about the kind of people in the nation you want to be in the future. I also grew up with family members who were killed in the Holocaust, my grandmother used to tell me stories about people from her family, and she never said this explicitly. Still, the implication always was to keep these people alive. Keep these memories alive. Don’t forget.

Your parents are both very accomplished people. Your mother, Phyllis, CEO of a major publishing company, Penguin Putnam. And your father, Victor, an oncologist. What did you learn from them?

You know, I’m very blessed. I have great parents. My father sadly passed away a few years ago from Alzheimer’s. My mom is still here and in good health. My mom, in many ways, obviously being in the world of books and literature, sparked my earliest interest in reading and writing. I’m so grateful for her and for that. Although I always joke, she just gave me one piece of advice, and she said, “Whatever you do, don’t become a writer.” I think she thought it would be a difficult life. And so, like any good son, I decided to become a writer and prove her wrong. [laughs]

My dad was just a really gentle, sensitive soul. He also had this kind of voracious curiosity; and an unbelievable sense of decency about him. I think that came from caring for people, who had cancer, many of whom, especially in the period of time when he was a doctor, there weren’t always cures; there was a very high mortality rate, and so he was as much a rabbi as a doctor. Oh, and I often think of his sense of sensibility and sensitivity; I can’t say I have it, but I always aspire to it. [laughs]

During your time with him, what did you learn from Martin Scorsese?

First of all, he’s a brilliant man. He’s unbelievably curious; I was struck by his open curiosity to the world because I think that’s a certain kinship when you’re a reporter or a historian. It’s finding somebody who actually cares about this issue. I found that radiated from all the people around Marty, from the production team onward—that there was a fierce commitment to this story. And to me, that was very important.

How was it this last time walking out of the film, and what were you thinking?

Whether I see the movie or re-read the book, there’s an emotional power. I mean, there is unsettling to more unsettling, and to very unsettling. I mean, you don’t want that unsettling quality to go away. What’s always usual for me is that I spend most of my time with archival documents and records, and I don’t get involved much in the movie process. I just focus on my books and the history and let people who make movies make movies, and I work on my books. But there is something very unsettling, something powerful to see someone like, for example, Lily Gladstone, who plays Mollie Burkhart, with such emotional power. She’s just a remarkable actress. There’s just an enormous power about watching her bring Mollie to life.

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann is available now. The film opens on October 6, 2023.